What happened

At about 0947 local time on 2 June 2025, a Piper PA-28 was returning to Bankstown Airport, New South Wales, from the west via the 2RN radio towers, the inbound reporting point to Bankstown Airport, at the conclusion of a training flight with an instructor and student on board.

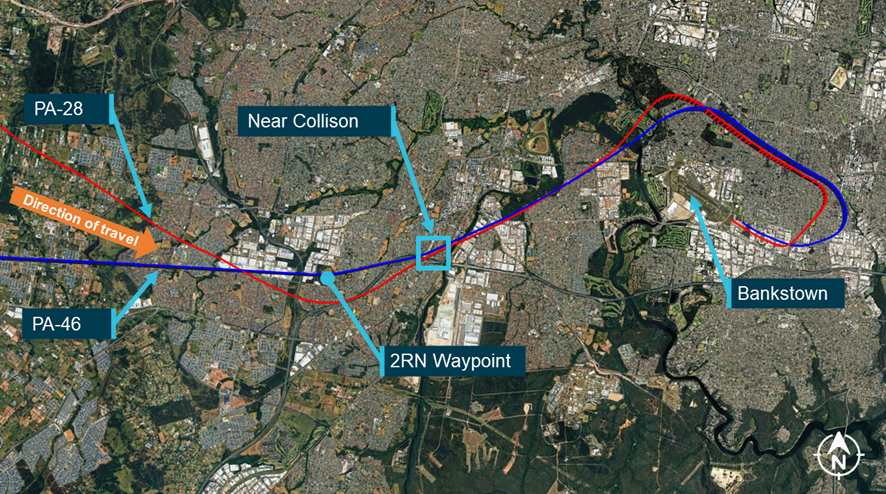

Passing slightly to the south of the reporting point (Figure 1) and tracking south‑east at 1,300 ft, the pilot of the PA‑28 made a radio call to Bankstown Tower to request clearance to enter the Bankstown airspace. They were instructed to join the crosswind leg of the circuit for runway 29R, maintaining 1,500 ft. The tower controller also advised the flight crew of traffic behind and to the left of their aircraft, which would pass to their left shortly. Acknowledging these instructions, the pilot of the PA‑28 turned left to take up a north‑easterly track and climbed slightly to 1,500 ft.

At around the same time, a Piper PA‑46 with one pilot and 2 passengers on board was also approaching Bankstown from the west, via the 2RN waypoint. Both the pilot and the front seat passenger held commercial pilot licences. The PA‑46 was operating under the instrument flight rules and was required to leave controlled airspace, enter Class G airspace and contact Bankstown Tower, to get a clearance to enter Class D airspace. As they left controlled airspace, the PA‑46 was advised by the Sydney Centre air traffic controller of traffic to the south‑east of the 2RN waypoint. The pilot visually identified an aircraft but having not heard the inbound call, incorrectly assessed it to be heading away from Bankstown and therefore did not consider there was a threat of collision.

Passing the inbound point on an easterly heading and descending through 2,400 ft, the PA‑46 was about 30 seconds behind the PA‑28 but above it and travelling 60 kt faster.

On switching to the Bankstown Tower frequency, the pilot of the PA‑46 heard the controller passing traffic information on their aircraft to the PA‑28. Consequently, when they made their inbound call, they advised that they were ’keeping an eye out for the Piper’. The controller instructed the PA‑46 to join crosswind for runway 29R and reiterated that there was traffic almost directly below them.

The pilot of the PA‑46 advised that they had sighted the PA‑28, however, while making a left turn to establish the aircraft on a crosswind track, they lost sight of the PA‑28. At around the same time, they noted they were high on the approach and commenced a rapid descent to reach the required height of 1,500 ft. The front seat passenger later advised that they had maintained visual contact with the PA‑28. The ATSB could not determine why this information was not communicated to the pilot at the time of the event.

The PA‑46 overtook the PA‑28 with very little separation, passing just to the left of the slower aircraft and at approximately the same altitude. Recorded ADS‑B data showed that the 2 aircraft came within about 80 m horizontally and about 25–30 ft[1] vertically at their closest point of separation.

The pilot of the PA‑46 reported that as they rolled out of the turn onto the crosswind leg of the circuit, they sighted the PA‑28 in their 2 o’clock[2] position and made an evasive turn to the left. The pilot of the PA‑28 reported that they had insufficient time to take any avoiding action.

Figure 1: Google Earth image of the flight paths

The PA-28 flight path is in red and the PA-46 flight path is in blue. Source: Google Earth with Flightradar24 data, annotated by the ATSB

Both aircraft continued their approaches and landed without further event. At the time of the near collision both aircraft were flying in non‑controlled airspace, and were about to enter the Bankstown Class D airspace.

Safety action

The operator of the PA‑46 reported that they often carry a commercially licenced pilot in the front passenger seat to act as a safety observer. Following the event, the operator has formalised a process for how the observer should communicate their observations and concerns to the pilot during flight.

Safety message

Operating into busy Class D airports such as Bankstown, requires pilots to maintain high levels of situational awareness, especially with respect to other traffic. A mixture of aircraft types of varying performance, converging around inbound reporting points, can create complex and challenging traffic scenarios. As such, these risks should be considered ahead of time.

While ATC will often provide information on other traffic, it is unable to provide positive separation. It remains the responsibility of the pilot to always maintain visual separation from other aircraft. If a pilot is unable to visually sight, or loses sight of, an aircraft they should immediately act to avoid a conflict.

In addition, descending rapidly in close proximity to an inbound reporting point, while not maintaining visual contact with traffic, significantly increases the risk of collision. It may be more appropriate to delay arrival at the reporting point, perhaps by flying an orbit, and descend to a more suitable height, to get a clear understanding of the traffic in the area, prior to approaching the inbound reporting point.

These issues were highlighted in an investigation conducted by the ATSB into a midair collision of 2 aircraft near the 2RN reporting point in 2008 (Midair collision Cessna Aircraft 152, VH‑FMG and Liberty Aerospace XL‑2, VH‑XLY, Casula, New South Wales, 18 December 2008 AO‑2008‑081).

Airservices Australia maintains several resources to assist pilots operating into busy Class D aerodromes, including specific tips for flying at Bankstown and a general guide to operating in Class D airspace.

About this report

Decisions regarding whether to conduct an investigation, and the scope of an investigation, are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation. For this occurrence, no investigation has been conducted and the ATSB did not verify the accuracy of the information. A brief description has been written using information supplied in the notification and any follow-up information in order to produce a short summary report, and allow for greater industry awareness of potential safety issues and possible safety actions.

[1] Position and altitude data from Flightradar24 includes some uncertainty.

[2] O’clock: the clock code is used to denote the direction of an aircraft or surface feature relative to the current heading of the observer’s aircraft, expressed in terms of position on an analogue clock face. Twelve o’clock is ahead while an aircraft observed abeam to the left would be said to be at 9 o’clock.