Executive summary

What happened

On 25 January 2024, at 0640 local time, a Raytheon Aircraft Company C90A aircraft, registered VH-JEO and operated by Goldfields Air Services, departed Kalgoorlie-Boulder Airport (Kalgoorlie), Western Australia (WA) on a commercial passenger transport flight to Warburton Airport, WA with one pilot and 2 passengers on board.

About half an hour into the flight, while operating in instrument meteorological conditions, an avionics failure resulted in the aircraft commencing an uncommanded turn to the right. In response, the pilot disengaged the autopilot and repositioned the aircraft back onto the correct heading. During this manoeuvring, altitude variations between −400 ft and +900 ft were recorded on ADS‑B tracking services.

Having observed the aircraft deviate laterally and vertically, the monitoring air traffic controller queried the pilot’s intentions several times. The combination of manually flying in IMC, troubleshooting and the interactions from ATC resulted in a high workload situation for the pilot.

The pilot elected to return to Kalgoorlie and the aircraft landed around 0800 local time.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB identified that the remote gyroscope failed, resulting in erroneous indications on the horizontal situation indicator while the aircraft was being operated with the autopilot engaged in heading mode. This resulted in a sustained, uncommanded right turn.

Contrary to the guidance in the pilot operating handbook, the pilot did not deselect the autopilot and continued to operate the autopilot in heading mode, which led to them experiencing high workload and sustained control issues.

Finally, although probably influenced by their focused attention on the malfunction, the pilot did not make a PAN PAN broadcast to ATC, reducing the opportunity for the controller to provide appropriate assistance.

What has been done as a result

Since the incident, the operator has:

- issued a notice to aircrew reminding pilots to disengage the autopilot and hand fly the aircraft any time there are failure modes indicated on the autopilot annunciator

- added training exercises relating to horizontal situation indicator and artificial horizon instrument failures in the line-oriented flight training phase of all pilots’ training.

Safety message

This incident highlights the value of aircraft system knowledge and pilot operating handbook familiarity in resolving malfunctions. Additionally, pilots should utilise all options to reduce their workload, including requesting assistance from air traffic services (ATS) when they recognise an emergency situation developing, to allow the appropriate support measures to be activated.

Controllers are reminded that a pilot in difficulty may not immediately alert ATS if they are disoriented or focused on maintaining aircraft control. If a controller assesses they may be able to assist, this should be communicated proactively.

The investigation

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report, and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

At 0640 local time on 25 January 2024, a Raytheon Aircraft Company C90A aircraft, registered VH-JEO and operated by Goldfields Air Services, departed Kalgoorlie-Boulder Airport (Kalgoorlie), Western Australia (WA) on a commercial passenger transport flight to Warburton Airport, WA (Figure 1). On board were the pilot and 2 passengers.

Figure 1: Flight track from Kalgoorlie to Warburton

Source: Google Earth overlaid with Flight Radar 24 data, annotated by ATSB

Around half an hour after departure, while maintaining flight level (FL) 210[1] and tracking to waypoint[2] KAPSU in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC)[3] with the autopilot engaged (altitude hold and navigation mode), the pilot requested and received a clearance from air traffic control (ATC) to divert left of track due to a storm ahead. The pilot changed the mode in the autopilot from navigation (tracking to waypoint KAPSU) to heading. They then set an initial target heading of around 350° using the heading bug[4] on the horizontal situation indicator (HSI)[5] (Figure 2), to track left of the storm before flying parallel to the original track to KAPSU. Once past the storm, the pilot changed the heading to around 030°, to re‑intercept the original track (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Horizontal situation indicator

Photo taken by the pilot during the flight showing the heading flag, the heading bug and the instrument indicating the aircraft heading was 027˚.

Source: The pilot, annotated by the ATSB

The aircraft commenced the right turn, but it continued to turn through the selected heading. In response, the pilot moved the heading bug left, but observed that the aircraft was very slow to respond.

Still in IMC and now heading towards the storm and associated severe turbulence that the pilot had diverted to avoid, the pilot completely disconnected the autopilot, and manually manoeuvred the aircraft away from the storm and towards the planned track. During the turn, uncommanded altitude variations between −400 ft and +900 ft were recorded on ADS‑B tracking services.

Figure 3: VH-JEO flight path

Source: Google Earth overlaid with Flight Radar 24 data, annotated by the ATSB

The controller observed the aircraft deviating from the cleared track and questioned the pilot as to their intentions. The pilot responded that they were ‘having some issues with the avionics’. The controller subsequently observed the aircraft descending and asked the pilot if they ‘were descending as well?’. The pilot then requested a block level from FL 210 to FL 100, which the controller advised they were unable to accommodate, due to class E airspace[6] below. The controller instead issued a descent clearance to FL 190, which the pilot acknowledged.

About a minute later the controller observed the aircraft climbing and asked the pilot ‘are you climbing?’ to which the pilot responded, ‘stand by’. Due to the presence of other aircraft, the controller advised that they needed the aircraft to maintain a level and asked the pilot what level they required. The pilot then advised they were descending back to FL 190. A minute later, the controller asked if the pilot would like vectors back to Kalgoorlie, which the pilot replied they were ‘having trouble with the autopilot in IMC’ and to ‘stand by’.

Once the aircraft returned to the planned track, the pilot re-engaged the autopilot and armed the navigation and altitude select mode. The navigation mode normally activated when the aircraft was within 90° of the planned track, but on this occasion it failed to engage and the aircraft recommenced an uncommanded turn to the right.

The pilot then detected that the HDG (heading) red flag was displayed on the HSI, indicating that the magnetic input to the HSI had failed or was unreliable. At this time, the flight director (FD) indicator bars disappeared from the electronic attitude direction indicator (ADI), and a red FD flag was also displayed, indicating that the flight director was no longer reliable.

At 0721, the controller asked if the pilot was intending to hold at their current location. The pilot advised that they were trying to resolve the issues, with a preference to continue to Warburton. Around 3 minutes later, unsure of the cause of the instrumentation issue, the pilot requested a return to Kalgoorlie, which was approved.

The pilot kept the autopilot engaged in heading mode and altitude select, with the intention of reducing their workload while operating in turbulence and IMC. By making continual inputs to the heading bug, the aircraft completed a turn onto the reciprocal track. The pilot assessed that the course deviation indicator on the HSI appeared to be working throughout the reciprocal turn to Kalgoorlie, as it still provided guidance to KAPSU. The pilot then selected the Kalgoorlie VOR[7] to provide directional reference on the left HSI and also monitored the right side HSI and the independent Garmin 600 GPS during the return flight. The aircraft’s system did not permit the right side HSI or Garmin 600 to be coupled to the autopilot (see the section titled Heading failure).

The aircraft landed at Kalgoorlie at 0802. A post-flight engineering inspection found that the left remote gyroscope had failed resulting in the left HSI providing erroneous indications.

Context

Pilot qualifications and experience

The pilot held a commercial pilot licence (aeroplane) with a Class 1 aviation medical certificate and had accrued 1,153 hours of aeronautical experience, 144 of which were on the C90A aircraft type. In May 2023, the pilot completed line-oriented flight training with the aircraft operator, which included knowledge and use of the autopilot.

Aircraft

VH-JEO was a Raytheon Aircraft C90A, twin‑engine turboprop aircraft with Pratt & Whitney PT6A‑21 engines. The aircraft was manufactured in the United States in 1997 and issued serial number LJ-1464. The aircraft was first registered in Australia in 2013. There were no outstanding maintenance items at the time of the incident.

Weather conditions

Data obtained from the Bureau of Meteorology showed that, at the time and location of the occurrence, icing and thunderstorms were forecast and present, with associated severe turbulence. The pilot reported that only light icing was present during the incident, which was appropriately managed by the aircraft’s anti‑icing systems and not considered a factor in the incident.

Heading failure

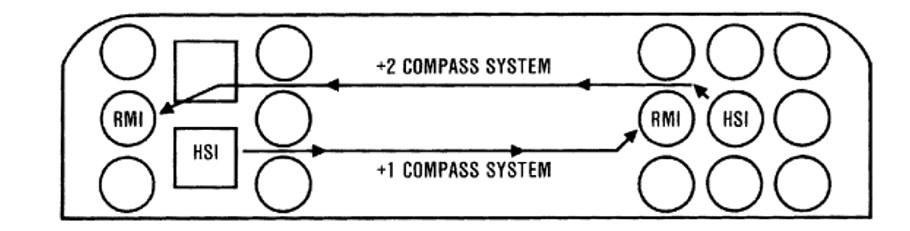

The C90A pilot operating handbook stated that, in the event of a heading failure on the HSI (indicated by a red HDG flag on the instrument), the pilot was to reference the instrument displaying compass no 2 data – either the opposite HSI or the same side RMI (Figure 4).

The C90A Collins autopilot fitted to the aircraft was unable to be coupled to the copilot’s (right) side instruments.

Figure 4: Compass systems on C90A

Source: King Air C90A/B Pilot training manual

Manufacturer guidance for flight director flag

The Collins FCS-65 autopilot guide stated that a flight director (FD) flag was generated when a system fault, such as a heading failure, warranted disengaging the autopilot. However, by the time the pilot identified the FD flag during this occurrence, they had already disengaged and re‑engaged the autopilot.

Collins Aerospace advised that several inputs to the autopilot computer monitor could activate the red FD flag on the ADI. Therefore, before continuing to use the ADI, if the red FD flag was in view there was a requirement to conduct an airborne self-test to determine the specific cause. The manufacturer further noted that this test is not widely practiced by pilots and was not included in the POH. As such, pilots were unlikely to be able to conduct the self‑test in flight and the POH recommended simply disengaging the autopilot if the red flag was present.

The United States National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) further advised that both the aircraft manufacturer and the autopilot manufacturer suggested that in the event of any autopilot malfunction (whether due to a failure of the autopilot or a system that feeds the autopilot) the autopilot should not be re-engaged. While there may be some input failure modes that would still allow modes of the autopilot to be useful, this would require the pilots to troubleshoot in flight, which they did not advise.

PAN PAN call

A ‘PAN PAN’ transmission is used to describe an urgent situation but one that does not require immediate assistance. Examples of such situations include instrument malfunctions and deviation from route or track in controlled airspace without a clearance.

According to the Manual of Air Traffic Services, when an air traffic controller receives a PAN PAN call from an aircraft, the controller will declare an alert phase.[8] Safety bulletin What happens when I declare an emergency, released by Airservices Australia, states that ATC may provide a range of support services including:

- passing information appropriate to the situation, but not overloading the pilot

- allocating a priority status

- allocating a discrete frequency (where available) to reduce distractions

- notifying the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (JRCC), appropriate aerodrome or other agency

- asking other aircraft in the vicinity to provide assistance.

Safety analysis

In-flight failure of the left remote gyroscope induced a slow, steady erroneous roll of the primary HSI display. As the autopilot was at the time operating in heading mode, the aircraft also began a constant turn to the right, attempting to follow the drifting heading bug.

In response to the observed aircraft turn, the pilot fully disengaged the autopilot (consistent with the guidance in the pilot operating handbook (POH) for an FD flag warning on the ADI) and manually manipulated the aircraft back onto the desired heading. During that manoeuvring, likely due to a combination of turbulence and manually flying in IMC, the aircraft experienced unintended altitude variations and the pilot was subjected to high workload.

While the pilot recognised the HSI was giving spurious readings, contrary to the guidance in the aircraft’s POH, they re‑engaged the autopilot (including heading mode) in an attempt to reduce their workload. Unfortunately, this had the opposite effect as the aircraft recommenced the uncommanded right turn, which the pilot countered by making constant adjustments to the heading bug.

In this instance, disengaging the autopilot and monitoring an alternate (secondary) compass system navigation aid (left RMI or right HSI) would have eliminated the uncommanded turn and enabled accurate instrument navigation.

The pilot reported that the interactions with ATC during this incident further increased workload and stress, but the pilot did not declare a PAN PAN to alert the controller to the extent of the instrument issues. While that omission was probably due to the pilot’s focused attention on the malfunction, it reduced the opportunity for the controller to provide appropriate assistance.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the instrument failure and control issues involving Raytheon Aircraft Company C90A, VH-JEO, 170 km north-east of Kalgoorlie-Boulder Airport, Western Australia on 25 January 2024.

Contributing factors

- The left remote gyroscope failed resulting in erroneous readings on the horizontal situation indicator while the aircraft was being operated with the autopilot engaged in heading mode, resulting in an uncommanded right turn.

- The pilot continued to use the autopilot in heading mode, contrary to the guidance in the pilot operating handbook, which led to them experiencing a higher workload and sustained control issues.

Other factors that increased risk

- The pilot did not make a PAN PAN broadcast to ATC, reducing the opportunity for the controller to provide appropriate assistance.

Safety actions

| Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. All of the directly involved parties are invited to provide submissions to this draft report. As part of that process, each organisation is asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they have carried out to reduce the risk associated with this type of occurrences in the future. The ATSB has so far been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence. |

Safety action by Goldfields Air Services

The aircraft operator:

Since the incident, the operator has:

- issued a notice to aircrew reminding pilots to disengage the autopilot and hand fly the aircraft any time there are failure modes indicated on the autopilot annunciator

- added training exercises relating to horizontal situation indicator and artificial horizon instrument failures in the line-oriented flight training phase of all pilots’ training.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- incident pilot

- air traffic control audio tapes

- chief engineer and head of flight operations of Goldfields Air

- recorded ADS-B data

- Bureau of Meteorology

References

King Air C90A/B pilot training manual, volume 2 aircraft systems, chapter 16, Flight safety international, 2002. P. 333

Manual of Air Traffic Services, version 67.1, 21 March 2024, Airservices Australia and Department of Defence, p.160

Collins FCS-65 Flight Control System (3rd edition) – pilot’s guide, Collins general aviation division/Rockwell international corporation, October 1989, p.26-27.

Raytheon Aircraft Beech King Air C90A Pilot’s Operating Handbook and FAA approved airplane flight manual supplement for the Collins FCS-65H automatic flight control system with Collins EFIS 84 electronic flight instrument system (EFIS), Raytheon aircraft company, 2002, p. 6.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- Airservices Australia

- incident pilot

- Goldfields Air Services

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Aircraft manufacturer

- Autopilot manufacturer

- National Transportation Safety Board.

Submissions were received from:

- Airservices Australia

- Goldfields Air Services

- Aircraft manufacturer

- Autopilot manufacturer

- National Transportation Safety Board.

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2024

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Flight level: at altitudes above 10,000 ft in Australia, an aircraft’s height above mean sea level is referred to as a flight level (FL). FL 210 equates to 21,000 ft.

[2] Waypoint: a specified geographical location used to define an area navigation route or the flight path of an aircraft employing area navigation.

[3] Instrument meteorological conditions (IMC): weather conditions that require pilots to fly primarily by reference to instruments, and therefore under instrument flight rules (IFR), rather than by outside visual reference. Typically, this means flying in cloud or limited visibility.

[4] Heading bug: a marker on the heading indicator that can be rotated to a specific heading for reference purposes, or to command an autopilot to fly that heading.

[5] Horizontal situation indicator (HSI): an instrument that combines magnetic heading indication and navigation guidance.

[6] Class E airspace: mid-level en route controlled airspace is open to both IFR and VFR aircraft. IFR flights are required to communicate with ATC and must request ATC clearance.

[7] Very high frequency omnidirectional range station (VOR): transmitters that support non-precision (lateral guidance only) approach and en route navigation.

[8] Alert phase: a situation where apprehension exists as to the safety of an aircraft and its occupants (this generally equates to a PAN PAN).