Investigation summary

What happened

Portland Bay sailed from Port Kembla, New South Wales, on 3 July 2022 as bad weather was impacting its stay in port. It was expected to return when the weather improved. The ship then steamed and intermittently drifted about 12 nautical miles (miles) from the coastline.

In the early hours of 4 July, the main engine developed mechanical problems, which disabled the ship 12 miles from the lee shore. A couple of hours later, after unsuccessful attempts to resolve the engine problems, the ship’s master asked Australian authorities for tug assistance. About 2 hours later, a harbour tug from Sydney was en route but the ship had closed to one mile from the shore. The master made emergency use of both anchors to prevent stranding on the rocky shore about 12 miles south of Port Botany (Sydney) about one hour before the tug arrived to assist.

In the afternoon, 2 more harbour tugs arrived on scene and later began towing the ship away from the coast. A couple of hours later in the evening, one of the tugs’ towlines parted in the rough sea conditions. The ship then drifted towards the shore and the master again anchored about one mile from the shore off Bate Bay near Sydney. Later that night, the state’s nominated emergency towage vessel (ETV) deployed from Newcastle.

The ETV arrived on scene after midday on 5 July and connected a towline in preparation to tow the ship into Sydney. On the morning on 6 July, the ETV (with harbour tugs assisting) towed the ship into Port Botany, where it was berthed in the afternoon for refuge and subsequent repairs.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB investigation found that the ship had remained near the coast instead of safely clearing it in accordance with its safety management system (SMS) procedures. Operating its main engine at low speed while rolling and pitching heavily resulted in engine load fluctuating with turbocharger surge and non‑return flap hammering and distortion. Performance was further degraded by a leaky fuel injector, poor combustion and excessive cylinder lubrication resulting in sludge and deposits. When one of the 2 auxiliary blowers failed in the early hours of 4 July, air for fuel combustion significantly reduced and engine speed was limited to the minimum, effectively disabling the ship in bad weather.

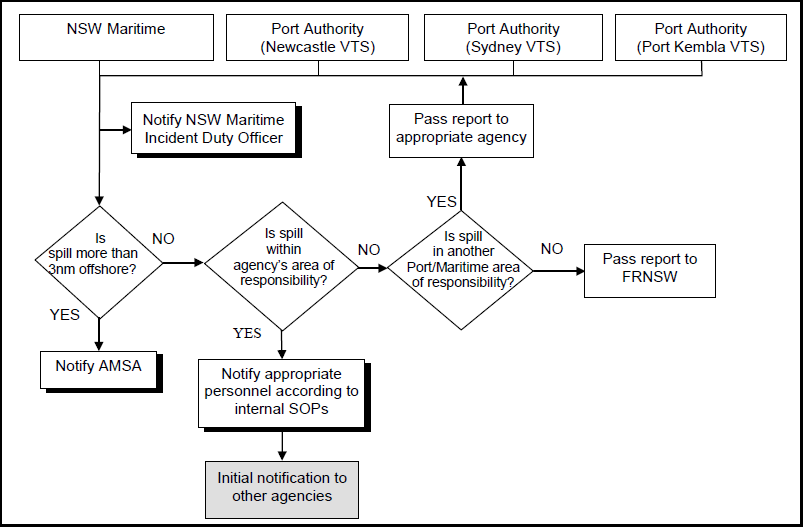

The investigation also identified that when the master reported the situation to the ship’s managers, Pacific Basin Shipping, it provided advice on engineering matters but not about notifying authorities as per the SMS procedures. This probably led the master to delay reporting to Port Kembla vessel traffic service (VTS) operated by the Port Authority of New South Wales (Port Authority). This delay was compounded when VTS did not promptly forward the master’s report to the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA). The various delays resulted in delaying the tug assistance requested and the master had to deploy both anchors to prevent stranding.

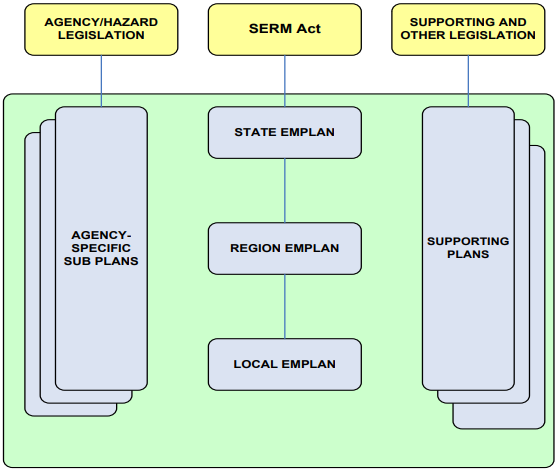

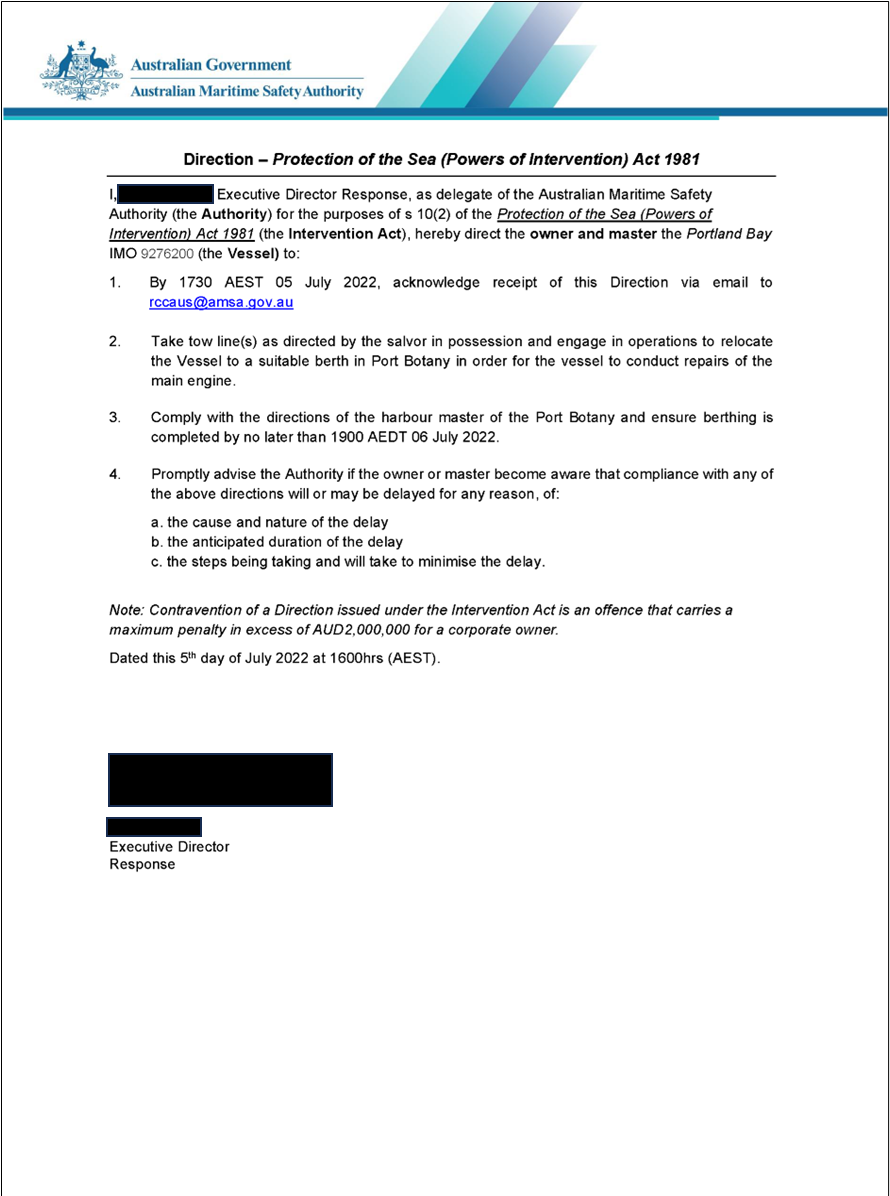

In addition, the investigation identified several safety issues associated with the emergency response. Specifically, AMSA procedures to comply with the National Plan for Maritime Environmental Emergencies (National Plan) were not effectively implemented. Similarly, the Port Authority’s procedures to comply with the NSW Coastal Waters Marine Pollution Plan (NSW Plan) and its Port Safety Operating License (PSOL) were not effectively implemented. Further, the coordination of critical elements of the emergency response, including emergency towage, salvage and refuge, between the Port Authority, Transport for NSW (NSW Maritime) and AMSA with their respective roles and responsibilities was inadequate and inconsistent with National Plan principles. These safety issues prolonged the emergency and the exposure to stranding, with potentially severe consequences.

The ATSB also found that the AMSA process to issue directions was inefficient and resulted in excessive time to issue directions to enable Portland Bay to enter Port Botany for shelter. While this delay did not further prolong the emergency, such delays increase risk in time‑critical situations. The investigation also found that United Salvage, the salvor, was severely limited in its ability to provide the salvage services required as it did not own or operate any towage vessels so was reliant on towage providers. This limitation was not made clearly known to the ship’s master, owners or managers or the involved agencies to allow them to properly assess whether the most suitable towage vessels, including the ETV, had also been promptly deployed.

A key finding was that the ship’s anchors prevented a catastrophic stranding on the rocky shore in heavy weather, noting that they were not designed for such use but can be used as a last resort in emergencies.

What has been done as a result

Pacific Basin Shipping has revised its SMS crisis management procedures to include at least one exercise each year outside of office hours and conducted 2 such drills since the incident. A fleet‑wide circular emphasising the importance of early reporting to authorities to shipboard staff and office‑based teams was disseminated. In addition, the company produced a case study training video for seafarer training and office‑based teams to enhance emergency response as per its procedures with an emphasis on early reporting to authorities. The ATSB has assessed the safety action as having adequately addressed the safety issue regarding the late reporting of the incident.

While AMSA only partially agreed with the safety issue about response coordination and did not agree with the 3 other safety issues addressed to it, a range of relevant safety action has been taken. This included a review of its procedures, fortnightly incident escalation exercises, review of emergency towage capability, review of emergency coordination arrangements, increased resourcing (staff) and training and a comprehensive review of the National Plan. The ATSB welcomes this action but has recommended that AMSA takes further necessary action to adequately address all 4 safety issues.

The Port Authority advised that as the incident did not involve a spill (pollution), its role as the state’s combat agency was not ‘enlivened’. It added that AMSA and NSW Maritime had roles and responsibilities for this incident. The Port Authority did not advise of any safety action, hence the ATSB has recommended that it take action to address both safety issues addressed to it.

Transport for NSW (NSW Maritime) advised that it had taken action to improve response coordination with the Port Authority, which included discussions and joint exercises. However, given the Port Authority’s response and lack of safety action, the ATSB considers it important that NSW Maritime takes safety action to adequately address the safety issue concerning response coordination and has issued a recommendation accordingly.

Finally, the ATSB has recommended that United Salvage takes action to address the safety issue with respect to clearly informing the master, owners or managers of the ship to be salved of the salvor’s capabilities and limitations in performing the salvage services required.

Although no safety issue was addressed to Svitzer Australia, it has upgraded the towing equipment of its Sydney‑based harbour tug that assisted with the response.

Safety message

Portland Bay’s near stranding provides invaluable lessons on managing emergencies to avoid severe consequences. Optimal emergency management relies on taking a series of appropriate actions in a timely manner, which often determine the degree of success of the response. Failure is usually associated with actions that are ‘too little, too late’. Australia’s National Plan reiterates the principle of over‑escalation in an initial response as it is more effective to scale down than up.

Effective emergency response plans and procedures do not leave outcomes to good fortune, which on rare occasions have contributed to a positive outcome. The National Plan principles and arrangements provided the best available options to manage risks along Australia’s extensive and pristine coastline, which also has inherently limited emergency response resources.

The occurrence

Overview

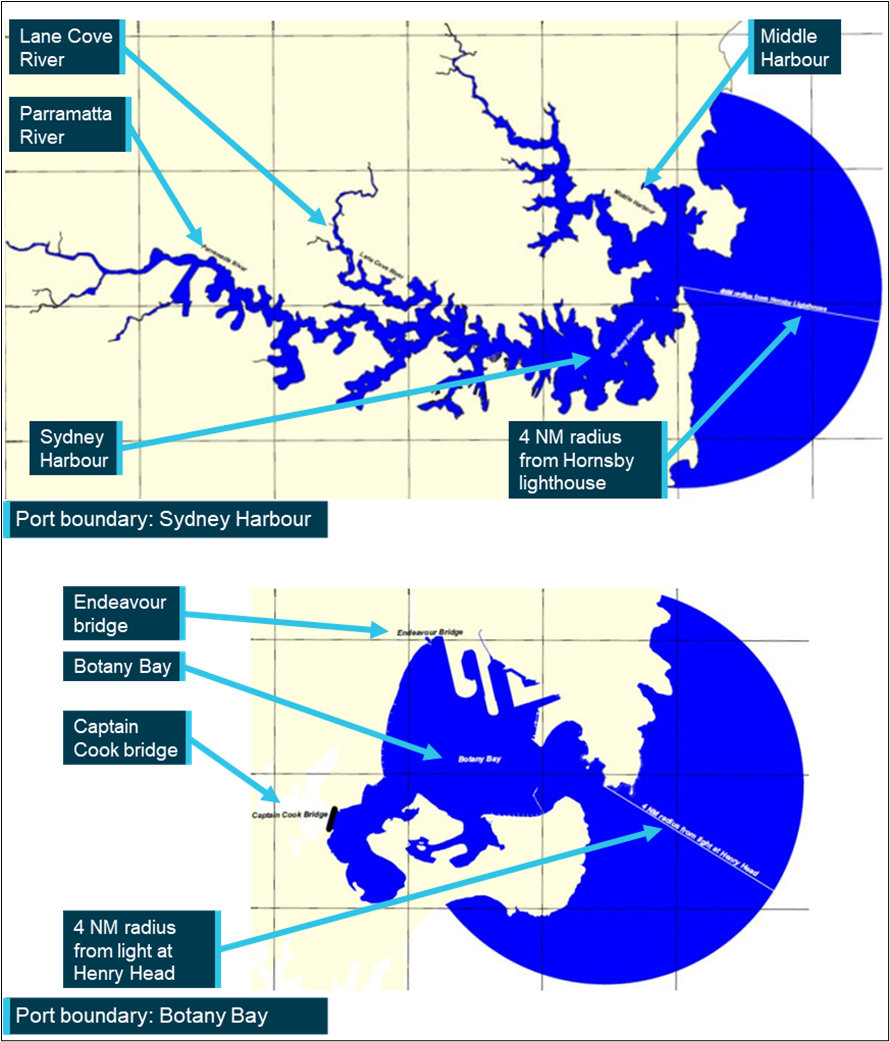

On 3 July 2022, adverse weather that was forecast to further deteriorate had made it unsafe for the bulk carrier Portland Bay (cover) to remain berthed in Port Kembla, New South Wales (Figure 1). Consequently, the decision was made for the ship to leave the port and remain at sea until the weather improved sufficiently to allow a safe return.

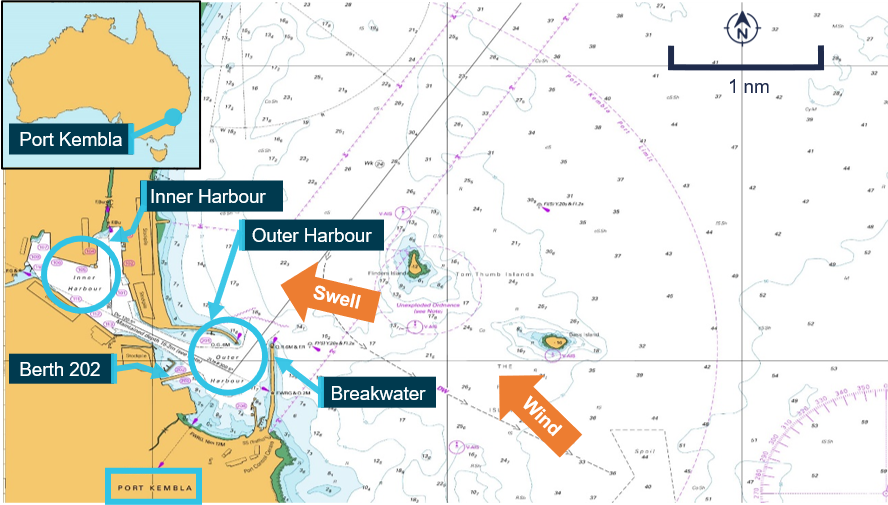

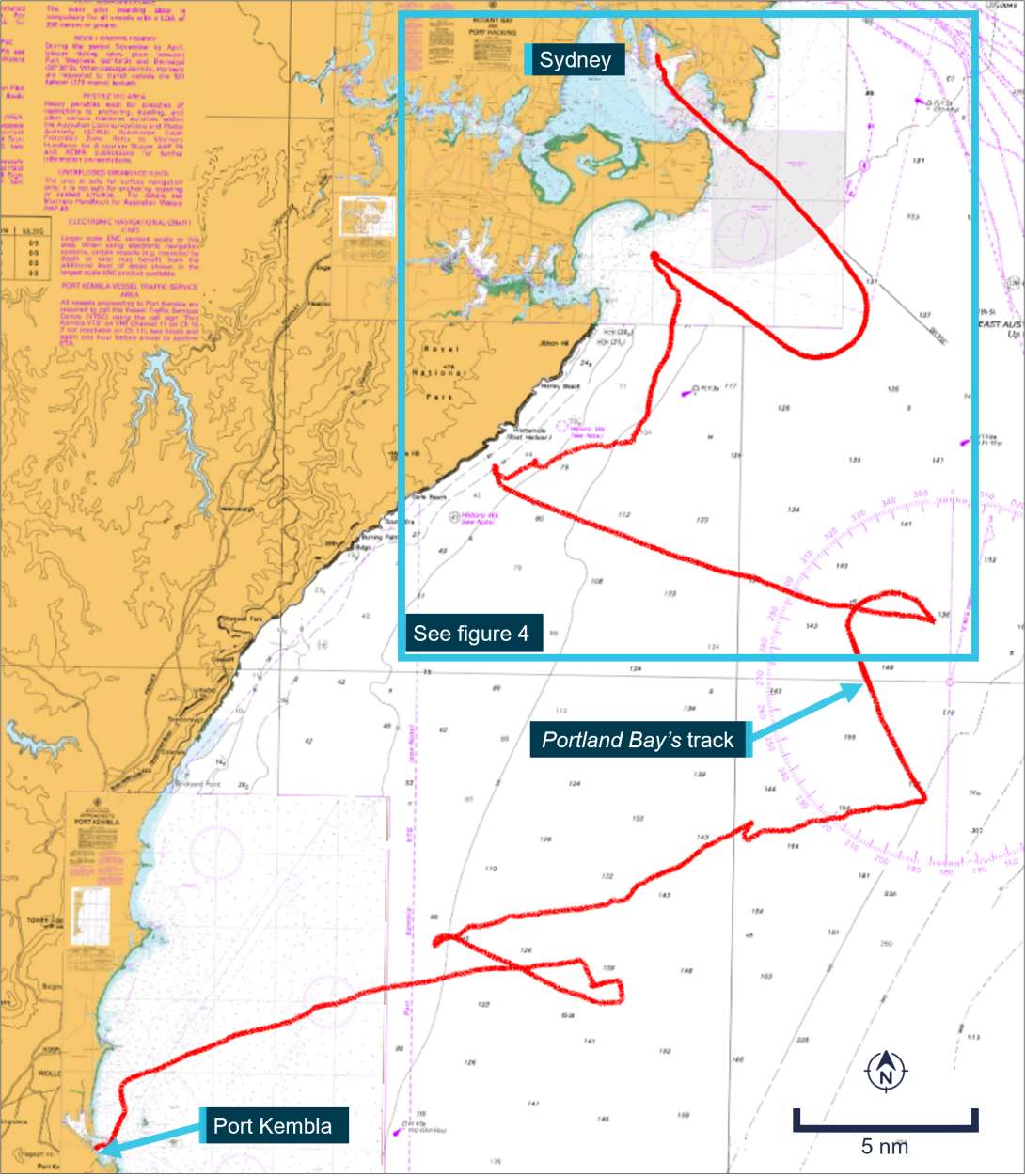

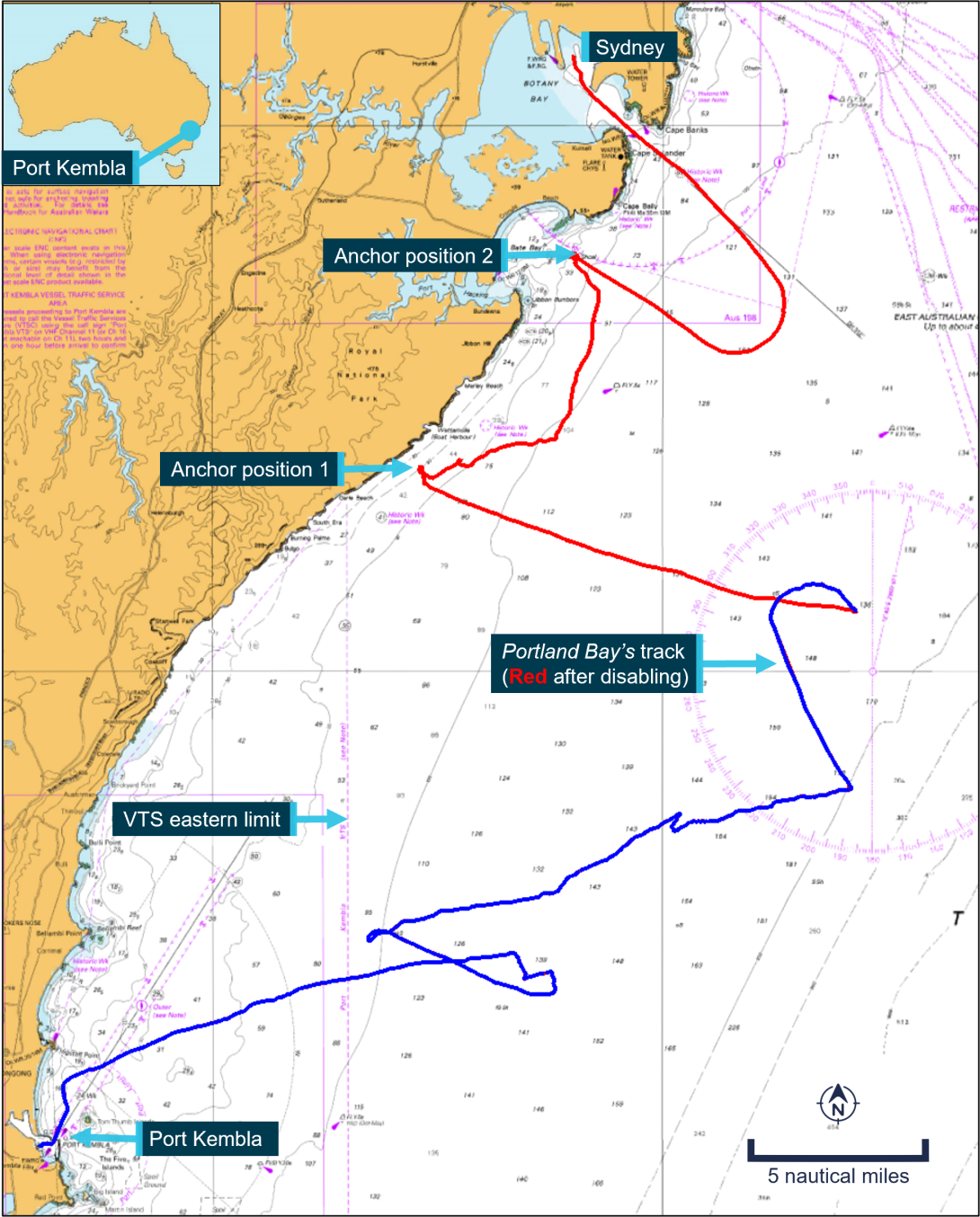

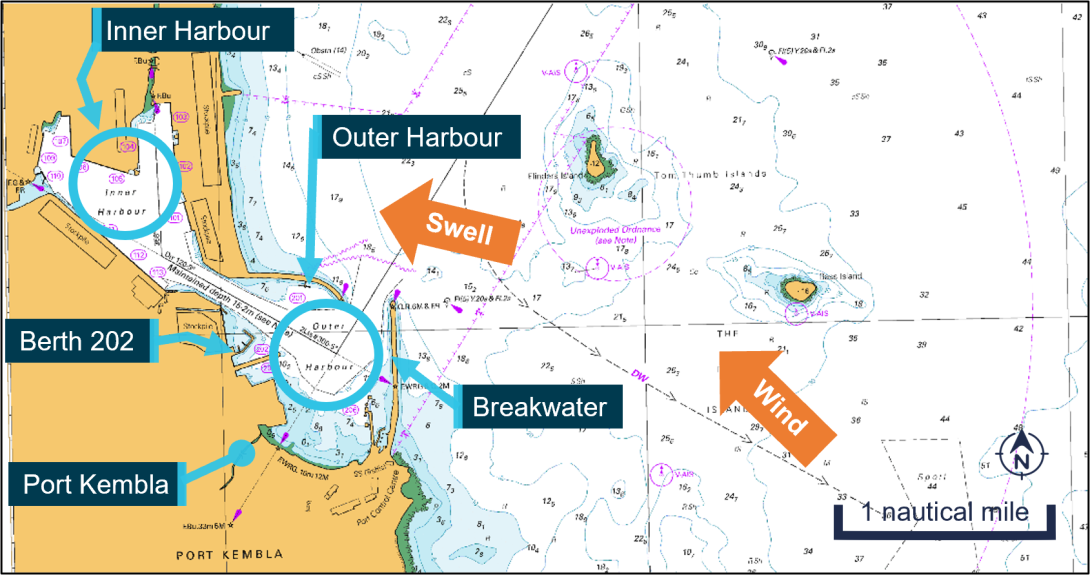

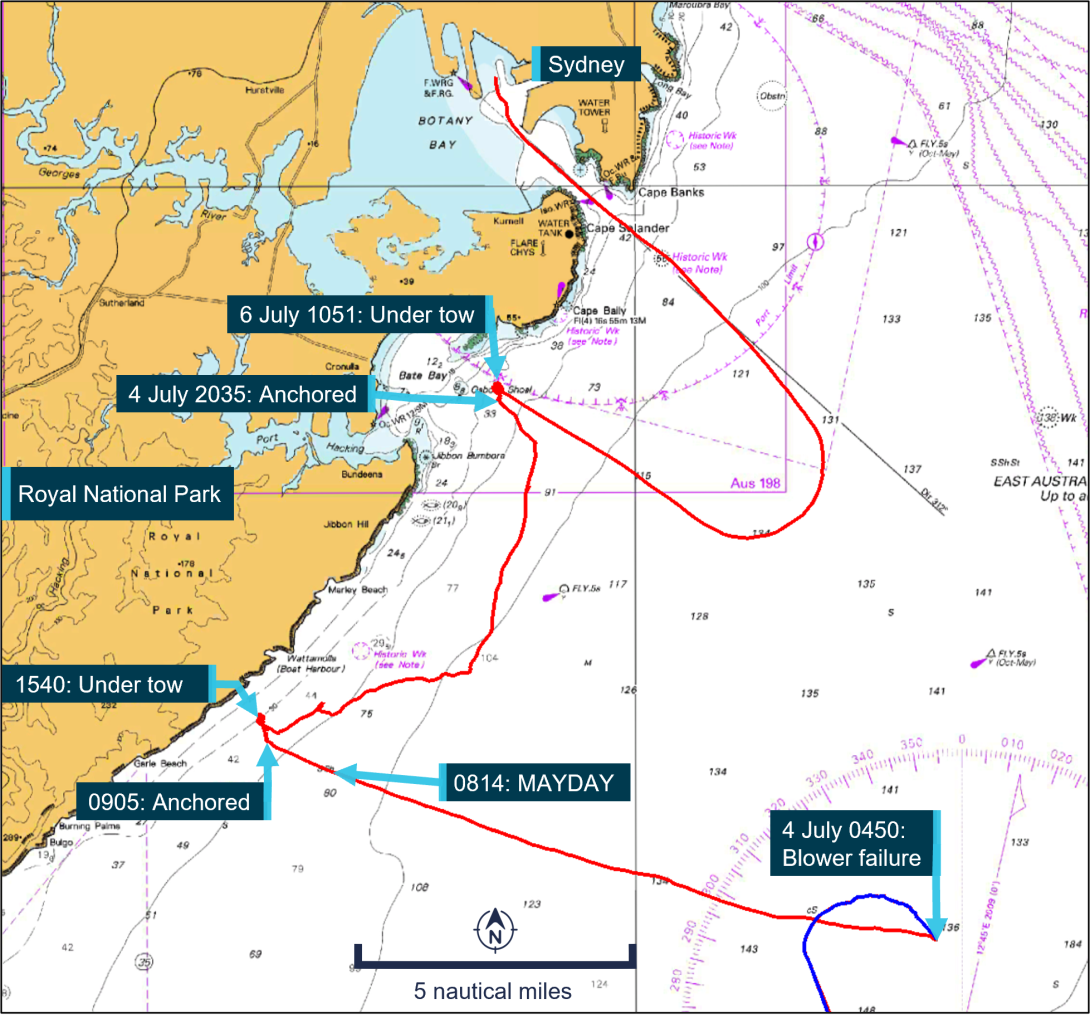

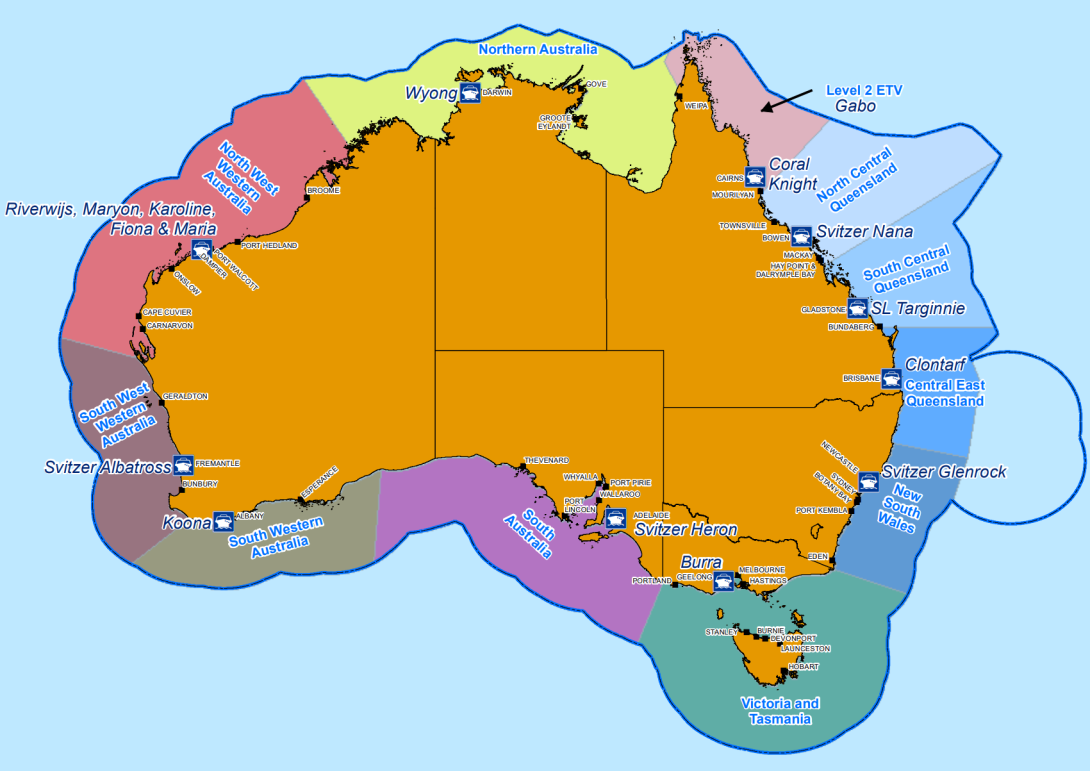

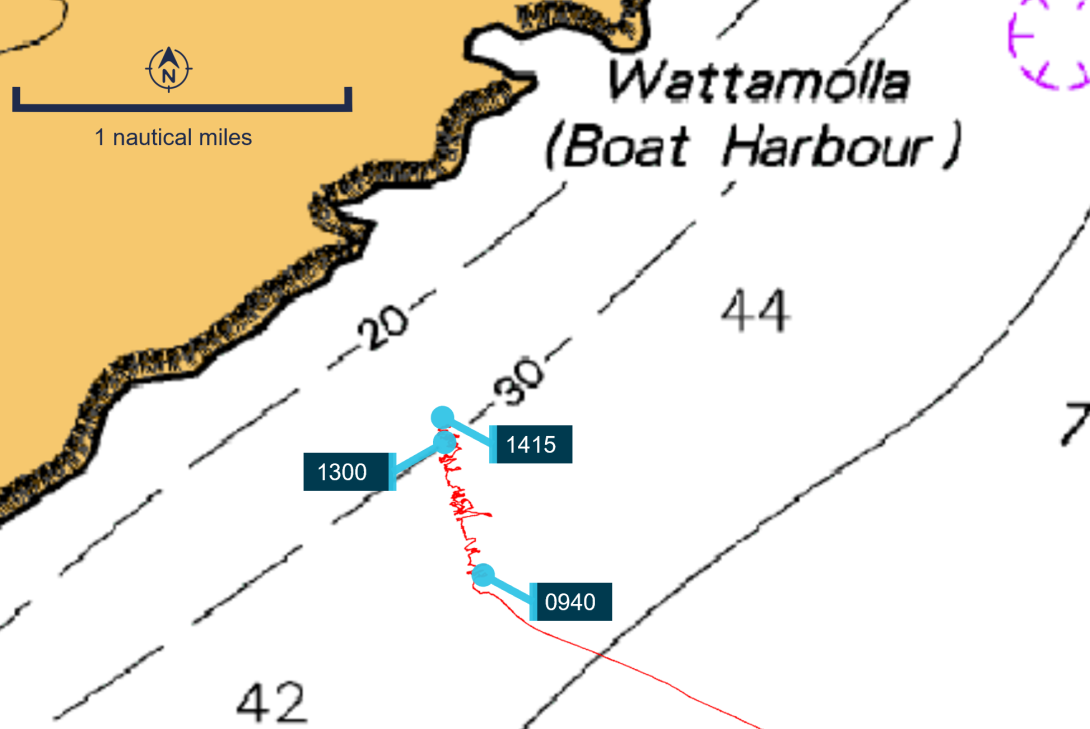

Figure 1: Portland Bay’s movements from 3 to 6 July 2022

Source: Australian Hydrographic Office and Portland Bay’s recorded voyage data, annotated by the ATSB

Portland Bay departed the port in the afternoon and steamed on an east‑north‑easterly course until that evening when it was about 12 nautical miles (miles) from the coastline where its main engine was stopped. The ship drifted towards the coast in the south‑easterly winds and seas and the engine was used intermittently that evening and night to avoid getting closer to the coast.

Shortly before 0500 local time on 4 July, the main engine developed mechanical problems, which limited the engine speed to dead slow ahead (the minimum). The problems could not be resolved, resulting in Portland Bay being effectively disabled about 12 miles from a lee shore. In the prevailing conditions, the ship began drifting at a rate of 2–3 knots[1] towards the coast.

Two hours later, at 0657, after attempts to resolve the engine problems were unsuccessful, the ship’s master notified Port Kembla vessel traffic service that the ship’s main engine had failed and requested tug assistance. At 0848, a harbour tug from Sydney[2] left the port for the ship’s location, which was then about 1.5 miles from the coastline about 22 km south of Sydney.

At 0905, when about one mile from the shore, the master deployed the ship’s anchors to prevent stranding on the rocky coastline of Royal National Park (Figure 1, Anchor position 1). Subsequently, unsuccessful attempts were made to evacuate the crew by helicopter.

At 1010, the tug arrived off the ship and, about 4 hours later, 2 other Sydney harbour tugs arrived. By late afternoon, these 2 tugs began towing the ship away from the coast. However, a couple of hours later, one of the tugs parted its towline and the ship again began drifting towards the shore.

At 2035, the ship was anchored about one mile from the shore to prevent stranding in Bate Bay near Sydney (Figure 1, Anchor position 2). Both tugs, one with its towline connected, remained with the ship. Later that night, the nominated emergency towage vessel (ETV) for New South Wales was deployed from Newcastle (about 90 miles north of Bate Bay) to tow the ship to safety.

On 5 July, at about 1300, the ETV arrived off Bate Bay and later connected a towline while plans to tow the ship into Sydney (Port Botany) in daylight on the following day were finalised. The harbour tug with a towline connected remained with the ship.

On 6 July, at about 1100, the ETV and 2 harbour tugs began towing Portland Bay to shelter in Port Botany (Figure 2). By late afternoon, the ship had been safely berthed in the port. Over the following week, the main engine was repaired to make the ship seaworthy.

Figure 2: Portland Bay under tow on 6 July

Source: Port Authority of New South Wales

The following sections outline key events preceding the incident and greater detail of the numerous events that occurred over the course of the incident between 4 and 6 July.

The incident

Background

Portland Bay arrived and anchored off Port Kembla on 19 June 2022, following a voyage from Susaki, Japan, loaded with a cargo of cement. On 21 June, the ship was conducted by a harbour pilot into the port’s inner harbour and, at 1724 local time, secured at berth number 104.

Cargo unloading began that evening, and 8 new crew members, including the relieving master and chief engineer, joined the ship. On 22 June, another 5 relieving crew members joined the ship. The new chief engineer intended to complete several items of main engine maintenance, including a few that had been pending for some time, during the ship’s stay in port.

While unloading cargo between 22 and 26 June, the master obtained permission from the Port Kembla harbour master to immobilise the main engine, from time to time, allowing the engineers to clean the charge air cooler, lubricating oil (LO) cooler and LO filters. When unloading was completed in the evening on 26 June, some maintenance items remained.

On 27 June, Portland Bay departed for sea to clean its cargo holds for the next cargo. The crew was to clean accessible areas of the cargo holds before berthing in Port Kembla on 2 July, where shore labour would clean the upper parts of the holds. The ship anchored or drifted off the port while the holds were cleaned.

On 1 July, the ship’s agent in Port Kembla, Monson Agencies Australia (Monson), advised Pacific Basin Shipping (Pacific Basin), the ship’s Hong Kong‑based management company, of likely disruptions to hold cleaning due to heavy rain and a large north‑easterly swell forecast for 3 and 4 July. Monson advised that the ship might be required to leave port to avoid damage to the berth and ship due to the heavy swell. Pacific Basin decided to continue with the scheduled berthing.

At 0154 on 2 July, Portland Bay was secured starboard side alongside berth number 202 in the outer harbour (Figure 3). At 0410, the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) issued a forecast for gale force winds up to 35 knots and an easterly swell of 3 to 4 m for the seas off the port on 3 July. At 0500, entries in the ship’s logbook indicated easterly winds at ‘force’[3] 3 (7–10 knots).

Figure 3: Location of berth 202 (wind and swell direction at 1100 on 3 July)

Source: Australian Hydrographic Office, annotated by the ATSB

As forecast, the weather continued worsening and, at 1600, southerly winds at force 6 (22–27 knots) were recorded in the logbook. At 2243, Monson advised the master via email that Port Kembla vessel traffic service (VTS) [4] had issued additional harbour master’s instructions due to worsening weather. They included running additional mooring lines and lowering the outboard anchor to the seabed. In addition, VTS advised that the anchorage was closed and ships drifting off the port were to keep ‘at a safe distance (around 12 miles)’. The anchorage and VTS area were shown on navigational charts.

The charted limits of the VTS area showed its eastern limit lay along longitude 151°04.5’ E and extended south from Garie Beach (about 19 miles north of the port entrance) to a southern limit along latitude 34°30.4’ S, which passed through Perkins Beach south of the port (Figure 1). The line of the eastern limit line passed 8.5 miles east of the port entrance and nautical publications described the ‘VTS area, VTS limit/reporting line or VTS area reporting line’ and detailed requirements to report to VTS when passing a reporting line.[5]

On the morning of 3 July, Portland Bay began to be affected by the swell at its berth in the outer harbour. At 1027, the terminal manager contacted VTS and requested that the duty pilot assess whether it was safe for the ship to remain at the berth in the worsening weather and swell. At 1035, the master requested and received permission from VTS to lower the port anchor to the seabed.

At about 1050, after a risk assessment by the duty pilot and the harbour master, VTS asked the master to prepare to depart the port to avoid damage to the wharf and ship due to its movement in the swell. The master agreed with the assessment and began preparing for departure. The pre‑departure checks included testing the main engine (ahead and astern propulsion) and steering gear. A south‑easterly wind at force 6 (22–27 knots) was recorded in the logbook at the time.

At 1235, a harbour pilot boarded Portland Bay, conducted a master‑pilot information exchange and confirmed pre‑departure checks had been completed. The ship had maximum water ballast on board, forward and aft draughts of 4.11 m and 5.30 m, respectively (the propeller was fully immersed at an aft draught of 5.1 m) and a displacement of approximately 15,500 tonnes.[6]

At 1300, all was in readiness to depart and, at 1312, the ship was manoeuvred clear of the berth with 2 tugs assisting. By 1334, the ship had cleared the port’s entrance and the pilot disembarked.

Propulsion failure

After disembarking the pilot, Portland Bay’s master set an east‑north‑easterly course with the main engine at manoeuvring full ahead speed (90 rpm). In the prevailing heavy weather, the engine remained on standby with the engine room manned (the ship was equipped to operate with unattended machinery spaces – UMS). The mates were on usual bridge watches and the master attended periodically. The ship experienced moderate to heavy rolling and pitching and the master recalled having difficulty maintaining a steady course and achieving a speed[7] of 2–3 knots.

At 1800 on 3 July, when the ship was 14 miles east‑north‑east of Port Kembla, the master stopped the main engine and the ship began drifting about 12 miles off the coastline. A south‑easterly wind at force 7 to 8 was recorded in the logbook. The ship was rolling and pitching heavily at times and was drifting in a westerly direction towards the coast at about 3 knots.

At 1937, when the ship was about 8 miles off the coast, the engine was restarted and speed gradually increased to manoeuvring full ahead to again steam on an east‑north‑east course. At midnight, east‑south‑easterly winds at force 7 (28–33 knots or near gale force) were recorded in the logbook. The third mate handed over the navigational watch to the second mate, conducted routine fire and safety rounds[8] and reported nothing untoward.

At 0200 on 4 July, when the ship was 15 miles from the coast (24 miles east‑north‑east of Port Kembla), the engine was stopped. The south‑easterly wind had moderated to force 5 (17–21 knots) but the heavy swell from the gale force winds earlier persisted. At 0330, the ship surged[9] and rolled heavily. Soon after, the second mate put the engine dead slow ahead (42 rpm), the minimum speed. The master came up to the bridge and, at 0337, the engine order was increased to half ahead (80 rpm). At 0344, the master ordered full ahead and a heading[10] of 110° to steam away from the coast (which at that stage was about 10 miles off) before returning to his cabin.

At 0400, when the second mate handed over the watch to the chief mate, a south‑easterly wind at force 6 to 7 was recorded in the logbook. The second mate then completed fire and safety rounds and recorded nothing unusual. During those early hours of the morning, the BoM wave rider buoy off Sydney recorded waves with a ‘significant wave height’ of 5.04 m and a ‘maximum wave height’ of 8.44 m from the east‑south‑east.[11]

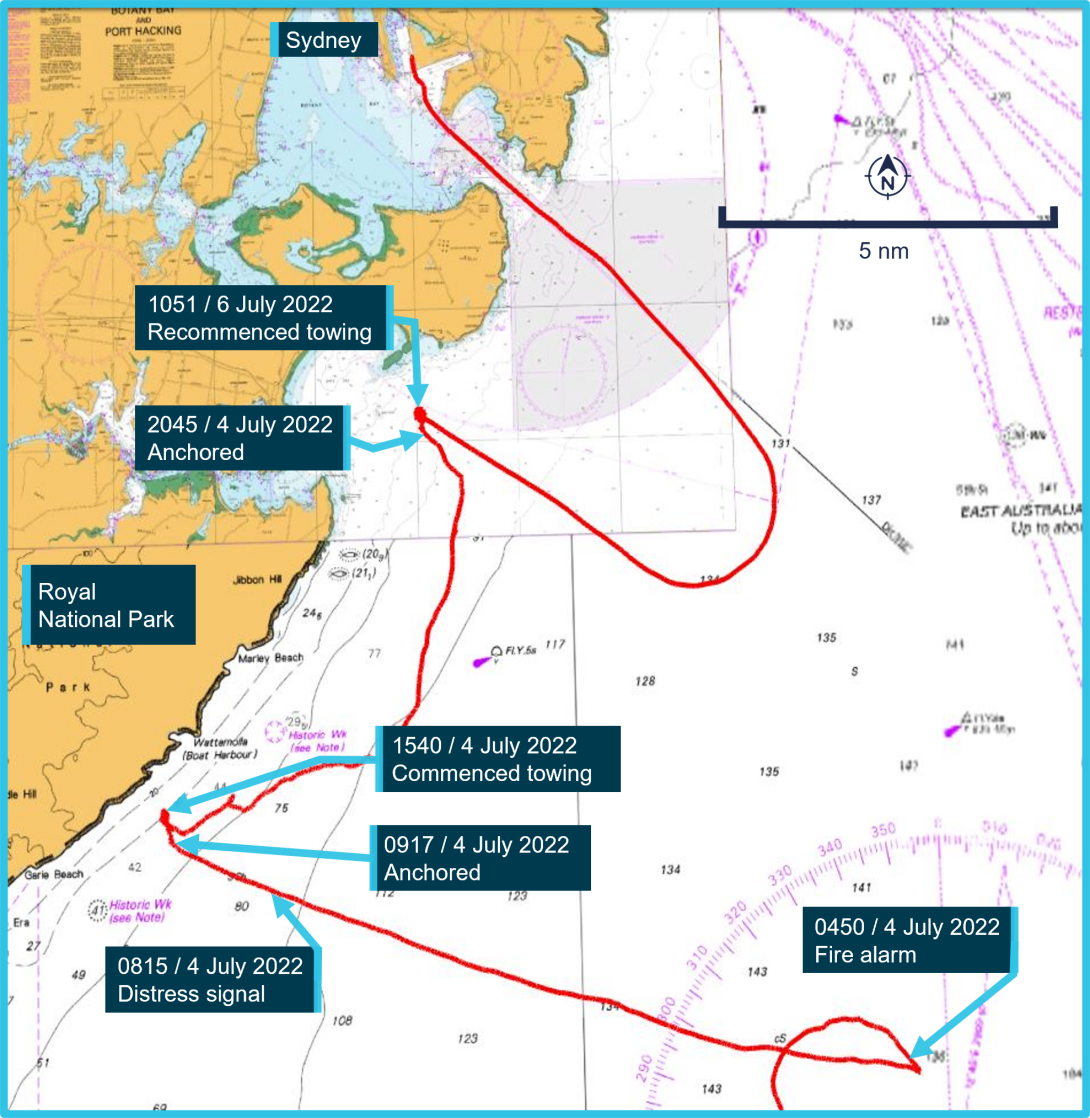

At 0450, when Portland Bay was about 12 miles from the coast, an alarm on the bridge fire alarm panel alerted the chief mate to 2 fire detectors in the lower, starboard side of the engine room that had been activated (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Time and location of key events during the incident

Source: Australian Hydrographic Office and Portland Bay’s recorded voyage data, annotated by the ATSB

The second engineer, on watch in the engine control room, and the chief engineer (also in the control room) investigated and found smoke and a burning smell coming from main engine auxiliary blower number 2 (see the section titled Auxiliary blower number 2 under Propulsion). At about 0451, the second engineer returned to the control room, stopped the blower and called the bridge for engine speed to be reduced. The chief mate reduced speed and called the master. At 0453, when the master arrived on the bridge, the speed order was slow ahead (58 rpm).

By 0507, the engine speed had been reduced to dead slow ahead. On the ship’s south‑westerly heading, the wind was on the port beam and pushing it towards the coast. At 0513, the master ordered slow ahead but engine speed remained about 42 rpm (dead slow ahead). The master then ordered a course change to an easterly heading and pointed out to the chief mate that the ship was 3 or 4 hours away from (drifting onto) the coast about 11 miles off.

Ship disabled

At 0519 on 4 July, the master asked the chief mate to get an update from the engine room and was advised that the chief engineer was coming up to the bridge. When the chief engineer arrived at 0522, the master stated that they had one hour to make repairs otherwise tugs would need to be called. The chief engineer advised that the blower could not be repaired in one hour and gave reasons for that assessment. When the master asked if the engine could be run at full ahead, the chief engineer advised that it was not possible due to the active engine alarms and limits.

At 0523, the master asked the chief engineer to call Portland Bay’s dedicated manager (in Pacific Basin’s office) and explain that it was ‘really dangerous’ if the speed could not be increased as the ship was drifting towards the coast (less than 11 miles off) at 3.5 knots. Subsequent attempts to call the ship’s manager via satellite telephone were unsuccessful as the manager was travelling.

At 0533, the chief engineer instead called Pacific Basin’s marine and safety manager (marine manager) and explained the situation. Meanwhile, to help turn the ship on to an easterly heading, the master had unsuccessfully tried increasing engine speed. At 0539, the master (who had joined the call to respond to the marine manager’s questions) advised that it was not possible to steam 50 miles away from the coast as engine speed was limited to dead slow ahead.

Soon after, at 0541, the marine manager called the fleet manager and explained the ship’s situation. Two minutes later, the fleet manager called the ship and suggested that the chief engineer override the engine torque limiter and active alarms to increase speed. While the chief engineer went to the engine room to do so, the master tried turning the ship to an easterly heading away from the coast, now less than 10 miles off. The master voiced concerns to the chief mate a few times about the rate at which the ship was closing the coast.

At 0555, after unsuccessful attempts to increase engine speed, the master asked the chief engineer to come to the bridge and call the fleet manager. From about 0600, the chief engineer discussed options with the fleet manager. When the call ended at 0606, the master told the chief engineer and chief mate that if speed could not be increased and no one helped, they would be on the ‘rock’ in the next hour.

Meanwhile ashore, at about 0615, the marine manager had called Pacific Basin’s designated person ashore (DPA)[12] and provided an appraisal of the ship’s situation.

At 0624, after the engine stopped and could not be restarted, the master ordered ‘not under command’ (NUC)[13] signals be displayed and the disabled ship’s status on the ‘automatic identification system’ (AIS)[14] be set to NUC.

At 0627, the chief engineer updated the fleet manager and was asked to start the engine from the local emergency controls (adjacent to the engine) and increase rpm until the turbocharger became effective (see the section titled Engine combustion air system under Propulsion). At 0631, the master, having asked the chief engineer how long it would take to try the local controls, agreed to trying to start the engine. The master also noted that there was little available time remaining to obtain tug assistance.

At 0634, when the chief engineer started the engine from the local controls, the rpm would not increase beyond about 42 rpm (dead slow ahead). At 0640, the master took the fleet manager’s call and advised that the engine speed had not increased beyond 27 rpm. They discussed the situation for 6 minutes before the master concluded the call, advising that the chief engineer would provide an update shortly. The master then asked the chief mate to check the ship’s emergency procedures for contacts in the Sydney area.

At 0650, the master called the fleet manager and discussed requesting assistance from local authorities. The chief engineer also arrived on the bridge, provided the fleet manager an update and was asked to again try increasing speed to full ahead from the local controls.

At 0655, after the chief engineer’s attempts to increase speed had again been unsuccessful, the master instructed the chief mate to call ‘Marine Rescue Sydney’. At that time, the disabled ship was less than 7 miles from the coast.

Meanwhile, at 0656, Pacific Basin’s management team established a virtual communications group to manage the emergency. The group comprised the marine and safety manager, fleet manager, fleet director and DPA (references to Pacific Basin hereafter mean this group or the company in general).

Tugs called

At 0656 on 4 July, the chief mate called ‘Marine Rescue Sydney’ on very high frequency (VHF) radio channel 16 but received no response. At 0657, the chief mate called Port Kembla VTS and advised that Portland Bay's main engine had failed, that it was drifting towards the coast and required tug assistance. Port Kembla VTS suggested anchoring the ship, which the master ruled out due to the deep water in the ship’s location (see the section titled Bridge procedures under Safety management system).

At 0659, Port Kembla VTS informed the ships’ agent in Port Kembla, Monson, that the ship’s master had asked for tug assistance. The VTS then notified personnel within the Port Authority of New South Wales (Port Authority) of the ship’s situation.

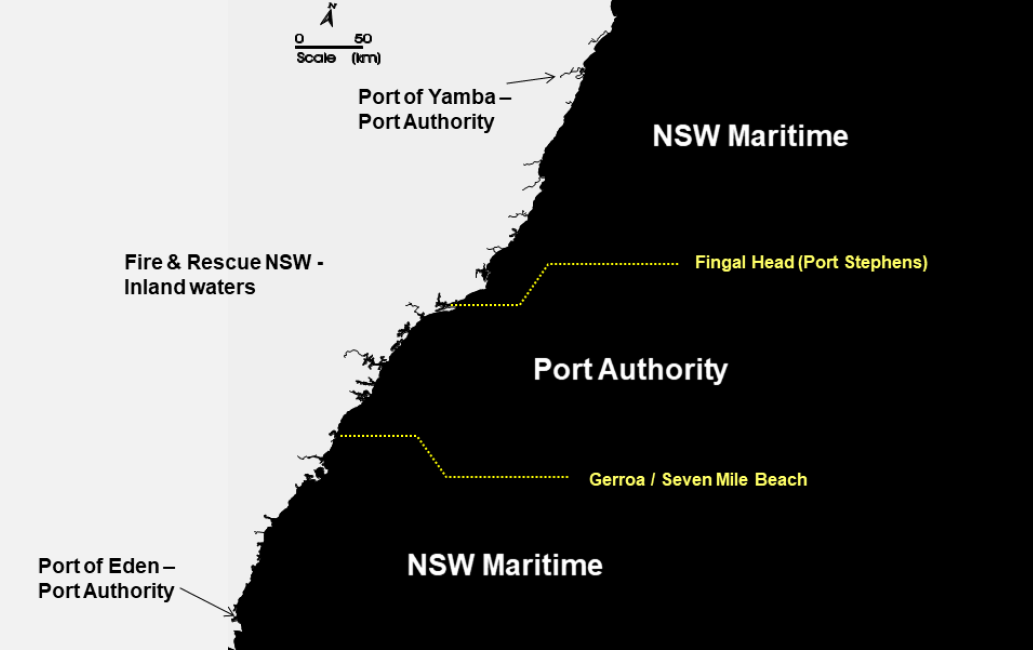

Meanwhile, the master and chief mate discussed whether ‘RCC’[15] should be contacted as no response had been received from ‘Marine Rescue Sydney’. Instead, at 0703, the chief mate called ‘Marine Rescue Port Kembla’ (Marine Rescue) and was advised that relevant authorities would be notified of the situation and to await an update. The ship was about 6 miles from the coast and drifting towards the 3‑mile limit of New South Wales coastal waters (see the section titled Legislation and plans under State level).

While awaiting an update from Marine Rescue,[16] the master and chief mate discussed whether to broadcast an urgency (PAN)[17] or a distress (MAYDAY)[18] message. At 0709, the chief mate informed Marine Rescue that the ship was 1.5 hours away from the ‘shore’ and was advised that Marine Area Command (MAC)[19] and Sydney Water Police had been notified. Marine Rescue also suggested broadcasting a PAN message. Noting this advice, the master told the chief mate that, at the ship’s drift rate of more than 4 knots, it would ground in 1.5 hours.

Ongoing communications with Pacific Basin had continued intermittently and, at 0714, the master advised that the ship was 2 hours from the coast and Australian authorities had been requested to provide tug assistance. At 0716, the chief mate broadcast a PAN message requesting assistance on VHF channel 16, which Marine Rescue acknowledged. At that time, the ship was 5.8 miles from the coast (about 11 miles south of Port Botany).

At about this time, the responsible NSW Maritime manager[20] called the joint rescue coordination centre (JRCC) operated by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA)[21], after being earlier alerted by an officer in NSW Maritime’s Port Kembla office who had been advised by Marine Rescue that Portland Bay was drifting off the coast. The manager reported that JRCC ‘was not aware of the incident’.

At 0719, Pacific Basin asked the master to prepare for emergency anchoring while waiting for tug assistance. At the same time, Sydney VTS (which had heard Portland Bay's PAN broadcast) started monitoring the ship’s movement on its electronic displays.

A few minutes later, at 0725, Sydney VTS requested Svitzer Australia (Svitzer), the port’s main towage provider, for ‘emergency tug’ availability (see the section titled Towage licence system under State level). Sydney VTS then asked Port Kembla VTS which emergency services had been notified or activated.

Meanwhile on board, at 0727, the master ordered the second and third mates to report to the bridge wearing working clothes and safety boots. A minute later, when Marine Rescue asked for the ship to be anchored, the master once again advised that anchoring was not possible in the deep water. The master asked if a tug could reach the ship in one hour and was advised that an estimated time of arrival (ETA) would be provided when available.

Sydney VTS followed up Svitzer for an available tug at 0731, and again at 0739, but no tug response time was provided. At 0740, Sydney VTS contacted the port’s other towage provider, Engage Towage, and was advised that a tug would be immediately prepared to deploy.

Meanwhile on board, communications with Pacific Basin had continued with the chief engineer advising that the damaged blower could only be repaired when the engine was not required and not operating. The master advised that preparations were being made for anchoring when water depths permitted. At 0741, the master sounded the ship’s general alarm and instructed the crew to standby inside the accommodation with their lifejackets.

At 0744, Port Kembla VTS called JRCC to report that Portland Bay was drifting towards the coast and ‘could ground in 1.5 hours’. The ship was about 5 miles off the coast in Commonwealth waters and moving rapidly towards New South Wales coastal waters. Immediately afterwards, at 0745, Sydney VTS called JRCC, discussed ‘emergency tug’ activation and advised that Engage Towage was preparing a harbour tug.

On board, at 0746, the master ordered that the boatswain (a senior deck crewmember) go forward along the starboard side (the lee side) and remove the anchors’ lashings. At 0749, another PAN message was broadcast advising that the ship would ground in one hour (the low engine speed allowed little control of the ship’s heading and drift rate). Marine Rescue advised the master that assistance was being arranged and, at 0751, Sydney VTS asked the master to confirm that ‘emergency tug assistance’ was required. Soon after, Svitzer instructed the master of its tug, Bullara, in Port Jackson (Sydney) to prepare to deploy.

At 0752, after Sydney Water Police advised JRCC that 2 water police vessels from Port Botany and Port Kembla were deploying, AMSA took over search and rescue (SAR) coordination for the incident. Soon after, AMSA began identifying air and surface assets to evacuate the crew in case the ship stranded on the rocky coastline. At 0754, AMSA tasked the first asset, a Challenger aeroplane from Essendon Airport, Victoria.

At 0756, Pacific Basin emailed Monson advising that the ship was 1.5 hours away from the shore and asked for an update on tug arrangements. At 0757, Sydney VTS followed up AMSA for the ‘emergency tug’ and was advised that the nominated emergency towage vessel (ETV) for New South Wales (Svitzer Glenrock) was in Newcastle (see the section titled Svitzer Glenrock under Svitzer Australia). Sydney VTS then advised that it would be deploying any available tug(s) in Sydney.

At about 0758, Pacific Basin advised the master that the agent, Monson, was arranging a tug and suggested anchoring when the ship drifted into 45 m depths (expected to be in one hour). At 0800, the master instructed the chief mate to collect important ship certificates and documents and place them in the starboard lifeboat as it was too late for a tug to reach the ship in time.

At about 0800, Engage Towage contacted United Salvage, a salvage services provider, to advise that the disabled ship was drifting towards the shore and it was unlikely a tug could reach the ship before it grounded. As part of an existing agreement between the 2 companies, they decided to mobilise SL Diamantina, an Engage Towage tug in Port Botany with a crew on board. Its most suitable tug, SL Martinique, was not mobilised at that time as it was not crewed (see the section titled Engage Towage).

At 0803, the NSW Maritime manager called JRCC again and was advised that it was ‘trying to organise tugs to assist as soon as possible’.

Meanwhile, Bullara’s crew had boarded at about 0800 and begun preparing to deploy. At 0804, Monson emailed the master (copying AMSA) and advised that a tug was being arranged (Monson had earlier asked Svitzer to provide a tug). A short time later, United Salvage asked Svitzer for Bullara and was advised that it was being prepared for hire by the ship’s owners.

At 0807, Marine Rescue advised the master that a water police vessel was en route and confirmed that the crew had mustered with lifejackets. Between 0800 and 0810, AMSA had contacted the NSW Police, NSW Helicopter Rescue Services, NSW Ambulance Services and the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to request air and surface craft to evacuate the ship’s crew (based on information that a tug could not reach the ship before it drifted on to the shore).

At about this time, the NSW Maritime manager called the Port Authority’s chief operating officer to discuss the information which the manager had obtained from JRCC and the response by New South Wales. They exchanged information, noting that the ship would soon be within New South Wales coastal waters and agreed to convene a meeting of relevant agencies to understand each other’s roles and responsibilities for the response.

Meanwhile, at 0811, the master advised Pacific Basin that a police vessel rather than a tug, was en route to the ship. The master then discussed the anchoring plan with the mates, advising them that when depths reduced to 80 m, 3 shackles[22] of the port anchor cable would be ‘walked back’[23] (veered) and when the depths were 50 m, the anchor would be ‘let go’[24]. The master noted to them that the PAN message suggested by Marine Rescue had not resulted in tug assistance being provided and ordered a distress message (MAYDAY) to be broadcast.

At 0814, the second mate transmitted distress alerts and messages on the ship’s global maritime distress and safety system (GMDSS) equipment. The distress messages were received by AMSA and other stations within one minute. By then, the ship had closed to 3.2 miles off the coastline.

At 0815, Engage Towage advised Sydney VTS that its tug, SL Diamantina, would depart its berth in about 15 minutes (the tug master had advised Engage Towage that its aft towing winch was not operational). Two minutes later, Monson sent an urgent email to the master (copying AMSA) to advise that a tug was being mobilised and Marine Rescue vessels were en route.

At 0822, the master updated Pacific Basin, noting the rocky seabed indicated on the chart in depths of 50 m and advised the intention to anchor in 40 m depths instead. At that time, the ship was 3 miles from the coast and entering New South Wales coastal waters.

In addition to communicating with Monson, Pacific Basin had contacted the ship’s hull and machinery insurance underwriter to seek any immediately available tugs through international salvage companies.

At 0825, Marine Rescue advised the master to expect rescue helicopters in 45 minutes and confirmed that the evacuating crew would assemble on the starboard side of the deck near cargo hold number 5. By 0828, AMSA had tasked 3 rescue helicopters (2 from NSW Ambulance Services and one from Westpac Lifesaver Rescue).

On board, by 0831, the chief mate and crew were on the forecastle and, at 0836, walked back one shackle of both anchor cables. A couple of minutes later, the master advised Pacific Basin that veering further cable with the ship rolling 35° risked fouling (entangling) the 2 chains.

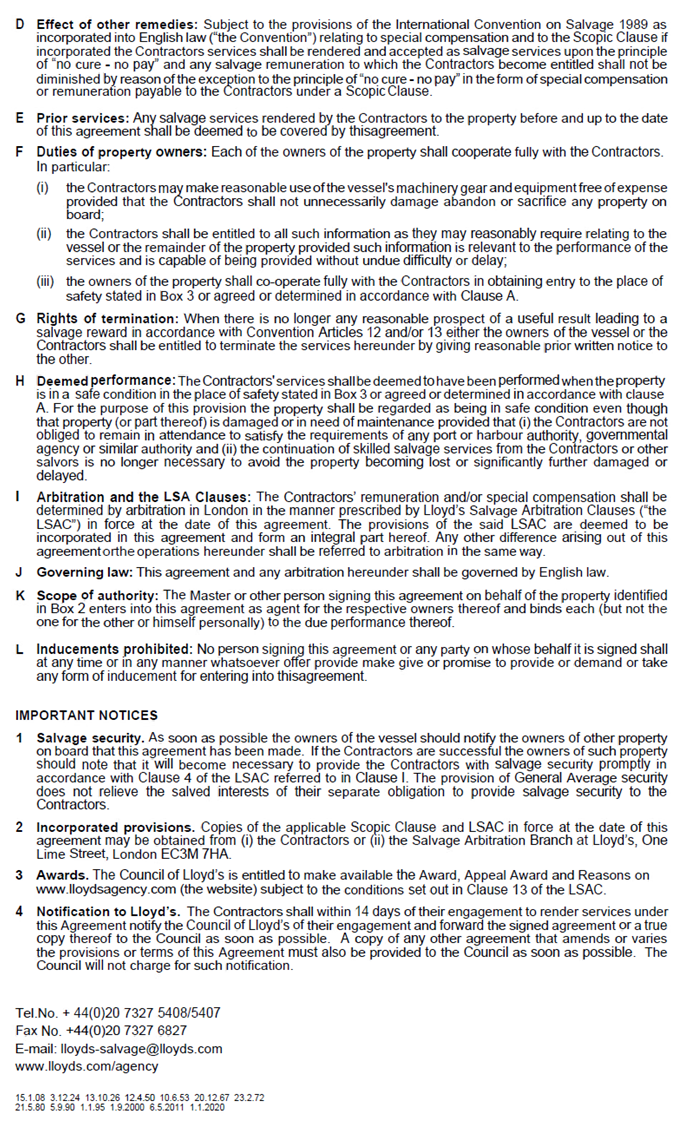

At 0840, AMSA established an incident management team (IMT) for a severity level 3 incident (moderate) as per its internal procedures (see the section titled Maritime Assistance Services procedures under National level). The AMSA Response Centre (ARC)[25] duty manager assumed the incident controller role in this IMT (incident coordinator)[26]. Six minutes later, AMSA formally requested the ADF for assistance indicating that the ‘primary mission is rescue of crew’ because the ship could ground at 0930 on the cliffs south of Wattamolla (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Meanwhile, NSW Police had tasked another helicopter operated by the Rural Fire Service (RFS) to assist with evacuating the ship’s crew.

On board the ship, after further discussion with Pacific Basin, at 0843, the master ordered 2 shackles walked back on both anchor cables. Shortly after, Marine Rescue asked the master to prepare the ship’s towing equipment forward and, if possible, aft.

By 0846, Svitzer had agreed to provide Bullara to Pacific Basin under a ‘TOWHIRE agreement’[27] to assist the disabled ship.

At 0848, SL Diamantina with 3 crew on board departed Port Botany. At 0854, Sydney VTS advised Portland Bay's master that the tug’s ETA was in 90 minutes (about 1025) and to advise when the ship was anchored. Sydney VTS followed up with Svitzer at 0858 and was advised that Bullara was preparing to deploy.

At 0859, SL Diamantina’s master established communications with the ship’s master. Engage Towage advised United Salvage, with which it had partnered to provide assistance, that the tug was en route. The ship was now 1.4 miles from the rocky shore.

Emergency anchoring off Eagle Rock

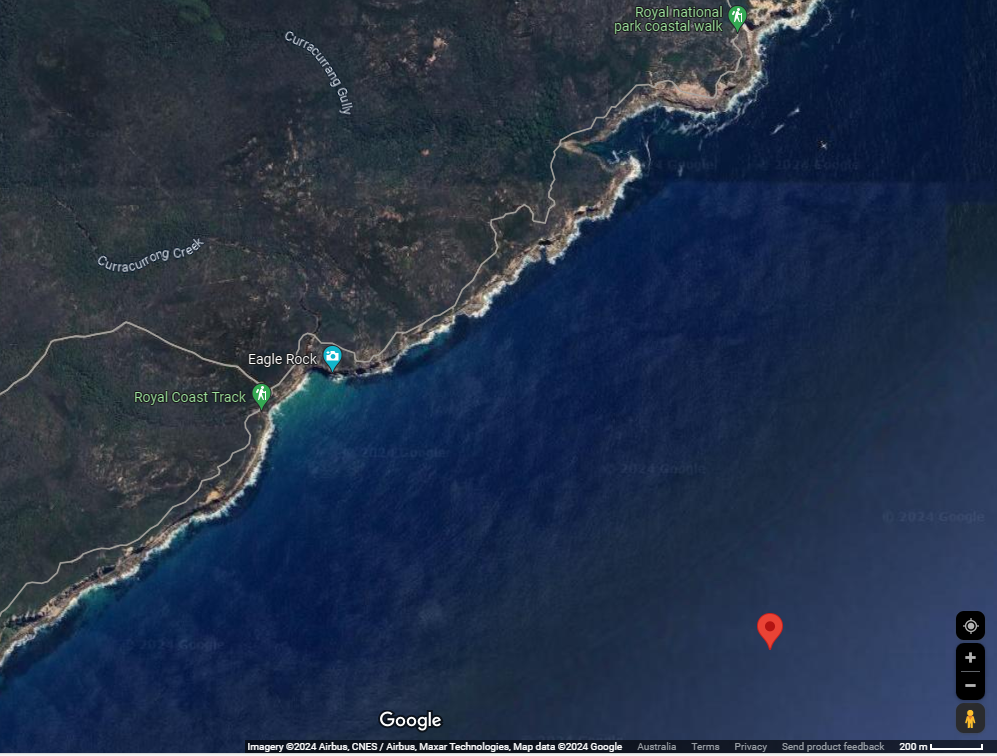

At 0901 on 4 July, the master advised the chief mate to standby to let go the anchors and, at 0905, ordered the port anchor let go. The anchor cable was secured with 9 shackles out with the engine dead slow ahead to relieve load on the cable. The starboard anchor was let go at 0909 and, by 0915, its cable had been secured with 7 shackles out. Soon afterwards, the engine was stopped. The ship was anchored in depths of 45 m with a sandy seabed about one mile from the shore (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Ship’s anchor position (red marker) off Eagle Rock

Source: Google Maps, annotated by the ATSB

While anchoring, the master provided Port Kembla VTS various information requested, including electrical power and engine status, distance to the shore and helicopter winching information. By the time the ship was anchored, one of the 3 rescue helicopters was in its immediate vicinity and had established communications. The other 2 helicopters arrived on scene a short time later.

Meanwhile, at about 0915, United Salvage and Engage Towage began preparing to deploy SL Martinique. The tug was in White Bay, Sydney, but in addition to food, water and stores, it needed to be provided with suitable towing and salvage equipment before deploying.

At 0925, Marine Rescue advised the master to evacuate all but the essential crew required on board for a towing operation. The master discussed the evacuation with Pacific Basin and advised that the tug’s ETA was in one hour and suggested retaining 8 crew for a towing operation.

At 0926, the Westpac Lifesaver Rescue helicopter crew informed AMSA that a fourth helicopter, which was not expected, was in the area. It was soon identified as the RFS helicopter and AMSA instructed its pilot to return to base to avoid conflict with the other 3 rescue helicopters in the area.

At 0930, United Salvage briefed SL Diamantina’s master (via telephone) about the Lloyds Open Form (LOF) salvage agreement to be made with the ship’s master verbally (see the section titled Law of salvage under Salvage). United Salvage advised the tug master that the tug would need to push on the ship’s stern or midships to assist the ship and keep it away from the shore.

At 0937, the ADF advised AMSA that ADV Reliant was en route but the only assistance that this vessel could provide would be to launch its boats.[28]

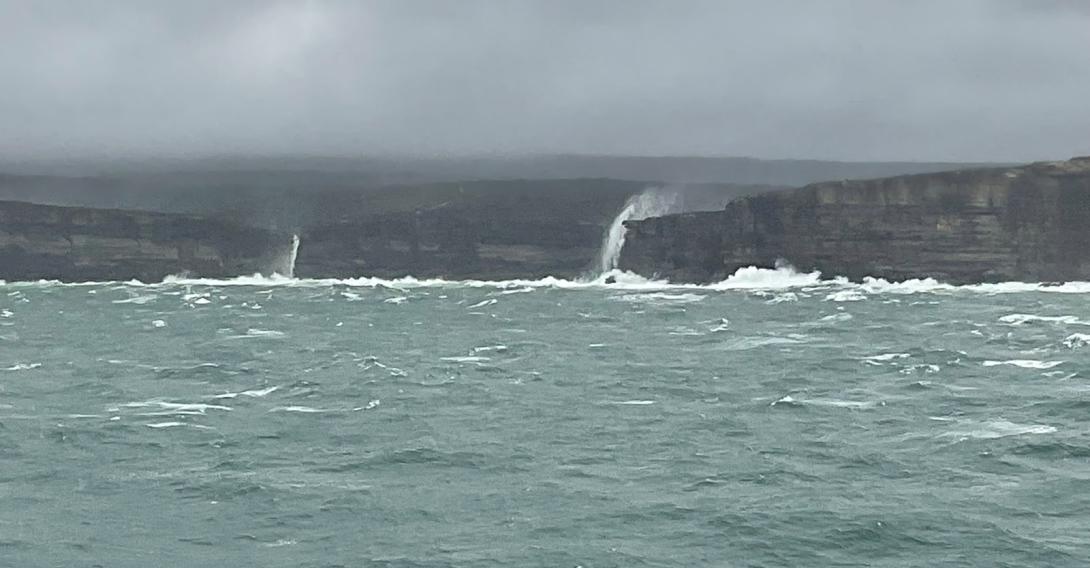

Meanwhile on the ship’s bridge, at 0937, the third mate informed the master that the distance to the shore had reduced to 9 ‘cables’[29] (Figure 6). The master was still discussing the situation with Pacific Basin and suggested evacuating all non‑essential crew, including the 2 trainees on board.

Figure 6: The shore seen from the ship’s bridge

Source: Portland Bay’s master

From about 0945, a meeting involving officers from various responding agencies, including the Port Authority, NSW Maritime and AMSA was held (with most attending virtually). The main aim of this multi‑agency meeting was exchanging information and coordinating their respective roles and responsibilities, including the control agency leading the response.

At 0946, after 3 unsuccessful winching attempts due to the ship rolling and pitching heavily and unpredictably, and the master confirming the anchors were holding, the high‑risk evacuation was abandoned and AMSA instructed the 3 helicopters to return to base. The Challenger aeroplane tasked arrived in the area later but remained at high altitude and assisted with ship‑shore communication.

At about 0950, SL Diamantina’s master read out the LOF salvage agreement to which Portland Bay’s master agreed. At 0958, Svitzer advised AMSA that Bullara was available as Monson had advised that the tug was not required. About 10 minutes later, Monson confirmed to AMSA that it had released Bullara from a commercial perspective (the hire contract).

At 1008, Engage Towage emailed the master, Pacific Basin, AMSA, Monson and others confirming that, together with United Salvage, a LOF salvage agreement was in place and its tug, SL Martinique, was also deploying. Subsequently, when Pacific Basin informed the insurance underwriter that a salvage agreement was in place, the efforts to seek tugs from international salvors was discontinued.

At 1010, SL Diamantina arrived near the ship, which was rolling heavily. Over the next 15 minutes, the tug master assessed the situation, estimating that the south‑east swell was 9 m with waves rising to 12 m in the south‑easterly winds gusting to 45 knots. Rain squalls were reducing the visibility to 150 m.

At about 1020, the multi‑agency meeting concluded with the Port Authority assuming the ‘combat agency’[30] role as per the ‘NSW Coastal Waters Marine Pollution Plan’[31] (see the section titled Legislation and plans under State level). The Port Authority then established an incident management team (IMT) that would meet at 2‑hourly intervals and appointed its chief operating officer as the incident controller (IC). An AMSA liaison officer was assigned to this IMT. The NSW Maritime manager responsible was assigned to be a liaison officer for New South Wales and attended JRCC from just before midday.

Meanwhile, the AMSA IMT established earlier in Canberra was not formally dissolved and its team members continued in their roles to support the combat agency (the Port Authority and its IMT). At 1020, AMSA decided to deploy Bullara in case it was required and advised Svitzer that it would task the tug under their contract (see the section titled Emergency towage services contract under Svitzer Australia).

At 1028, after SL Diamantina’s master and the ship’s master agreed that the tug would push on its starboard side to relieve the load on the anchor cables, the tug began pushing along the midships area. However, after colliding with the shipside several times due to the heavy swell, these efforts were abandoned at 1033 to avoid serious damage.

At 1040, the tug master advised the intention to connect the tug’s towline (a synthetic fibre rope) through the ship’s centre fairlead to its mooring lines. Fifteen minutes later, the towline was connected to 2 synthetic fibre mooring ropes using a towing shackle and the tug master took some weight on the towline.

Meanwhile, both Bullara and SL Martinique had nearly completed their deployment preparations. At 1051, a few minutes after Engage Towage had informed AMSA about the salvage agreement in place, AMSA issued Svitzer a tasking direction for Bullara. Two minutes later, AMSA advised that the tug was to proceed to the scene and standby. Bullara left its berth at 1054. Shortly after, at 1058, SL Martinique with 6 crew on board left its berth under the instructions of United Salvage.

After SL Diamantina’s towline was secured, the ship’s engineers started work to repair auxiliary blower number 2. By 1100, they had removed the blower’s impeller and fitted a blank on the blower trunk (to allow the other blower to be used when operating the engine).

At 1140, AMSA became aware that United Salvage intended to replace SL Diamantina with SL Martinique, and AMSA then calculated the pulling power required to hold the ship and to tow it.

At 1158, the ship’s mooring ropes connected to SL Diamantina’s towline parted. After some difficulty, 2 mooring wires were connected to the towline at 1220. However, 10 minutes later, the wires also parted and efforts began to reconnect the towline.

At 1230, AMSA contacted United Salvage and was advised that it intended ‘to only use SL Martinique to tow’ and that there was ‘no requirement for Bullara’.

Meanwhile, the second meeting of the Port Authority’s IMT was held from about 1230. At this meeting, the IC asked the AMSA liaison officer for Svitzer Glenrock to be activated in case it was required for the response.

By 1244, SL Diamantina’s towline had been reconnected. About 20 minutes later, however, it parted again. A few minutes later, the ship’s master asked that no further attempts be made to connect the towline.

At 1324, AMSA released the Challenger aircraft that had remained above the ship’s location and it returned to base.

By 1400, the engineers had fitted a new impeller in the blower. Their attempts to fit a new electric motor had not been successful due to difficulties removing the existing motor’s pulley and the repairs were suspended.

At 1402, SL Martinique arrived near the ship and, shortly after, began connecting its aft towing wire to the ship’s port bow. A few minutes later, Bullara arrived at the scene and, at 1410, AMSA advised Svitzer that it had the option to make Bullara available to United Salvage under the LOF agreement or the AMSA contract (see the section titled Emergency towage services contract under Svitzer Australia). At 1413, AMSA also advised United Salvage that Bullara was available to assist the ship.

The ship’s anchors had continued dragging slowly and it was now about 7 cables from the shore. At 1425, United Salvage requested AMSA for the use of Bullara, which it approved with the same advice about contractual terms provided earlier to Svitzer.

At 1430, Pacific Basin advised AMSA that the ship’s engine could be operated at limited rpm (up to half ahead). By 1433, SL Martinique’s towline had been secured. Shortly after, Bullara began connecting its main aft towline (wire) to the ship’s starboard bow and, by 1455, it was secured. By this time, the IC had decided that the ship would be towed 20 miles from the coast under United Salvage’s direction (ports in and near Sydney were closed due to the bad weather).

Attempted tow to sea

At 1505 on 4 July, Portland Bay’s master began weighing the anchors. The main engine was used to assist and, by 1538, both anchors were home. At 1540, SL Martinique and Bullara started the tow with SL Diamantina following the ship (Figure 4). The engine was at slow ahead to assist, however, it was stopped at 1547 due to high temperatures caused by ‘scavenge space fires’[32].

With the ship under tow, AMSA released ADV Reliant from tasking at 1553. About 20 minutes later, AMSA also released the 2 water police vessels at the scene from SAR tasking.

At 1828, United Salvage asked the IC to open Port Botany for the ship to take shelter there (refuge) as, in the prevailing weather, the tow had progressed parallel to the coast (towards Sydney) rather than away from the coast. Minutes later, at 1835, Bullara’s towline parted at its inboard (tug) end and the wire fell into the water (its other end remained connected to the ship’s bow). SL Martinique was not able to tow the ship on its own but remained connected with little or no weight on the towline. The tug’s master had earlier injured their left shoulder but was able to continue working.

At 1839, United Salvage advised Svitzer and Engage Towage that Bullara’s towline had parted (it had no spare towing wire) and the ship’s engine could not be used. United Salvage then called AMSA and asked it to activate the ETV, Svitzer Glenrock, or to have Port Botany opened (see the section titled Incident management). At 1850, while considering the ETV request, AMSA convened a meeting with Svitzer and United Salvage to discuss whether ocean‑going towing equipment was available in the general area for use by harbour tugs.

Meanwhile, Portland Bay with SL Martinique’s towline connected, was drifting towards Bate Bay (Figure 4). The master decided to anchor again when water depths reduced sufficiently and prepared to deploy both anchors.

At 1901, United Salvage advised Svitzer that a request for refuge in Port Botany had been made and asked if the ETV could be ‘mobilised’. Svitzer advised that if AMSA did not activate it, the tug could be hired under a TOWHIRE agreement (see the section titled Incident management).

Shortly after, the IC called AMSA’s Maritime Emergency Response Commander – MERCOM (see the section titled Response commander under Pollution prevention) to follow up the request for the ETV made that afternoon via the AMSA liaison officer. The MERCOM was unaware of the request but agreed to activate the ETV. The MERCOM also offered to issue a ‘direction’[33] to facilitate the ship to be towed into Port Botany (see the section titled Place of refuge under Pollution prevention). The IC advised that the port was closed due to the weather so the ship could not be towed into port until the weather improved.

At 1945, United Salvage submitted a formal ‘place of refuge’ request via email to the MERCOM to allow the ship to be moved to Port Botany.

At 1957, AMSA issued a tasking direction for Svitzer Glenrock. Svitzer immediately instructed the ETV’s Newcastle‑based crew to prepare to deploy for the nearly 90‑mile passage to the ship’s location off Bate Bay.

At 2010, United Salvage stood down SL Diamantina as it was low on fuel and it returned to Port Botany. Other than its towing lines, the tug had no reported damage. The tug’s chief engineer had injured a knee and shoulder during the deployment but had been able to continue working.

The Port Authority’s IMT considered options to evacuate the ship’s crew if it became necessary due to the risk of stranding and Sydney VTS checked if any other tugs or vessels were available. No tugs were available in Sydney and a naval vessel there would take at least 4 hours to mobilise. By 2015, it was concluded that helicopter rescue operations would not be possible in darkness.

At 2030, Svitzer Glenrock’s crew boarded and began pre‑departure and towing gear checks.

Emergency anchoring off Bate Bay

At 2035 on 4 July, Portland Bay’s port anchor was let go in 40 m water depths where the seabed was sandy and 9 shackles were paid out. Five minutes later, the starboard anchor was let go and 6 shackles were paid out. By 2045, both anchors had been secured with the ship 1.4 miles from the coast. The south‑easterly swell off Sydney recorded at the time was 5.03 m (average) and 8.63 m (maximum).

The IMT continued monitoring the situation through Sydney VTS with a Sydney harbour pilot attending the VTS. SL Martinique maintained a static tow and increased weight on its towline when required to prevent the ship dragging its anchors. Bullara remained near the ship. The 2 tugs were the only surface assets available for a rescue operation if it became necessary.

In Newcastle, Svitzer Glenrock left its berth at 2227. At sea, the ETV’s master reported that in the 40‑knot south‑south‑east winds with 8 m waves and poor visibility, it could only make good a speed of about 5 knots. Meanwhile, AMSA’s search for ocean‑going towing gear had identified that Coral Knight, the level 1 ETV in Queensland, had such equipment.

At 0121 on 5 July, the rate at which the ship was dragging its anchors increased and the pilot asked for the weight on SL Martinique’s towline to be increased slightly to reduce the dragging.

Meanwhile, Svitzer Glenrock continued its passage with an ETA off Bate Bay of about noon.

During the night, AMSA continued monitoring the ETV’s ETA and the position of the ship, which was dragging its anchors at a rate of about 100 m per hour. At 0546, the MERCOM acknowledged United Salvage’s place of refuge request and advised that the ETV was due on scene at about midday with plans underway to move the ship to Port Botany, noting that it had not yet grounded. At 0717, following a request by AMSA Operations for the ‘need to evaluate the port of refuge’, the subject was discussed by its incident management team.

At 0848, the incident was upgraded to level 5 (severe) in accordance with AMSA’s procedures (see the section titled Maritime Assistance Services procedures under National level) noting ‘machinery failure and immediate tasking of ETV’. The ARC duty manager continued coordinating AMSA’s response to the incident with the MERCOM continuing to oversight response activities.

At 0900, the Port Authority IC asked the MERCOM to issue directions to facilitate the ship to be towed into Port Botany in daylight the following day (see the section titled Incident management). At 1145, the IC convened a meeting with United Salvage, Engage Towage and Sydney Pilots to plan the towage operation.

At 1257, AMSA held a meeting where the MERCOM advised the IC that Svitzer Glenrock would remain in AMSA control for the towage operation. Collectively, they decided that the Port Authority would continue managing the incident as the combat (control) agency until the ship was safely berthed. They agreed that AMSA would then exercise its regulatory functions as the safety authority.

At 1300, when Svitzer Glenrock arrived off Bate Bay, United Salvage asked for Bullara’s parted towline to be recovered. The wind had moderated to 30 knots, but the 8 m swell that remained made recovering the 200 m towing wire difficult.

By 1415 Bullara had recovered its towline and Svitzer Glenrock began connecting its towline. By 1515, the towline had been secured through the ship’s forward centre lead. Shortly after, Bullara was dismissed to return to port (other than its parted towline and minor damage on deck, the tug was not damaged). Svitzer Glenrock and SL Martinique remained with the ship and maintained a static tow.

At about 1605, AMSA emailed MERCOM’s directions to Portland Bay’s master, Pacific Basin, United Savage and the Port Authority, requiring the ship to be towed to a suitable berth in Port Botany (see the section titled Incident management).

Later that afternoon, United Salvage presented the towage plan prepared using the ship’s emergency towing procedure (see the section titled Incident management). The plan involved the use of Svitzer Glenrock and 3 Engage Towage tugs (SL Martinique, SL Fitzroy and SL Diamantina). At about 1800, after discussing the plan with the MERCOM, the IC approved it subject to suitable weather conditions (maximum swell 4 m) and daylight hours. They agreed that the operation could start at about 0800 on the following day, 6 July.

Refuge in Port Botany

At 0722 on 6 July, SL Fitzroy arrived off Portland Bay in preparation for the tow. At 0845, a pilot vessel arrived with a United Salvage representative, a service engineer (representing the ship’s main engine manufacturer) and 2 Sydney harbour pilots on board.

By 0936, SL Fitzroy’s towline had been secured through the ship’s aft centre lead. The pilots, salvor’s representative and service engineer had boarded the ship by 0954 and, at 1000, the master began weighing the anchors.

At 1051, both anchors were home and secured and, soon after, the ship was under tow with 3 tugs connected (Svitzer Glenrock, SL Martinique and SL Fitzroy). The main engine was used at dead slow ahead to assist the tow.

At 1228, the ship entered the port limits of Port Botany. SL Diamantina had arrived to assist with berthing and, at 1312, connected a towline to the ship aft.

At about 1409, the ship was alongside Hayes Dock berth 3. By 1454, all its mooring lines had been secured and all 4 tugs had been cast off and dismissed.

Shortly after, AMSA officers attended Portland Bay and carried out initial inquiries and inspections. At 1650, AMSA issued the master with a notice to detain the ship.[34] The reason for the detention was identified as ‘main propulsion system not able to reliably provide intended propulsion service’, which effectively made the ship unseaworthy. No damage was reported to have occurred due to the ship’s anchoring and towing operations and no‑one on board was injured during the incident.

By this time, various investigations into the incident, including those initiated by the ATSB, AMSA and Pacific Basin, had commenced with their investigators collecting relevant evidence on board the ship.

Inspections and repairs

On 7 July, an AMSA Port State Control inspection identified 14 deficiencies with Portland Bay’s main engine and associated machinery, including:

- auxiliary blower number 2 not operational

- non‑return flap in scavenge manifold stuck open

- piston rings of all main engine units stuck due to excessive carbon deposits.

Pacific Basin submitted a plan to rectify all the deficiencies over the following week while berthed in Port Botany by carrying out the following work under the supervision of the main engine manufacturer:

- overhaul of all main engine units

- overhaul of auxiliary blower number 2

- inspection and cleaning of main engine charge cooler

- checking of the condition of main engine turbocharger

- ordering spares (blower, non‑return valve and piston rings)

- post‑repair main engine tests and ship’s classification society surveys.

The planned repairs were carried out over the following days in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations (see the section titled Post‑incident inspections under Propulsion).

On 13 July, the main engine was tested to the satisfaction of the ship’s classification society surveyor and engine manufacturer’s representative with an AMSA surveyor in attendance. The ship was then released from detention and, at about 1700, departed Port Botany for Gisborne, New Zealand.

Context

Portland Bay

General details

Portland Bay was a geared ‘handysize’[35] bulk carrier designed to carry dry bulk cargoes and timber (Cover). At the time of the incident, the ship was owned by Uhland Shipping, British Virgin Islands, and operated and managed by Pacific Basin Shipping, Hong Kong[36] (Pacific Basin). The ship was registered in Hong Kong and classed with Nippon Kaiji Kyokai, Japan (Class NK).

The ship was built in 2004 by Imabari Ship Building Company, Japan. It had a gross tonnage[37] of 16,960, an overall length of 169.26 m, a breadth of 37.20 m and depth of 13.60 m. At a summer draught of 9.78 m, the ship had a deadweight carrying capacity of 28,446 tonnes.

Four cargo cranes serviced the ship’s 5 cargo holds and fixed posts to lash timber cargoes were fitted on both sides of its main deck. The ship’s flush main deck extended to the forecastle where the mooring equipment, including electro‑hydraulic windlasses for the port and starboard anchors were located. Each anchor was fitted with 10 shackles[38] of 70 mm diameter chain cable.

Portland Bay’s navigation bridge (bridge) was equipped with navigational equipment in accordance with SOLAS[39] requirements for a ship of its size. This included 2 radars, 2 electronic chart display and information system (ECDIS) units, 2 very high frequency (VHF) radios and an automatic identification system (AIS) transceiver. A Qingdao Headway Marine model HMT‑100A voyage data recorder (VDR) recorded data for the time of the incident, including bridge audio.

Crew

At the time of the incident, the ship had a crew of 21, including the master. Thirteen of them, including the master and chief engineer, joined the ship in Port Kembla on 21 or 22 June 2022. All the crew, except for the Ukrainian master, were Filipinos.

The officers comprised the master, 3 deck officers (chief, second and third mate) and 3 engineers (chief, second and third engineer), all appropriately qualified for their positions. Others included 5 deck crew, 3 engine crew (a fitter and 2 motormen), one deck cadet and one engine cadet.

The master’s seagoing career began in 1999 with command first gained in 2004. The master had joined Pacific Basin in 2017 and completed 4 assignments as chief mate before being promoted in 2020. In 23 years at sea, the master had mostly worked on bulk carriers and some container ships as well as heavy‑lift cargo ships. The master had not previously sailed on Portland Bay but had on similar ships. The master’s handover notes, checklist and familiarisation, completed on 21 and 22 June, indicated that the ship, its machinery and equipment were in good working condition. That assessment had been confirmed by the outgoing master and chief engineer.

The chief engineer went to sea as a rating in 1992, progressed through the ranks in 3 different companies and, in 2015, obtained chief engineer qualifications. In 2016, he joined Pacific Basin and worked on its ships as a second engineer until being promoted to chief engineer in 2021. He joined Portland Bay for the first time on his second assignment as chief engineer. The chief engineer’s handover checklist indicated that the only major work planned for the following month was the renewal of the exhaust valves on 2 main engine units, with no issues of ongoing concern.

Propulsion

Portland Bay’s propulsion was provided by a Makita Mitsui MAN B&W 6S42MC diesel engine that could deliver 5,850 kW at 129 rpm. The main engine drove a single, fixed‑pitch, four‑bladed, right‑handed propeller. The ship’s designed service speed at 122 rpm (that is, 85% of the engine’s maximum continuous rating) was 14 knots (laden) and 14.5 knots (in ballast).

The ship’s propulsion (single engine and propeller), power and design speed were typical for its size and type with no auxiliary propulsion or thrusters. Table 1 below shows relevant data from the ship’s manoeuvring (harbour speed) table. The indicative speeds in the table were based on full propeller immersion, which occurred when the aft draught was 5.1 m or more.

Table 1: Portland Bay’s manoeuvring speed information

| Engine order | Speed (rpm) | Laden speed (knots) | Ballast speed (knots) |

| Dead slow ahead |

42 |

5.1 |

5.3 |

| Slow ahead |

58 |

7.1 |

7.3 |

| Half ahead |

80 |

9.6 |

9.9 |

| Full ahead |

90 |

10.6 |

11.1 |

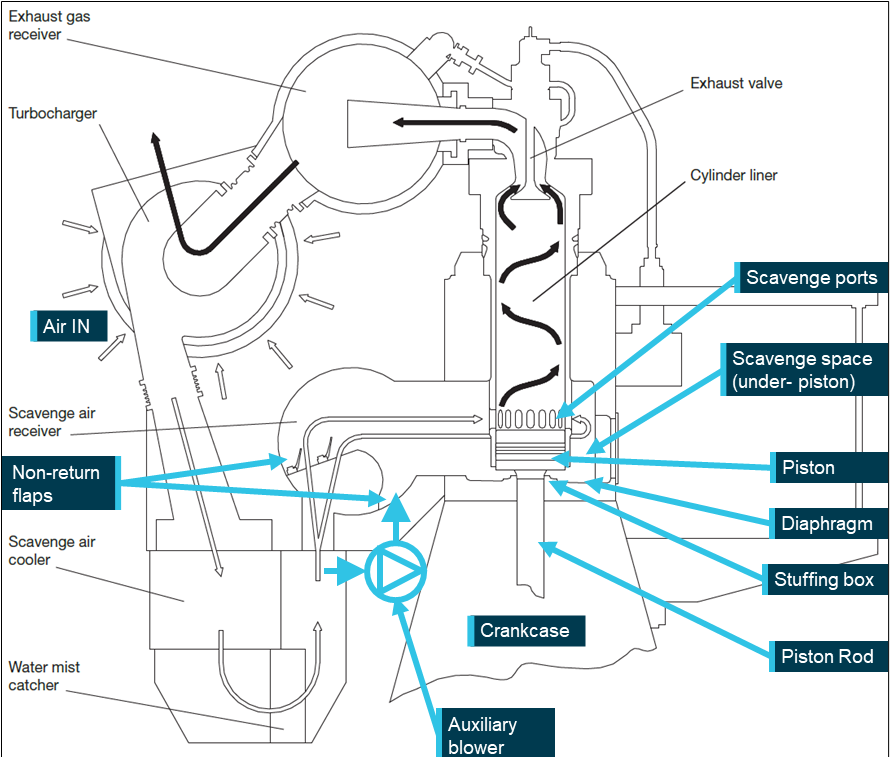

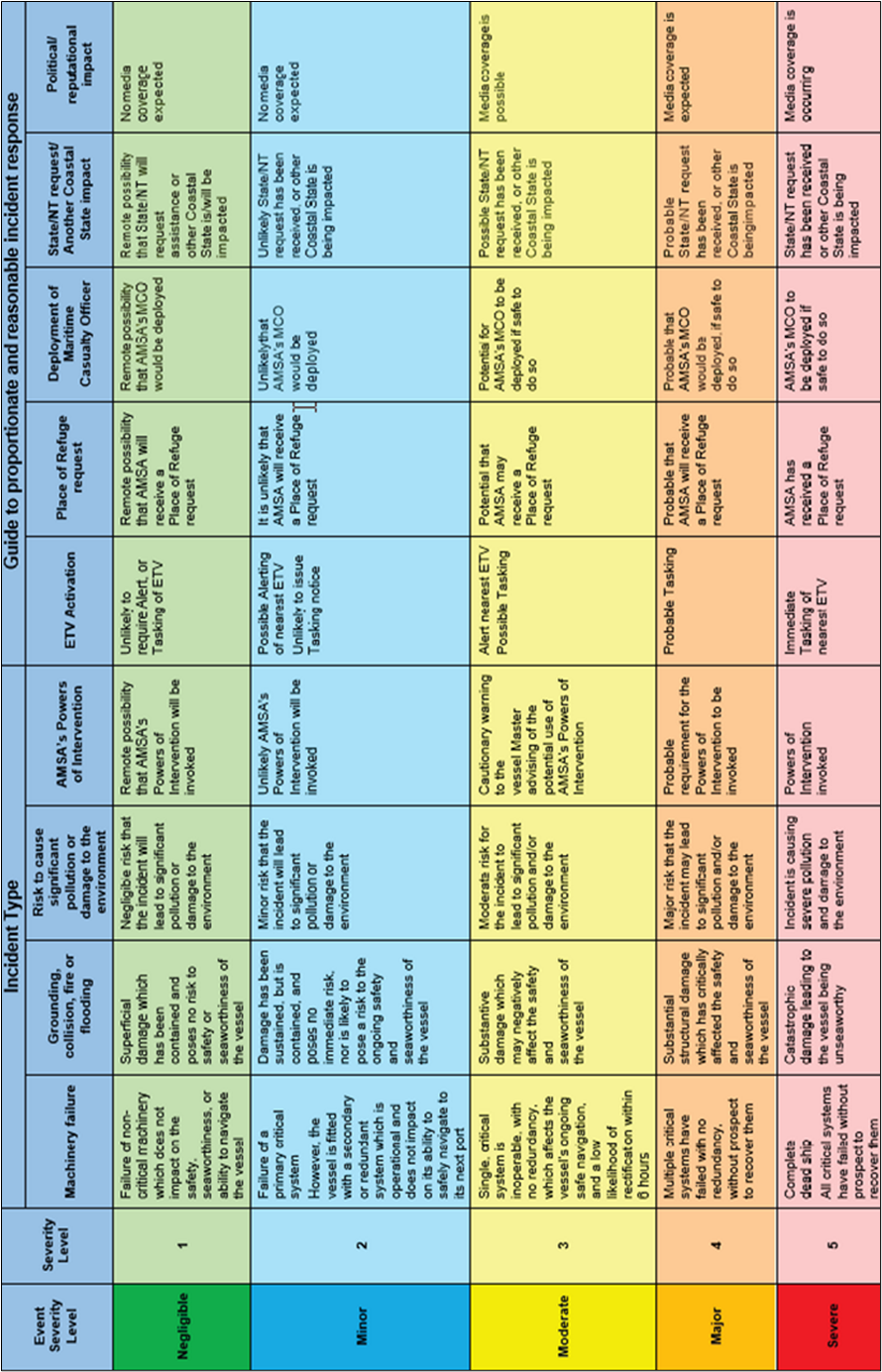

Air for fuel combustion (scavenge air) was drawn from the engine room through filters into the turbocharger compressor (Figure 7). The turbocharger compressed the air and discharged it to the scavenge air cooler, which cooled and dried the air before passing the outlet via non‑return flaps.

Figure 7: Slow speed MAN B&W diesel engine combustion air and exhaust system

Source: MAN B&W, annotated by the ATSB

Pressurised air from the cooler went into the scavenge air receiver or trunk, which extended the entire length of the engine and was connected to each cylinder through a pipe in the under‑piston scavenge space. As the piston came down, scavenge ports (cutouts) in the lower cylinder liner were exposed, allowing air into the cylinder above the piston. In combination with the now open exhaust valve at the top of the cylinder, the scavenge air cleared the cylinder of combustion gases and provided fresh air for the next combustion cycle. As the cycle continued, the piston moved up, blocking the scavenge ports, the exhaust valve closed, the air was compressed (increasing its temperature), atomised fuel was injected in and when the piston reached top dead centre, combustion occurred. Expanding gases then forced the piston down for the repeat cycle.

Combustion gases were cleared from the cylinder as the exhaust valve opened and the scavenge ports were uncovered. The combustion gases then passed into the exhaust gas receiver and to the turbocharger turbine side to drive the compressor and draw fresh air into the engine. The exhaust gases from the turbocharger discharged to atmosphere through the exhaust trunk (inside the engine room funnel).

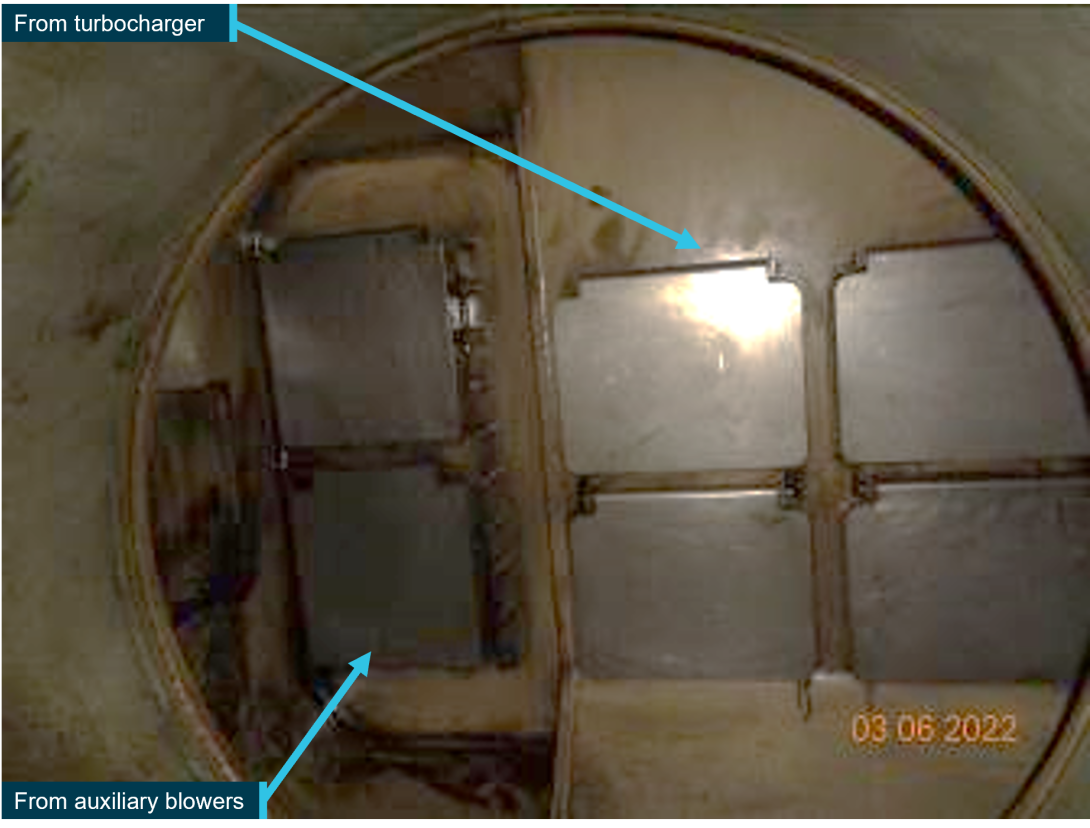

At low engine loads (below 30–40% of maximum load), air supply was boosted by 2 electrically‑driven auxiliary fans or blowers. The auxiliary blowers provided air to the engine until there was sufficient exhaust gas to drive the turbocharger and supply the required volume and pressure of air. The blowers generally operated in automatic mode providing air at low engine load (speed) and stopped operating at higher load (speed) when the exhaust gas‑driven turbocharger could meet the demand for air. The blowers drew air from the charge air cooler outlet and discharged it through non‑return flaps, directly into the scavenge trunk (Figure 8). In effect, the blowers pumped air around the turbocharger non‑return flaps.

Figure 8: Air system non‑return flaps

Source: Pacific Basin, annotated by the ATSB

Complete combustion was essential for the efficient operation of the main engine. The combustion, in turn, relied entirely upon a consistent, reliable air supply. It was therefore critical for the scavenge air system to be sufficiently airtight, particularly at low engine load/speed. The following 3 running surfaces in the air system sealed the system from leakage:

- Auxiliary blower shaft seal.

- Piston rings sealing the cylinder combustion space from the under‑piston scavenge space (loss of this seal could result in piston ring blow by leading to sludge accumulation in the scavenge space, loss of cylinder pressure, poor combustion and scavenge fires).

- The seal between the scavenge space and the crankcase (through the diaphragm, sealing around the piston rod), known as the stuffing box.

In addition to scavenge air loss due to leakage, the following could lead to inefficient combustion:

- Loss of auxiliary blower effectiveness due to air flow recirculation, such as leaking turbocharger non‑return flap(s) allowing air to flow about the blower, from discharge to suction (disrupts blower throughput and reduces scavenge trunk pressure and air flow for combustion).

- Air flow restrictions from:

- fouled scavenge ports due to accumulated deposits from piston ring blow by, stuffing box leakage or dirty air,

- turbocharge fouling (turbine or compressor),

- dirty turbocharger inlet filters,

- air cooler fouling.

- Scavenge fire (ignition of combustible material accumulated in the scavenge space above the diaphragm).

A scavenge fire consumes air for combustion and can seriously damage components if not extinguished quickly. Poor atomising of fuel, excessive fuel supply (for the available air), piston ring blow by, stuffing box leakage and excessive cylinder lubrication can all produce combustible material.

Ship’s engine performance

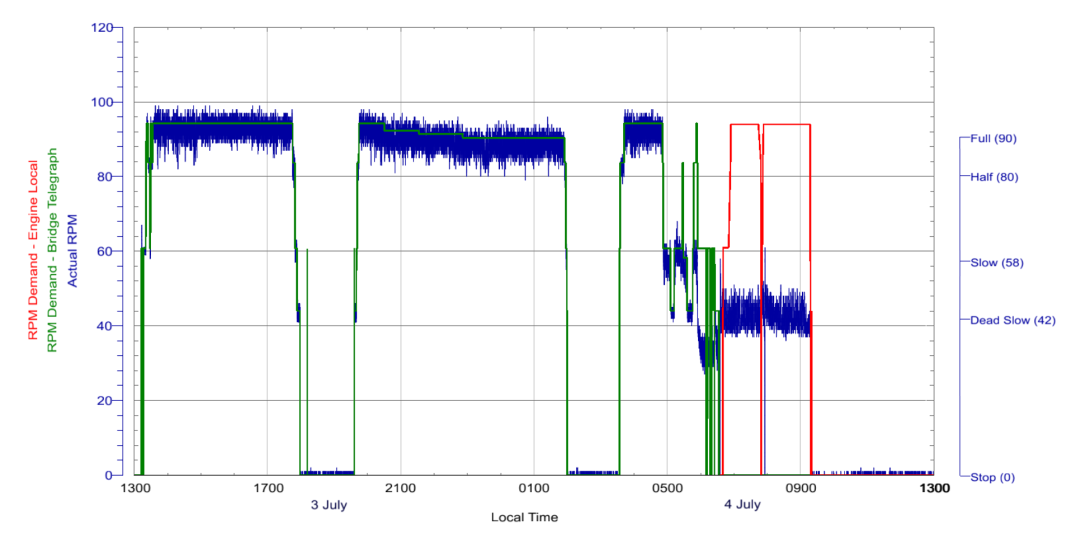

After Portland Bay left Port Kembla on 3 July and the pilot disembarked, the main engine order (demand) was set at full ahead (90 rpm). The engine rpm achieved fluctuated widely about the demand (90 rpm) as the ship (in ballast condition) rolled and pitched heavily in the prevailing weather conditions with its propeller not always fully immersed (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Engine speed demand (green or red) and actual speed (blue) on 3 and 4 July

Source: Portland Bay’s recorded voyage data, annotated by the ATSB

Subsequently, the ship drifted and intermittently steamed slowly with both the auxiliary blowers operating. At 0450 on 4 July, when a fire alarm activated, the engineers observed smoke and a burning smell from blower number 2 and manually stopped it (the motor did not trip). Inspections later identified that the blower’s impeller bearings had failed.

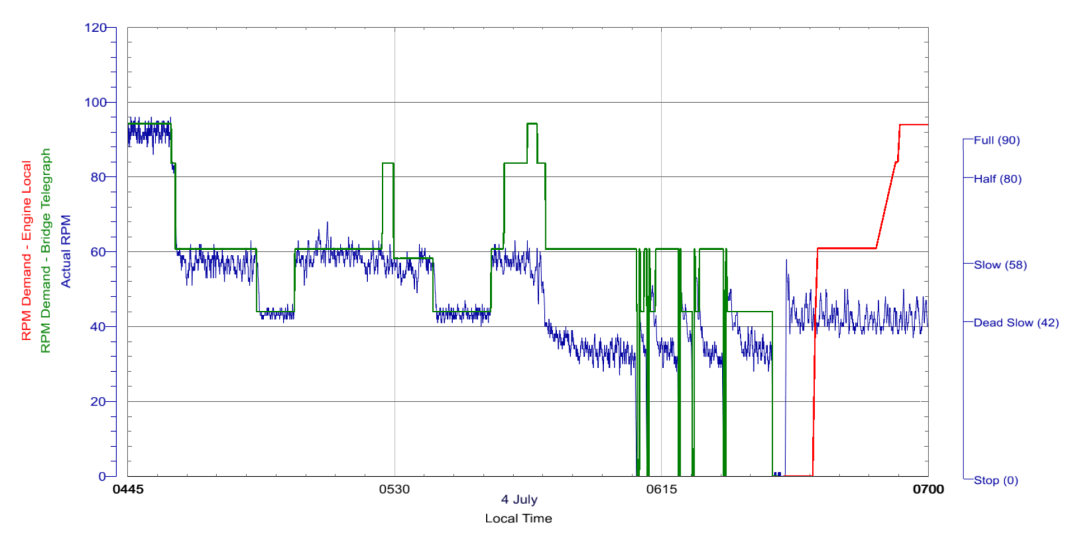

After the failure of auxiliary blower number 2, the engine speed continued to follow the demand for dead slow and slow ahead. However, after about 0550, when attempts were made to increase speed beyond slow ahead, the engine did not respond to the speed demand (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Speed demand (green or red) and actual speed (blue) from 0445 to 0700, 4 July

Source: Portland Bay’s recorded voyage data, annotated by the ATSB

The varying engine load and speed led to adverse engine operating conditions, including:

- poor combustion

- turbocharger surge

- scavenge trunk pressure fluctuations

- fluctuating, and frequent, excessive and mismatched, fuel and air flow

- repetitive opening and closing of scavenge system non‑return flaps

- sticky piston rings, blow by and scavenge fires.

These operating conditions eventually resulted in the main engine being unable to achieve more than about 40 rpm. Overriding normal engine operating control limits and attempting to operate the engine locally (emergency control) to manually control the fuel supplied did not improve engine performance.

Main engine maintenance

When inspected after Portland Bay berthed in Port Botany on 6 July, the main engine had recorded 90,388 running hours. The ship’s planned maintenance system (PMS) was consistent with and supported the Class NK continuous machinery survey (CMS) requirements for classed machinery, including the main engine. There were no outstanding engine maintenance requirements and all the engine units had less than 5,000 running hours since their last inspection.

On 3 June (one month before the incident), the scavenge spaces were inspected and cleaned as part of routine maintenance. The inspection report showed the scavenge spaces and ports and the piston crowns and rings were clean and in generally good condition.[40] The report indicated that the auxiliary blowers and non‑return flaps were clean and intact.

Later in June, while en route to Port Kembla, there were difficulties maintaining full sea speed (122 rpm) due to high scavenge air and engine lubricating oil (LO) temperatures. It was therefore decided to clean the LO cooler, LO filter and charge air cooler when berthed in Port Kembla. In addition to these prioritised tasks, other tasks planned for the port stay included replacing the impeller and bearings in auxiliary blower number 2 with new spares.

About 3 years before the incident, in April 2019, auxiliary blower number 2 had failed and been repaired. The blower failed again in November 2019 and was repaired and, in June 2021, its motor and impeller bearings were replaced.

In March 2022, vibration monitoring revealed abnormal vibrations from the blower. The inspection identified a cracked impeller, damaged shaft bearings and worn bearing housings. The impeller was replaced with a previously used impeller. The cracked impeller was weld repaired and about a month later, in April 2022, it was refitted in the blower without rebalancing. New bearings were fitted in the same worn bearing housings as there were no spares on board.

In late May 2022, a new impeller and bearing housings were received when the ship was in China. As the ship’s operations there, and subsequently in Susaki, Japan, did not allow the new spares to be fitted, this task was postponed until the ship was in Port Kembla as noted above. The priority tasks (LO cooler, LO filter and charge air cooler) were completed from 22 to 26 June but the maintenance for auxiliary blower number 2 was outstanding when the ship left port on 3 July.

The impeller’s unbalanced operation was exacerbated by the varying engine load conditions after the ship left Port Kembla, resulting in the blower’s failure on 4 July. Later that day, the engineers removed the impeller and fitted the new impeller and bearings. They assumed that the electric motor was damaged (burnt out), tried removing it but found its belt drive pulley difficult to remove. The repairs were then abandoned without testing the motor with the blower deemed inoperable and remaining out of service for the duration of the incident.

Following the incident, when the ship was in Port Botany, the electric motor was removed and sent ashore for overhaul. Apart from some in‑service wear and tear, the motor was found to be operational.

After the incident, the main engine manufacturer’s service department, MAN PrimeServ, conducted an engine inspection and service while the ship was in Port Botany to identify reasons for the engine speed not increasing beyond 40 rpm, and carrying out necessary repairs. The inspection and service included:

- overhaul of all pistons and calibration of cylinder liners

- inspection of scavenge spaces including scavenge air receiver, non‑return flaps and under piston scavenge spaces and stuffing boxes

- charge air cooler removal and clean

- overhaul of auxiliary blower number 2.

The inspection identified several issues with engine components, including:

- piston, ring and ring gap measurements close to wear limits

- sticky piston rings on all pistons

- cylinder liner measurements all well within limits

- carbon build‑up in cylinder liner scavenge ports

- a leaky fuel injector

- a damaged turbocharger non‑return flap

- a non‑return flap for auxiliary blower number 2 stuck open

- excessive carbon build‑up and unburnt fuel in the turbocharger

- excessive cylinder lubrication and piston blow‑by in some cylinders

- dirty scavenge spaces with excessive sludge and carbon build up in the air receiver and around stuffing boxes.

A build‑up of carbon, fuel and deposits throughout the scavenge system, pistons, turbocharger and other engine components was also evident. Figure 11 shows the condition of a piston (a), stuffing box (b), scavenge ports (c) and turbocharger turbine housing (d).

Figure 11: Condition of some engine components

Source: Pacific Basin and MAN PrimeServ, annotated by the ATSB

The build‑up of carbon, fuel and deposits was assessed as probably being the result of:

- speed fluctuations resulting in excessive fuel injected into the engine leading to incomplete and unstable combustion

- piston blow‑by due to sticky piston rings caused by poor combustion, excessive fuel injection, excessive cylinder lubrication and a leaky fuel injector

- excessive cylinder lubrication leading to excess oil in the under‑piston space.

The inspection and service concluded that the principal reason that the engine was unable to increase speed beyond about 40 rpm was insufficient air for combustion.

The condition of each engine component, on its own, was within specifications and was not considered enough to disrupt the combustion air flow to the extent of preventing the engine achieving the speed demanded. However, wear and fouling of multiple engine components, together with the loss of the auxiliary blower and open scavenge system non‑return flaps were considered, in combination, enough to prevent the engine from receiving enough air to increase speed past about 40 rpm, regardless of demand.

Class NK required a performance test to be conducted with a report provided to the engine manufacturer. The engine service described above was followed by an engine trial on 13 July while berthed in Port Botany with the manufacturer’s representative, Class NK surveyor and AMSA surveyor in attendance. A sea performance trial was conducted later to the engine manufacturer’s satisfaction.

Planned maintenance system

The ship’s planned maintenance system (PMS) noted above incorporated Class NK machinery survey requirements and was part of the shipboard safety management system (SMS). The engine manufacturer’s instruction manuals were available for carrying out maintenance and repairs in accordance with the PMS. The procedures and guidance available on board covered necessary engineering matters, including avoiding, detecting and extinguishing scavenge fires.

In addition, Pacific Basin’s dedicated manager for the ship oversighted and supported shipboard engineering matters. As auxiliary blower number 2 had been working satisfactorily, fitting the new spares were not prioritised over other tasks by the ship’s manager and the chief engineer.

Safety management system

Portland Bay’s safety management system (SMS) was intended to cover all shipboard operations with some procedures for navigation (bridge) and emergencies directly relevant to this incident.

Navigation‑related procedures were contained in the Bridge Manual of the SMS.[41] The procedures referenced recognised industry standards and guidance, including SOLAS, International Maritime Organization (IMO) guidelines and the Nautical Institute’s Bridge Team Management guide.

The procedures required that, in adverse weather, masters increase distance from navigational dangers to 20~50 miles, as reasonably practicable, to maintain a safety margin. The margin was required to be sufficient to ensure that adequate time would be ‘available to respond to contingencies at sea such as machinery failures (main engine, steering and generators)’.

According to Pacific Basin, it did not encourage drifting to reduce fuel consumption and procedures advised masters to not hesitate adjusting course and/or speed, including ‘heaving‑to’[42], in heavy weather to avoid damage to the ship and its machinery. If the master decided to drift, the ship was required to be about 50 miles from the nearest land or navigational danger, where practicable.

The bridge heavy weather checklist stated that anchors were designed to hold the ship in sheltered waters. It warned against anchoring in adverse weather (wind force 6 or swell higher than 1.5 m). If anchoring in depths less than 40 m, the anchor had to be walked back (veered) within 5 m of the seabed before it was let go. In depths of 40 m or more (defined as deep water), the anchor had to be walked back throughout, with the ship stationary over ground. Anchoring in depths greater than 100 m was prohibited except in an emergency and it was noted that the windlass was only designed to lift the anchor and 3 shackles (about 85 m) of cable.