Investigation summary

What happened

On the morning of 28 July 2023, the pilot of a Piper PA-25 Pawnee, registered VH-SPA, was in the circuit to land on runway 06 at Caboolture Airfield, Queensland. Caboolture was a non-controlled aerodrome relying on self-separation by pilots. The Pawnee was a tow aircraft for the local gliding club, and had been towing gliders from runway 06 and had previously landed on the same runway. Several other aircraft had used the intersecting runway 11 during periods where runway 06 was not being used. The windsock indicated a light wind that varied in direction, favouring runway 11 or runway 06 approximately equally.

As the Pawnee was on final approach to land, a Jabiru J430, registered VH-EDJ, commenced a take-off roll on runway 11. Approximately 16 seconds later, just prior to the Pawnee touching down, a Cessna 172, registered VH-EVR, taxied across runway 06 without stopping or making a radio call. Seeing the Cessna, the Pawnee pilot elected to conduct a go-around to avoid a potential collision with it.

While the Jabiru pilot appeared to see the Pawnee late in the sequence and attempted to evade it, the 2 aircraft collided near the runway intersection at approximately 130 ft above ground level. The Jabiru’s right wing was damaged as a result, and the aircraft collided with terrain, fatally injuring the pilot and passenger. The Pawnee was damaged, but it landed safely and its pilot was uninjured.

What the ATSB found

While in the circuit, the Pawnee pilot had made positional radio calls, and a radio call stating their intention to land and hold short of the runway intersection. Based on the Jabiru pilot's apparent unawareness of the Pawnee until just before the collision, and most witnesses not recalling hearing any calls from the Jabiru throughout the event, it is likely that the Jabiru pilot could not transmit or hear radio calls for reasons that could not be determined. Likely unaware of the landing Pawnee’s presence, the Jabiru pilot commenced take-off on runway 11 while the Pawnee was on final approach to runway 06.

A stand of trees between the runways prevented the Pawnee and Jabiru pilots from being able to see one another’s aircraft once the Jabiru had taxied onto the runway heading. Not having heard any radio calls from the Jabiru, and unable to see it when on final approach to land, the Pawnee pilot was not aware that the Jabiru was taking off on runway 11.

The Cessna pilot had previously turned down the aircraft’s radio and not restored the volume prior to crossing runway 06. The pilot was therefore not aware of the Pawnee, and seeing the traffic on runway 11, was not expecting aircraft to be operating on runway 06.

The local gliding club regularly chose to operate on runway 06 for the first flights of the day, due to the runway’s proximity to the glider hangars, and sometimes used runway 06 later in the day when winds were light, including during periods of light traffic on runway 11/29. The use of an intersecting runway increased the collision risk as Caboolture was a non-controlled aerodrome relying on alerted see‑and‑avoid principles, exacerbated by the stand of trees blocking pilots’ sightlines.

Both the Jabiru and Pawnee pilots were familiar with the aerodrome and would have been aware of the line of sight limitations between the intersecting runways due to the stands of trees. However, the ATSB found that the aerodrome operator, the Caboolture Aero Club (CAC), did not effectively manage or inform pilots of the risk presented by trees and buildings around the airfield that prevented pilots from being able to see aircraft on intersecting runways and approach paths.

In this accident, it is likely that all 3 pilots had an understanding that runway 11 was in general use by aircraft, and therefore could be considered an active runway under applicable Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) guidance for pilots using non-controlled aerodromes. However, the Pawnee pilot reasonably considered runway 06 to be an active runway through their own use of it. The ATSB found that the CASA guidance did not clearly define the term ‘active runway’, and the definition could be interpreted in different ways. Further, the guidance did not provide practical advice to pilots using a secondary runway, and in some situations, it was contrary to existing regulations.

What has been done as a result

The CAC amended the Caboolture Airfield operations manual to state that no simultaneous runway operations are permitted under any circumstances. Pilots wanting to operate on a different runway must request this and receive confirmation or acknowledgement from all aircraft taxiing or in the circuit. The manual also now states that rolling (take-off) calls must be made. A submission has been made to include the procedure in Caboolture Airfield’s En Route Supplement Australia (ERSA) entry.

CASA advised that it is in the process of improving guidance material regarding the factors and safety issues which should be considered in determining runway use. To better align with the regulations and avoid confusion, CASA is removing all references of the term 'active' when associated with a runway. CASA will also expand the guidance provided in the Part 91 Acceptable Means of Compliance and Guidance Material to assist in the industry's understanding of this issue.

Safety message

This accident demonstrates that following the existing regulations, rules of the air and associated guidance does not completely overcome the risks inherent in using multiple runways concurrently. Pilots need to carefully consider the choice of runway, not only in context of which runway might be considered ‘active’ or ‘in use’ by others, but in terms of the specific type of risks that arise when any 2 or more aircraft are going to use different runways. These risks can be heightened or alleviated by a range of factors (for example, visual obstructions) that differ widely across operations and aerodromes, and can change over time.

More generally, self-separation using alerted see-and-avoid principles carries some risk in all situations. Pilots can mitigate this to some extent by:

- checking radio equipment for functionality prior to taxi

- establishing two-way communication with potentially conflicting aircraft as needed

- being mindful of the potential for radio communications to be missed or misinterpreted

- never assuming a runway or aerodrome is safe to use simply because no other aircraft are visible.

The ATSB SafetyWatch highlights the broad safety concerns that come out of our investigation findings and from the occurrence data reported to us by industry. One of the safety concerns is reducing the collision risk around non-towered airports.

The occurrence

Overview

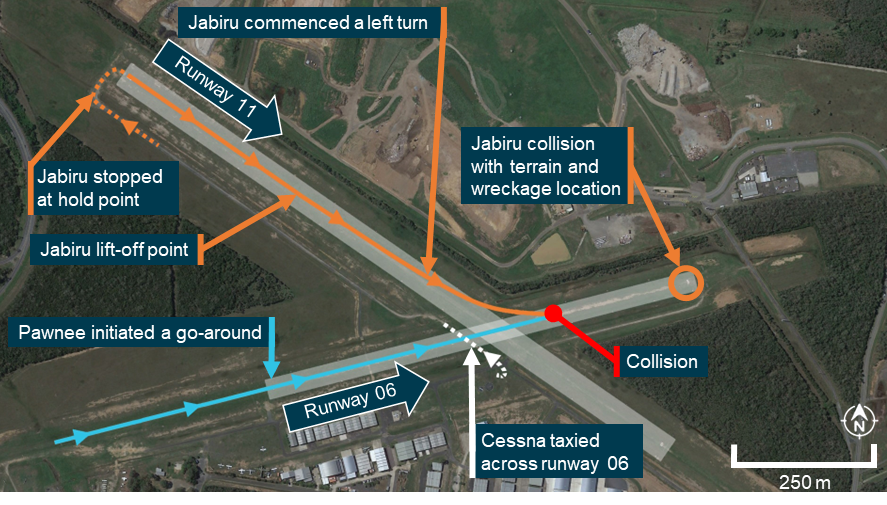

On the morning of 28 July 2023, the pilot of a single-seat Piper PA-25 Pawnee, registered VH‑SPA and operated by the Caboolture Gliding Club, was towing gliders from runway 06[1] at Caboolture Airfield, Queensland. At various times, other aircraft were using the intersecting runway 11 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Runway configuration at Caboolture Airfield

Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

As the Pawnee was on final approach to land after returning from the second glider tow, a Jabiru J430, registered VH-EDJ, with a pilot and passenger on board conducting a private flight to Dirranbandi Airport, Queensland, commenced a take-off roll on runway 11. About 16 seconds later, with the Pawnee about 200 m from touchdown, a Cessna 172, registered VH‑EVR, taxied across runway 06 without stopping or making a radio call. Seeing the Cessna, the Pawnee pilot elected to conduct a go‑around. The Pawnee began climbing at almost the same time as the Jabiru lifted off.

The 2 aircraft continued to climb on converging tracks. About 9 seconds later the Jabiru began a steep left turn in an apparent evasive manoeuvre but the 2 aircraft collided near the runway intersection, at about 130 ft above ground level.

The Jabiru’s right wing tip and aileron separated in the impact, and the aircraft collided with terrain, fatally injuring the pilot and passenger on board. The Pawnee was damaged, and the pilot returned to land without further incident.

First glider tow

At 1005 the pilot of the Pawnee took off from runway 06. It was a clear day with a 1–3 kt wind that varied between easterly and north-easterly. This was the Pawnee pilot’s first flight of the day, and the first time runway 06 had been used that day. All previous flights by other aircraft had operated on runway 11, which intersected runway 06.[2]

After the glider was released from aerotow,[3] the Pawnee pilot rejoined the circuit[4] for runway 06, and landed at 1017 without incident. Two radio calls related to this approach were recorded. The aircraft stopped short of the runway intersection, turned around and backtracked to the start of runway 06 – the runway threshold – to collect another glider.

Second glider tow and Pawnee rejoining the circuit

Caboolture Airfield was defined as an aircraft landing area (ALA), and was a non‑controlled aerodrome located within class G (non-controlled) airspace, and had a designated common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) on which pilots made positional broadcasts when operating within the vicinity of the airport.[5] Calls were not recorded at Caboolture Airfield, but some transmissions from aircraft in flight were recorded at Caloundra Airport, an airport about 32 km to the north that used the same CTAF frequency. The ATSB identified no recordings of radio transmissions from any aircraft on the ground at Caboolture around the time of the accident and some transmissions were only partially recorded (see Recorded data).

At 1022, the Pawnee pilot took off with another glider in tow. There was a radio recording of the Pawnee pilot responding at 1024 to a radio check request from another aircraft (the original call was not recorded). At about 1027, another aircraft took off from runway 11 after making a take-off radio call on CTAF that was heard by the Pawnee pilot, but not recorded.

Meanwhile, the pilot of a Jabiru J430, registered VH‑EDJ, had just commenced taxi towards runway 11. The Jabiru had been taxied directly from the hangars next to runway 06, turning north-west onto the taxiway parallel to the runway (and facing northwest) from 1027:25.[6]

The Pawnee pilot reported that after the glider was released from aerotow, with the tow rope still attached, they made a radio call to indicate they were descending towards Caboolture to the west of the airfield. This call was not recorded.

At the time, the wind was suitable for runway 06 and there was no other traffic in the circuit or on the ground that the Pawnee pilot considered as a potential threat to a safe landing on this runway. The Pawnee pilot then joined the crosswind leg for runway 06 and made the following radio call at 1028:09 (truncated in the recording):

Caboolture traffic sierra papa alpha Pawnee is heading crosswind to runway 06 Caboolture and…

The Pawnee pilot later reported that they also communicated with the aircraft that had just departed to arrange mutual separation. The Pawnee pilot then made the following radio call at 1029:07 on the downwind leg for runway 06:

Caboolture traffic sierra papa alpha is now late downwind runway 06 Caboolture

At 1029:40 the pilot then made a radio call for the base leg, which was truncated in the recording:

Caboolture traffic, sierra papa alpha is turning base runway…

Recorded data recovered from the Jabiru showed that at 1030:02, the pilot stopped at a hold point next to runway 11, facing north-east, perpendicular to the runway. At this time there were 2 other aircraft on the ground in the vicinity of the runway 11 threshold: one ahead of the Jabiru and one in the run-up bay. The Pawnee pilot recalled that while on the base leg, and focused on the potential for other traffic in the same circuit, they saw 2 aircraft in that area but did not identify what type they were and could not recall their exact positions.

The Pawnee pilot turned onto the final leg and made another radio call at 1030:19, truncated in the recording:

Caboolture traffic, sierra papa alpha is…

According to the Pawnee pilot and several witnesses who heard the transmissions, the Pawnee pilot announced that the aircraft would be landing on runway 06 and ‘holding short’, indicating that the aircraft would not be crossing the intersection with runway 11/29 during the landing. The ATSB could not determine whether the pilot made this statement during the base call or the final call.

The Pawnee pilot reported that they intended to hold short because they did not want to cross ‘another active runway’, aware of another aircraft about to use runway 11 as well as one that had just taken off. In this case the pilot was using the term ‘active runway’ to describe a runway that is, or could soon be, in use, and considered both runway 11 and runway 06 to be active (the latter through their own use of it). The Pawnee pilot was expecting the second departing aircraft not to commence take-off until the Pawnee pilot had reported that they stopped short of the runway intersection. In general, the Pawnee pilot reported they made the hold short call to advise other traffic of their intentions. They did not expect pilots to use the intersecting runway on the basis of the hold short call, and only expected pilots to use the intersecting runway after a ‘stopped short’, or ‘clear’ call was made. The pilot reported that they had done this (radioed an intention to land and hold short with other traffic using runway 11) on many other occasions and the other aircraft had always waited until the pilot had radioed that they had stopped short and were clear of all runways.

The aircraft ahead of the Jabiru departed at about 1030:26 following an associated radio call (which was heard by the Pawnee pilot but not recorded).

Pawnee continuing final approach and Jabiru commencing take-off

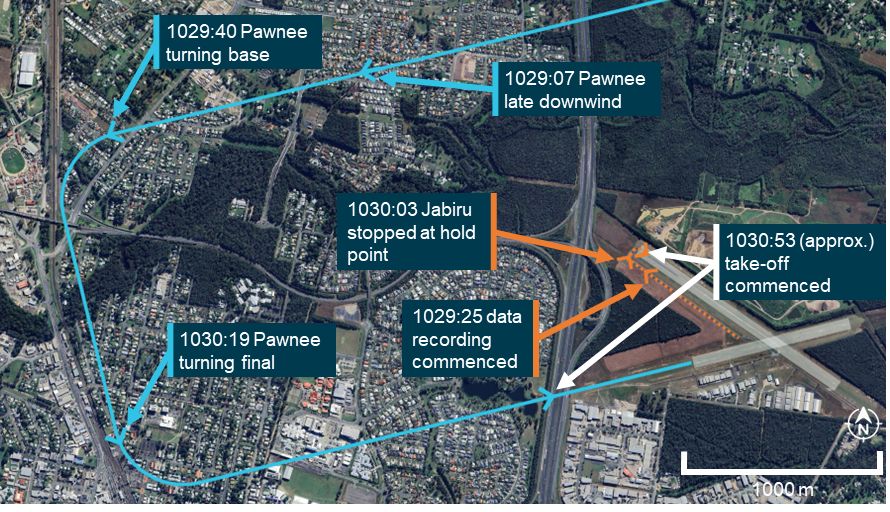

The subsequent sequence of events is illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2: Approximate tracks of the involved aircraft based on video recordings and recorded track data

Dotted lines indicate aircraft taxiing. Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

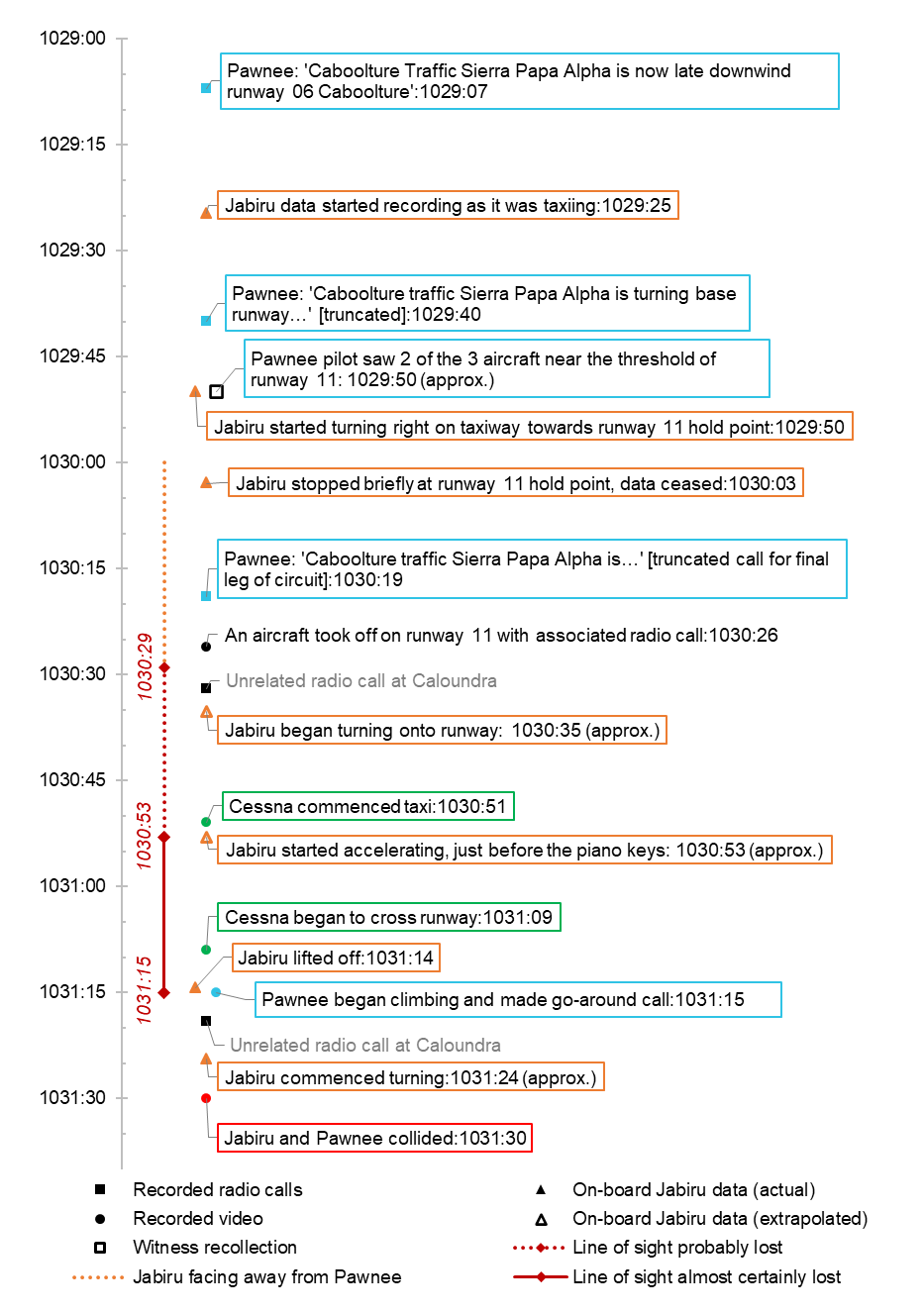

Figure 3: Sequence of events

Source: ATSB

An eyewitness stated that after waiting at the hold point, the Jabiru taxied onto the runway and immediately began the take-off roll. The recorded data was incomplete at this point, but ATSB analysis estimated that the Jabiru likely began to turn onto runway 11 at about 1030:35, establishing the runway heading a few seconds later. Take‑off would have commenced at about 1030:53. Two witnesses reported hearing the Jabiru pilot make a ‘rolling’ (take-off) call on runway 11, while 7 other witnesses, including the Pawnee pilot, stated that they did not remember hearing a rolling call. No witnesses recalled any other calls from the Jabiru.

At about the same time (1030:51), a Cessna 172, registered VH-EVR, had just commenced taxiing from a run-up bay south of the runway intersection. The aircraft was being operated by a solo student pilot who was intending to depart from runway 11. When the Cessna pilot first entered the aircraft, they heard the Pawnee making radio calls in the circuit. However, the Cessna pilot later reported having turned the radio volume down in order to concentrate on engine run-ups and pre-flight checks at the run‑up bay. As a result, the Cessna pilot did not hear the previous transmissions from the Pawnee pilot, and was not aware of it approaching runway 06 for landing. The Cessna pilot reported making a taxi call once checks were complete, and taxied onto the taxiway parallel to runway 11/29, heading towards the threshold of runway 11. At this point, the pilot realised the radio volume had not been restored and turned the volume back up.

At 1031:09, with the Pawnee about 200 m from touchdown on runway 06, the Cessna began to cross runway 06 ahead of the Pawnee. The Cessna pilot did not stop or make a radio call prior to crossing the runway. In interview, the Cessna pilot reported having been trained to stop and ‘clear’ a runway visually prior to crossing. However, the Cessna pilot had just seen an aircraft taking off from runway 11 and another (the Jabiru) lining up. With an understanding that aircraft were currently operating on runway 11, the Cessna pilot reported that they were therefore not expecting aircraft to be operating on runway 06/24, and did not look for any. In addition, due to the limited use of runway 06/24, the Cessna pilot did not always come to a complete stop before crossing.

As the Cessna began to cross the runway, the Pawnee pilot initiated a go-around,[7] unsure of the Cessna pilot’s intentions (for example, whether the Cessna was going to turn onto runway 06) and concerned about the potential for a ground collision. The Pawnee pilot reported making a radio call stating that they were going around, and said something like ‘watch out sunshine’. The order of these statements could not be determined. The radio call was not recorded, but 6 of the 10 witnesses with access to a radio reported hearing both the ‘going around’ and the ‘watch out sunshine’ parts of the call, and were relatively consistent in terms of the specific words used. Another 2 witnesses reported hearing the ‘watch out’ part of the call, but not the ‘going around’ part. At the same time, the Pawnee pilot applied full power, adopted a climb attitude and retracted one stage of flap.

Both aircraft climbing and collision

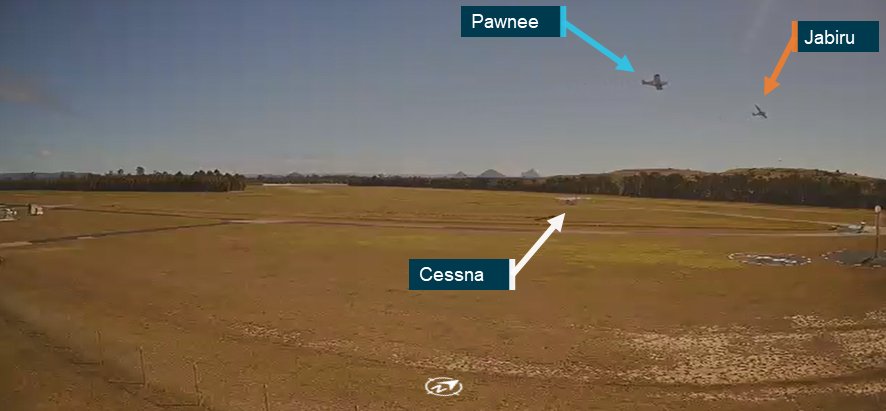

At 1031:15, the Pawnee began climbing while maintaining the runway 06 heading just as the Jabiru lifted off from runway 11 before the runway intersection. The Pawnee pilot was focusing on their climb rate, concerned about clearance between the trailing tow rope and the Cessna.[8] At about 1031:24, while the 2 aircraft were climbing at similar rates on converging tracks, the Jabiru pilot commenced a steep left turn (Figure 4). Given the steepness of the turn, and the low altitude, this was likely an attempt to avoid a collision. The Pawnee pilot reported not seeing the Jabiru until immediately after the impact, when they momentarily saw something behind the Pawnee’s left wing as they leant over to fully retract the flaps.

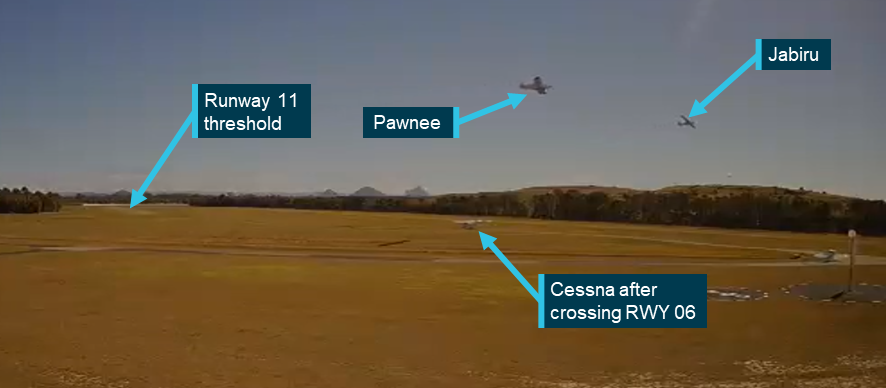

Figure 4: CCTV still image at 1031:06, from a camera south of the runway intersection, showing the 2 aircraft converging as the Jabiru turns left

Source: Caboolture Aero Club, annotated by the ATSB

At 1031:30, the 2 aircraft collided on similar tracks above runway 06, just north-east of the 06/11 intersection, at a height of about 130 ft. The leading edge of the Pawnee’s inboard left wing struck the Jabiru’s right wing at the outboard trailing edge, resulting in separation of the Jabiru’s right wing tip and part of the right aileron.

The Jabiru then rolled to the right while rapidly losing altitude. At 1031:38 it collided with terrain in a nose-down, right-wing-down attitude near the end of runway 06. The pilot and passenger were fatally injured.

The Pawnee sustained damage to its left wing in the collision but remained controllable and the pilot was uninjured.

After the collision the Pawnee pilot circled the airfield to direct first responders towards the accident site. The aircraft later landed on runway 11 without further incident.

Context

Pilot information

Jabiru VH-EDJ

The pilot of VH‑EDJ (the Jabiru) held an Air Transport Pilot Licence (aeroplane) and was a grade 2 flight instructor with multiple endorsements and ratings including as a flight instructor and for large passenger jets, having previously been an airline pilot. The pilot’s logbooks and other flight history could not be located. The pilot was reportedly experienced in general aviation and diligent with radio calls. The pilot had regularly flown at Caboolture Airfield, and held a class 2 aviation medical certificate that was valid until 30 October 2024. They were required to wear corrective lenses, but no other medical issues were listed on their licence. It could not be determined whether the pilot was using corrective lenses at the time of the accident. The ATSB could not obtain recent activity or sleep history for the pilot.

A post-mortem examination identified no significant pre-existing medical conditions (there was moderate heart disease that was considered ‘not significant enough to have caused a medical event’). Toxicology testing showed no alcohol, illicit drugs or relevant medications. Both the pilot and passenger had non-elevated levels of carbon monoxide.

Pawnee VH-SPA

The pilot of VH-SPA (the Pawnee) held a Private Pilot Licence (aeroplane) and held endorsements for glider operations and glider towing operations. The pilot was a level 3 instructor[9] with Gliding Australia, as well as a senior instructor and tow pilot examiner for Recreational Aviation Australia. They had operated as a tow pilot at Caboolture for over 20 years, and had performed 2,570 aerotow glider launches with a total flight experience of over 2,000 hours. The pilot held a class 2 aviation medical certificate that was valid until 17 July 2025. There were no relevant medical restrictions on the pilot’s licence, and they reported no medical issues or medications. The pilot also reported being well rested prior to the accident.

Cessna VH-EVR

The pilot of VH-EVR (the Cessna) was a student pilot conducting flying training at Caboolture. The pilot had commenced the process of attaining a Commercial Pilot Licence in January 2023 and did not yet hold a flight crew licence. The pilot had approximately 60 hours of flying experience. They attended Caboolture Airfield for flying training from Monday to Friday. The pilot was preparing to conduct their third solo navigation flight at the time of the occurrence. The pilot reported that runway 06/24 had been closed for approximately half of their training to date, having begun in January 2024.

Aircraft information

Jabiru VH-EDJ

The Jabiru J430 is a high-wing light aircraft. VH-EDJ had a single Jabiru 3300 piston engine and a ground-adjustable fibreglass propeller. It was constructed primarily by the pilot, first registered on 19 February 2019, and had recorded 283.7 hours total time in service at the time of the accident.

The aircraft was fitted with a Dynon SkyView SV-HDX1100 integrated touch screen avionics system, as well as an automatic dependent surveillance broadcast (ADS-B) transponder.[10] This model of transponder was capable of broadcasting the aircraft’s position (ADS-B OUT), but not receiving other positional broadcasts (ADS-B IN).

Pawnee VH-SPA

The Piper PA-25-235 Pawnee B is a low-wing single-engine aircraft. VH-SPA was powered by a Textron Lycoming O-540 piston engine with a fixed-pitch aluminium propeller. The aircraft was manufactured in 1969, and first registered in Australia in 1974. It had 10,181 hours total time in service, and had been operating as a tow aircraft at Caboolture Airfield since January 1997.

The aircraft was fitted with a basic analogue instrument suite. There was no ADS-B transponder fitted.

Wreckage and impact information

Overview

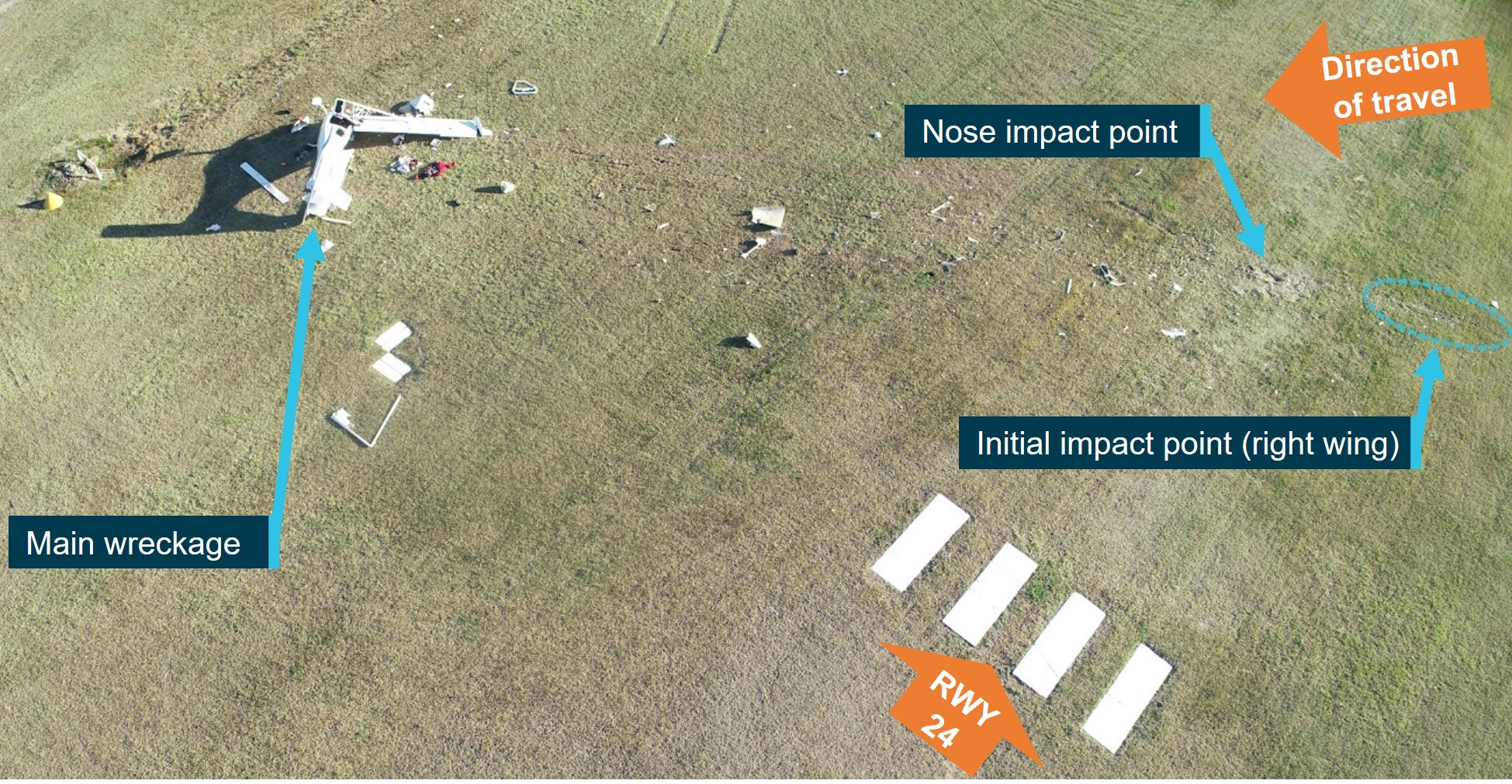

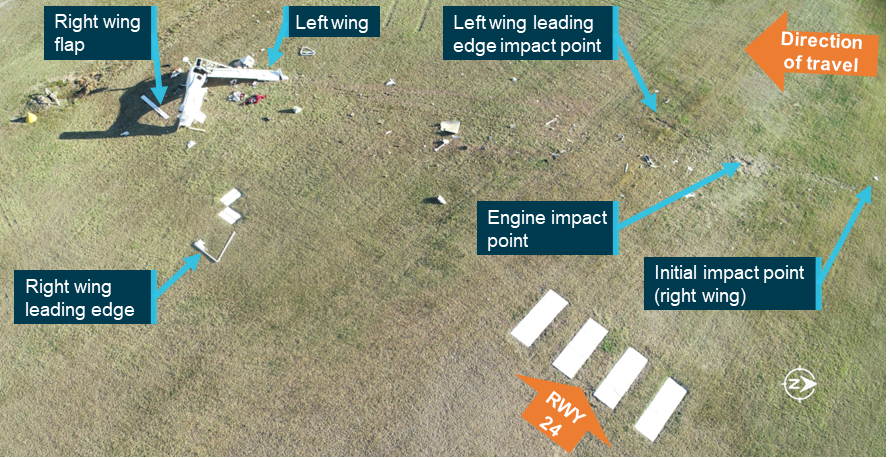

The ATSB conducted an onsite examination of the aircraft wreckage (Figure 5). The collision location and all aircraft components and wreckage were confined within the airfield. The Jabiru main wreckage site was near the threshold of runway 24, with a section of the Jabiru’s right aileron, right wing tip and associated wreckage located near the runway intersection.

Figure 5: Locations of aircraft and wreckage after the Pawnee had landed

Source: Queensland Police Service, annotated by the ATSB

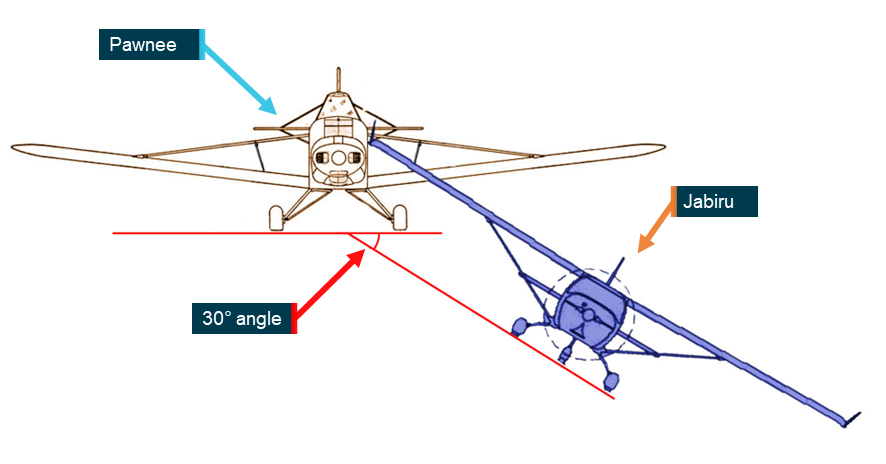

Based on the damage to each aircraft (described below), and the aileron and wing tip found near the runway intersection, the ATSB determined that the Pawnee’s left wing leading edge collided with the Jabiru’s right wing trailing edge. Damage signatures indicated that the relative angle between the 2 aircraft was about 30° in roll (Figure 6). There was no impact with the Pawnee’s propeller.

Figure 6: Approximate collision attitudes

This is a simplified diagram designed to illustrate the approximate difference in height and roll attitudes between the aircraft at the point of collision. The image does not reflect differences in pitch and yaw. Source: ATSB, Piper Aircraft and Jabiru Aircraft

Jabiru VH-EDJ

Accident site information

The Jabiru’s impact point was about 212 m beyond the separated wing tip and aileron (Figure 7). The right wing impacted the ground first, followed by the propeller and engine. The aircraft tumbled across runway 06/24 for about 42 m in a direction almost parallel to runway 11, coming to rest next to the runway threshold.

Figure 7: Jabiru wreckage trail

Source: ATSB

The rudder and elevator control surfaces were almost undamaged. They could be moved by hand after the accident, and the associated cables were continuous with all attaching hardware present. While the wing attachment points were heavily disrupted, damage to the control system appeared consistent with the midair collision and subsequent impact with terrain. Flaps were in the correct position for take-off.

The Jabiru’s engine mounts had fractured in the impact, with the control cables and fluid lines still intact. The wreckage site showed evidence of fuel spill from the wing tanks. Forward bending in the propeller blades indicated that the engine was driving the propellers at the time of impact. This, in conjunction with witness statements and video recordings indicated that the engine was producing power at the time of the accident.

There was no fire. First responders reported that both occupants were wearing shoulder and lap restraints.

Based on measurements of the ground scarring and the chord-wise symmetry of the right wing damage, it is likely that the Jabiru impacted terrain right wing first, in a nose‑down attitude of about 85°.

Based on the steep impact angle, the estimated speed, and disruption of the fuselage, the impact was not considered survivable.

Radio examination

A Microair M760-01 VHF transceiver radio was recovered from the Jabiru’s cockpit following the accident. The unit was heavily damaged and pulled away from the instrument panel, with the associated wiring still connected but damaged. The antenna and radio were still connected via a coaxial cable when the aircraft was inspected onsite, and the cable and antenna appeared undamaged. The ATSB retained the radio and some of the associated hardware (such as push-to-talk buttons) for subsequent testing. The cable and antenna were not retained. The headsets were damaged in the collision with terrain and therefore also not retained.

The radio turned on when power was applied during testing, and was selected on when recovered (a click is heard and felt at the beginning of the knob’s rotation to indicate on/off). The position of the volume knob prior to impact could not be determined as it may have moved during impact, recovery and transit. The radio was selectable between active and standby frequencies using a toggle switch, which was broken when found. The radio frequencies were set to 125.850 MHz (the CTAF frequency; see Radio communications at Caboolture Airfield) and 125.700 MHz (the area frequency). It was not possible to confirm which was selected as the active frequency prior to the collision.

Overall, the extent of damage to the radio and associated components precluded a determination of its probable functionality at the time of the accident.

Pawnee VH-SPA

The Pawnee remained intact after the collision (Figure 8). The tow rope stayed attached. Heavy impact damage occurred on the left wing leading edge, between about 0.25–1.2 metres from the wing-fuselage interface. Other impact damage was identified:

- on the wing strut, directly above the damage to the leading edge

- on a fuselage cowling panel located above the left wing

- on the left wing lower surface, including a small piece of fibre-reinforced plastic, caught between 2 panels, which appeared consistent with the skin of the Jabiru.

Figure 8: Damage to the Pawnee’s left wing

Source: ATSB

During the ATSB examination, the rudder, aileron, and elevator controls all responded appropriately to control inputs with a full range of movement without binding or restriction. All flight control surfaces were inspected for damage, and none was found. A basic visual inspection found no obvious issues with the engine or controls. There was no visible damage to the propeller. Based on the condition of the aircraft and the location of damage, and given that the aircraft landed safely, a detailed examination of the aircraft and engine was not conducted.

The radio and headset were tested by the ATSB and found to be serviceable in both transmit and receive modes. The frequency was set to the Caboolture Airfield CTAF frequency.

Operations at non-controlled aerodromes

Aircraft landing areas

Caboolture Airfield is an aircraft landing area (ALA). ALAs are non-controlled aerodromes that are not certified by CASA. They are unregulated facilities where pilots and operators are responsible for determining whether they are suitable for their use.

In general, CASA had no requirements or regulations that specified how ALAs were to be managed and operated.[11] The regulations and guidance provided to pilots regarding right of way, radio use and rules of the air were applicable at all non-controlled aerodromes, not just ALAs.

See-and-avoid

In non-controlled airspace, pilots rely on the use of the rules of the air and ‘see‑and‑avoid’ principles to maintain separation from other aircraft sharing the airspace.

An ‘alerted’ visual search is one where the pilot is alerted to another aircraft’s presence, typically through radio communications or aircraft-based alerting systems. Broadcasting on the CTAF to any other traffic in the vicinity of a non-controlled aerodrome is known as radio-alerted see-and-avoid and assists by supporting the pilot’s situational awareness and visual lookout for traffic with the expectation of visually acquiring the subject in a particular area.

Conversely, an ‘unalerted’ search is one where reliance is entirely on the pilot searching for, and sighting, another aircraft without prior knowledge of its presence. Unalerted see‑and‑avoid relies entirely on the pilot’s ability to sight other aircraft.

Issues associated with unalerted see-and-avoid have been detailed in the ATSB research report See and Avoid (Hobbs, 1991). The report stated:

See-and-avoid can be considered to involve a number of steps. First, and most obviously, the pilot must look outside the aircraft.

Second, the pilot must search the available visual field and detect objects of interest, most likely in peripheral vision.

Next, the object must be looked at directly to be identified as an aircraft. If the aircraft is identified as a collision threat, the pilot must decide what evasive action to take. Finally, the pilot must make the necessary control movements and allow the aircraft to respond.

Not only does the whole process take valuable time, but human factors at various stages in the process can reduce the chance that a threat aircraft will be seen and successfully evaded. These human factors are not ‘errors’ nor are they signs of ‘poor airmanship’. They are limitations of the human visual and information processing system which are present to various degrees in all pilots.

The United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) advisory circular AC 90-48D CHG 1 Pilots’ Role in Collision Avoidance indicated that it takes unalerted pilots around 12.5 seconds to sight an aircraft and react effectively to it (Table 1).

Table 1: Reaction times for airborne collision avoidance

| Event | Seconds |

| See object | 0.1 |

| Recognise aircraft | 1.0 |

| Become aware of collision course | 5.0 |

| Decision to turn left or right | 4.0 |

| Muscular reaction | 0.4 |

| Aircraft lag time | 2.0 |

| TOTAL | 12.5 |

Source: Federal Aviation Administration AC 90-48D CHG 1

The ATSB research report found that an alerted search is likely to be 8 times more effective than an unalerted search, as knowing where to look greatly increases the chances of sighting traffic. Similarly, an FAA research report (Andrews 1977) suggested that unalerted pilots may take 9 times longer to react than alerted pilots.

The ATSB research report Aircraft performance and cockpit visibility study supporting investigation into the midair collision involving VH-AEM and VH-JQF, near Mangalore Airport, Victoria on 19 February 2020 (AS-2022-001) contains more information on the human performance limitations of the see-and-avoid principle.

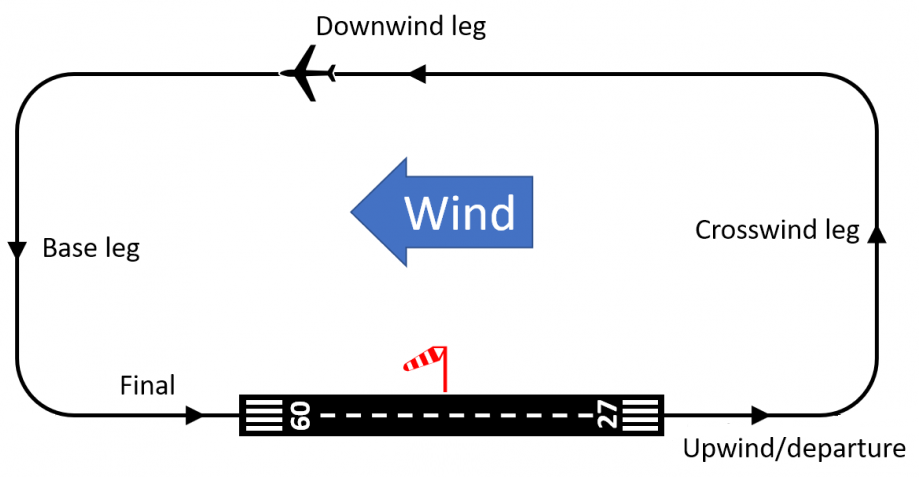

Standard circuit pattern

A circuit is the specified path to be flown by aircraft operating in the vicinity of an aerodrome (Figure 9). It comprises upwind, crosswind, downwind, base and final approach legs.

Figure 9: Standard left-hand circuit pattern

Source: SKYbrary, modified by the ATSB

Regulations and right of way

Part 91 of the Civil Aviation Safety Regulations 1998 (CASR) consolidates all of the general operating and flight rules for Australian aircraft and contains regulations detailing pilot responsibilities in relation to rules for the prevention of a collision, operating near other aircraft, right of way and operating in non-controlled airspace. These included but were not limited to the following regulations:

- 91.330: Right of way rules

- 91.335: Additional right of way rules

- 91.340: Right of way rules for take-off and landing

- 91.365: Taxiing or towing on movement area of aerodrome

- 91.370: Take-off or landing at non-controlled aerodrome—all aircraft

- 91.375: Operating on manoeuvring area, or in the vicinity, of non-controlled aerodrome—general requirements.

Right of way rules, which applied when there was a risk of collision between 2 aircraft, stated that when an aircraft is landing:

Any other aircraft (whether in flight or operating on the ground or water) must give way to the aircraft that is landing.

Regulations describing take-off and landing procedures stated that a pilot may not commence take-off until certain circumstances are met, including:

…if another aircraft is landing before the subject aircraft and is using a crossing runway—the other aircraft must have crossed, or must have stopped short of, the runway the subject aircraft is taking off from.

Regulation 91.370 prevented a pilot who is preparing to land from continuing an approach to land beyond the runway threshold if another aircraft is taking off on the same runway. These were not intended to take precedence over right of way rules, in the event of a collision risk. There was no specific regulation governing the continuation of a landing when another aircraft is taking off on a crossing runway.

When an aircraft is taxiing at an aerodrome:

the aircraft and any tow vehicle must give way…to an aircraft that is landing or on its final approach to land[12]

Land and hold short operations (LAHSO) are a set of internationally recognised procedures to allow a landing aircraft to land and hold short of a runway intersection while a crossing runway is simultaneously used by another aircraft. LAHSO is subject to stringent safety standards and training requirements, and applies only to controlled aerodromes (where aircraft in the area are directed by an air traffic controller). LAHSO procedures are therefore not applicable at a non-controlled aerodrome such as Caboolture.

In all other circumstances, including at non-controlled aerodromes, aircraft in flight or on the ground must give way to a landing aircraft as stated above.

When 2 aircraft are on converging headings at approximately the same altitude, the aircraft that has the other aircraft on its right must give way to the other aircraft.

Regulation 91.335 required that, when there is a risk of collision between 2 aircraft, the aircraft with right of way must maintain the same heading and speed until there is no longer a risk of collision. However, the regulation also stated that the avoidance of a collision takes precedence over compliance with these rules. Where an aircraft is required to give way to another aircraft, the aircraft must not be flown so that it passes ahead, or directly over, or under the other aircraft so close that there is a collision risk.

Advisory circulars

CASA published plain-language and explanatory guidance on the regulations in the form of advisory circulars (ACs) and other material. The following advisory circulars issued by CASA provided guidance to pilots operating at non-controlled aerodromes, including ALAs:

- AC 91-10 - Operations in the vicinity of non-controlled aerodromes

- AC 91-14 - Pilots’ responsibility for collision avoidance.

Regarding operations at non-controlled aerodromes, AC 91-14 noted that ‘rules of the air regarding right of way and rules for prevention of collisions must always be respected.’

The advisory circulars also outlined ‘alerted see-and-avoid’ principles and highlighted their importance for maintaining separation at non-controlled aerodromes. AC 91-14 gave guidance on visual searches and stressed the importance of improving a pilot’s situation awareness beyond reacting to what they can see using tools such as radio, ADS-B, and other electronic systems used for traffic avoidance. It stated:

The primary tool of alerted see-and-avoid that is common across aviation—from sport and recreational to air transport—is radio communication.

Carriage of radios

Part 91 of the CASR did not require aircraft to carry a radio when in the vicinity of uncertified aerodromes (such as Caboolture Airfield), but a radio was required in the vicinity of certified aerodromes (CASR 91.400).[13] Some aerodromes, including Caboolture, had a relevant instruction in the En Route Supplement Australia (ERSA) that required the carriage and use of a radio (see En Route Supplement Australia).

Mandatory and recommended radio calls

CASR 91.630 made certain radio calls (listed in the Part 91 Manual of Standards) mandatory for aircraft that are fitted with or carry a radio. The Part 91 Manual of Standards prescribed one type of mandatory broadcast at a non-controlled aerodrome, namely:[14]

When the pilot in command considers it reasonably necessary to broadcast to avoid the risk of a collision with another aircraft.

AC 91-10 reinforced this requirement and also stated:

Whenever pilots determine that there is a potential for traffic conflict, they should make radio broadcasts as necessary to avoid the risk of a collision or an Airprox event.

The Airservices Aeronautical Information Publication[15] stated:

In Class G [uncontrolled] airspace, pilots … should monitor the appropriate [radio] frequency and announce if in potential conflict. Pilots intercepting broadcasts from aircraft which are considered to be in potential conflict must acknowledge by transmitting own callsign and, as appropriate, aircraft type, position, actual level and intentions.

CASA recommended certain other broadcasts at a non-controlled aerodrome or dependent on traffic. AC 91-10 stated:

Pilots are reminded they are required to make all broadcasts necessary to avoid the risk of a collision with another aircraft as prescribed by Section 21.04 [Non-controlled aerodromes — prescribed broadcasts] of the Part 91 MOS. Table 5 [Recommended broadcasts in the vicinity of a non-controlled aerodrome] … contains the recommended broadcasts to achieve this requirement.

The recommended calls for non-controlled aerodromes included when a pilot:

- intends to take off

- is inbound to an aerodrome.

Calls that were recommended dependent on traffic included when:

- a pilot intends to enter a runway, including crossing a runway

- a pilot is joining a circuit

- the aircraft is clear of the active runway(s).

Limitations of radio communication

Positional broadcasts are a one-way communication, intended to provide a short and concise broadcast to minimise radio channel congestion. They do not imply receipt of information by other parties unless direct radio contact is made between stations to acknowledge the traffic, confirm intentions and, if required, discuss measures to provide deconfliction.

The VHF radio requires line of sight between both stations in order to function effectively. If an aircraft does not have a clear visual path direct to another in the vicinity, then the radio wave signal strength and clarity can be affected by obstacles. In some cases, terrain, vegetation or buildings can create areas that may shield or substantially reduce radio wave propagation and adversely affect broadcast signal strength and clarity.

AC 91-14 also advised:

Pilots should be mindful that transmitting information by radio does not guarantee receipt and complete understanding of that information. Many of the worst aviation accidents in history have their genesis in misunderstanding of radio calls, over-transmissions, or poor language/phraseology which undermined the value of the information being transmitted.

Without understanding and confirming the transmitted information, the potential for alerted see-and-avoid is reduced to the less safe situation of unalerted see-and-avoid.

AC 91-10 stated:

Pilots are reminded that although correct and informative radio calls play a critical role in ensuring collision avoidance in uncontrolled airspace, to ensure the safety of their aircraft they cannot assume that an absence of other radio calls means there are no nearby or conflicting aircraft…Pilots must continually look out for other aircraft, even when their broadcasts have generated no response.…

Pilots should not be hesitant to call and clarify another aircraft’s position and intentions if there is any uncertainty.

It is essential that pilots maintain a diligent lookout because other traffic may not be able to communicate by radio. For example, the other pilot may be tuned to the wrong frequency, selected the wrong radio, have a microphone failure, or have the volume turned down.

Runway use

Determination of ‘active runway’

The concept of an ‘active runway’ for non-controlled aerodromes was not defined in the regulations. The Part 91 Manual of Standards did not explicitly define the term, but referred to it in a paragraph about aircraft lighting (original emphasis):

[white strobe lights must be displayed] if the aircraft, on its way to the runway from which it will take off, or on its way from the runway on which it has landed, crosses any other runway that is in use for take-offs or landings (an active runway) — while the aircraft is crossing the active runway;

The same passage, slightly paraphrased, was also included in the CASR Part 91 Plain English Guide.[16] The following definition was provided as guidance in AC 91-10:

Active runway: The runway most closely aligned into the prevailing wind, or, in nil wind, or when predominantly all crosswind, it is the runway in use.

The CASA Visual Flight Rules Guide[17] stated:

Landings and take-offs should be made on the active runway or the runway most closely aligned into wind.

Use of multiple runways

The advisory circular AC 91-10 made the following statements regarding ‘active’ and ‘secondary’ runways (each in separate sections):

- Pilots should be vigilant when using a runway that is not the active runway to ensure that they do not create a hazard to aircraft using the active runway.

- Landings and take-offs should be made on the active runway or the runway most closely aligned into wind.

- If a secondary runway is being used (e.g. for crosswind or low-level circuits), pilots using the secondary runway should not impede the flow of traffic using the active runway.

The CASA Visual Flight Rules Guide stated:

If a secondary runway is being used, pilots using this secondary runway should avoid impeding the flow of traffic on the active runway.

Other information on the use of runways at non-controlled aerodromes

Other than as stated above, there were no regulations or guidance applicable to the use of non-controlled aerodromes about:

- determination of which runway is ‘active’, ‘secondary’ or ‘in use’ in the context of the relevant guidance

- the use of runways that were not the active runway

- stopping prior to entering a runway.

Caboolture Airfield information and procedures

Caboolture Airfield

As stated previously, Caboolture Airfield was a non-controlled aerodrome owned by the Queensland State Government and leased to the Caboolture Aero Club (CAC) for the aerodrome’s operation and management. It was an uncertified aerodrome, also known as an ALA. It was located about 3.5 km east of Caboolture, Queensland, with an elevation of 40 ft above mean sea level. Based on interviews with pilots familiar with Caboolture, the airfield sometimes had relatively high traffic volumes for an ALA, with a diverse traffic mix including light sport aircraft, weight shift aircraft, helicopters, gliders and warbirds. Several flight schools conducted both fixed-wing and helicopter flight training at the airfield.

Caboolture Airfield had 2 intersecting runways with magnetic orientations of 114°/294° (runway 11/29), and 065°/245° (runway 06/24). Their lengths were 1,129 m and 820 m respectively. Both runways were unsealed grass, except for a sealed portion at the beginning of runway 11.

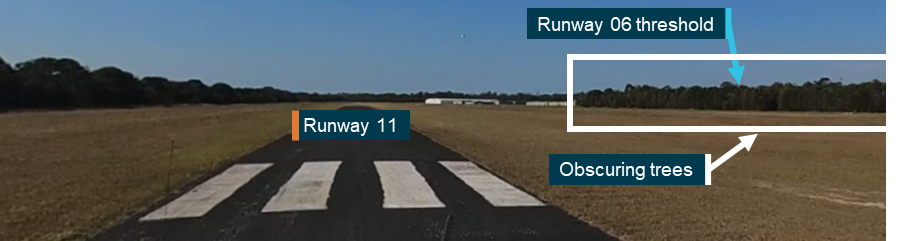

Two different stands of evergreen trees were established between the intersecting runways (Figure 10). The stand between the arrival ends of runway 06 and runway 11 was dense and it was not possible to see through it. Site measurements found that at its eastern-most point, the trees were at a height of about 9.5 m, but elsewhere, the trees were approximately 14 m high (the terrain itself is relatively flat). The northern border of the aerodrome was marked by a fence and a line of trees. Hangars, training schools and other administrative buildings stood to the south of the 2 runways. From the perspective of any of the 4 runway thresholds, the trees and buildings around Caboolture Airfield prevented pilots from being able to see either end of the intersecting runway (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

The ATSB estimated that the first 460 m of runway 11, and the first 180 m of runway 06, would not be visible from the other runway’s threshold. Visibility between the runways was significantly more affected if an aircraft was using the 250 m section prior to the runway 06 threshold (which was permitted for take-off only) (Figure 10, Figure 11, and Figure 12).

Figure 10: Obscured parts of the adjacent runway from the thresholds of runways 11 (orange) and 06 (blue) while at ground level

The shaded areas illustrate the areas that would not be visible from the threshold of the other runway. Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

Figure 11: Perspective from ground level at the threshold of runway 11

Source: ATSB

Figure 12: Perspective from ground level at the threshold of runway 06

Source: ATSB

Operations manual

Though not required to do so by regulation, the CAC maintained and published a Caboolture Airfield operations manual (available to the public on the club’s website), detailing procedures for pilots intending to operate at Caboolture Airfield. The most recent revision was 2.0, issued in March 2023. The manual did not take precedence over the CASR.

The Caboolture Airfield operations manual noted that traffic at the thresholds of runways 11 and 29 would not be visible if taking off before the threshold of runway 06 (pilots were permitted to commence take-off 250 m before the threshold of runway 06). It stated that aircraft towards the departure end of runway 06 might not be visible from before the landing threshold due to a crest in the runway.

The Caboolture Airfield operations manual stated (original emphasis):

Aircraft shall obey the standard Rule of the Air of ‘giving way to aircraft' established on final.

En Route Supplement Australia

Background

Information about controlled and non-controlled aerodromes around Australia was published in the En Route Supplement Australia (ERSA). The ERSA was part of the Airservices Australia AIP and published by Airservices Australia but the details for each aerodrome were provided by the aerodrome operator. CASR 139 required operators of certified aerodromes to ensure there was adequate aerodrome information in the ERSA. The types of information required included telephone numbers, runway specifications, lighting, visual aids, available ground services, local traffic regulations, special procedures and local precautions.

While there was no obligation for an uncertified aerodrome like Caboolture to have an ERSA entry, one had been submitted and maintained by CAC as the aerodrome operator. As a result, the CAC was considered to be an ‘aeronautical data originator’ under the regulations, and was therefore responsible for keeping the ERSA entry up to date.

ERSA information for Caboolture Airfield

The ERSA information for Caboolture Airfield noted the presence of gliding operations. It stated that trees may ‘encroach on Transitional Slopes gradients’; that is, may not meet obstacle clearance criteria that are mandated only for certified aerodromes. The effect of the trees on visibility between runways was not noted. The ERSA information advised visiting pilots to refer to the Caboolture Airfield operations manual synopsis available on the ‘aero club’ (CAC) website. This synopsis referred to a one-page appendix containing a quick reference handout with basic aerodrome and circuit information. This did not mention visibility between runways. However, as discussed in Guidance on the use of runways, the Caboolture Airfield operations manual noted visual obstructions elsewhere.

The ERSA information for Caboolture also stated: ‘Carriage and use of radio is required by the AD OPR [aerodrome operator].’ There was no regulatory requirement for pilots to follow specific aerodrome instructions of this nature that are in the ERSA, except with regard to circuit direction and at controlled aerodromes. However, according to AC 91‑10, such instructions may be considered a condition of use imposed by the aerodrome operator.

Relevant information for other aerodromes

An ATSB review of ERSA information (2024 data) identified 27 entries for non-controlled aerodromes, including 6 entries for uncertified aerodromes[18] that included information about visual obstructions between runways. ERSA entries for 4 uncertified aerodromes noted obstructions between intersecting runways or intersecting runway centrelines (where the runways themselves do not intersect but the approach and departure flight paths do). The other 2 entries were for visibility between both ends of the same runway.

The ATSB examined the relevant guidance associated with the visual obstructions. The entry for Casino required pilots to broadcast their intentions before operating on the runway, Great Lakes Airfield stated that a pilot must confirm that runways are clear prior to take-off or landing (without specifying the means to do so, but likely via radio), and 3 others required a radio to be carried and used (in a similar manner to the ERSA entry for Caboolture). None directly linked these requirements to the visual obstructions.

There were also 19 entries for certified, non-controlled aerodromes that included information about visual obstructions between runways or runway ends.[19] Of these, 9 entries stated that certain radio calls were to be considered mandatory, and all of these linked the requirement to the visual obstructions.

Guidance on the use of runways

Standard left circuits were specified at Caboolture, except for runway 29, which was a right circuit.

With regard to which runway was preferred for use, the Caboolture Airfield operations manual stated:

The active runway is the RWY [runway] most into wind and the runway being used by other aircraft at the time of your departure or inbound radio broadcast. Other runways may be used with radio notification to other traffic and with priority given to other aircraft already established in the circuit of the runway in use (the active runway) and with awareness of the Glider Launch point operations.

Regarding selection of runways by pilots, the manual stated:

The pilot in command of an aircraft has the authority to select the runway most suited to the performance and operational requirements for the safe operation of their aircraft however, with combined operations the active runway is usually the one required by aircraft with the poorest cross wind capability. These factors may be less important to pilots of fast, heavy aircraft who are more interested in the length of runway available for safe operations.

All operators at YCAB [Caboolture Airfield] are advised that any pilot selecting a runway other than the one which is clearly the ‘active’ runway (by virtue of into wind and minimum cross wind component and established circuit traffic), or that has been nominated as the ‘active’ runway by a radio information communication, then such pilot will lose all right of way privileges and shall conduct the landing or take-off procedure such as to give way to, and maintain separation from all other circuit traffic.

The manual also described the gliding operations at Caboolture, and outlined the concept of a ‘launch point’: a base of operations for unpowered aircraft such as gliders, centred around a camping trailer that acted as a mobile administrative office. The manual stated:

The launch point is usually established at a point on the airfield that minimises the time and effort required to retrieve the aircraft after landing and remain clear of the active runway so that the launch crew or parked aircraft do not impede the landing or taxiing aircraft.

The Caboolture Airfield operations manual did not state the gliding club’s general preference to use runway 06 (see Gliding club information).

Based on interviews with pilots at Caboolture, including members of the CAC, in light or variable wind conditions, there was a general preference for runway 11. There were 2 main reasons for this:

- Runway 11 was the only runway with a paved section just beyond the threshold. All other runways were unsealed grass.

- Although open at the time of the occurrence, runway 06/24 had been closed for resurfacing for a long period of time (see Closure of runway 06/24), so operators had developed a habit of simply not using it.

Radio communications at Caboolture Airfield

The common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) was 125.85 MHz, which was a frequency shared with Caloundra Airport, 32 km north-north-east of Caboolture.

The Caboolture Airfield operations manual stressed the importance of radio communication at Caboolture, and required that all aircraft – including gliders – carry a VHF radio tuned to 125.85 MHz. Regarding mandatory broadcasts, the manual required pilots to make an inbound call when 10 NM from the aerodrome, or at a known geographical feature. No other mandatory calls were listed, and the manual referred readers to the CASA advisory circular AC 91-10 (see Mandatory and recommended radio calls).

The Cessna pilot stated that they were trained to always make a radio call when crossing a runway, with the exception of runway 06/24 at Caboolture, where they were told not to make a call based on instructions from the CAC. An instructor at the Cessna pilot’s flying school reported telling students to generally avoid making a runway crossing call for runway 06/24 while the runway was closed, which they also recalled was based on a change to CAC procedures. The CAC did not have a record of a directive or change in policy regarding crossing calls. Several Caboolture operators interviewed by the ATSB advised that crossing calls had been a subject of ongoing discussion at the CAC. Some questioned the benefits of making a crossing call when there was no chance of a conflict with other traffic, arguing that such calls only added more crowding on an already congested radio frequency.

Closure of runway 06/24

Runway 06/24 was closed for resurfacing in December 2021, and reopened on 6 April 2023. Because Caboolture was an uncertified aerodrome, there was no regulatory requirement for hold point markings. However, runway hold point markings had been previously present on the taxiway across runway 06/24, but they were removed when the taxiway was repaved as part of the resurfacing (Figure 13). At the time of the occurrence, these lines had not been repainted. Hold point markings were still present on runway 11/29 (Figure 14).

Figure 13: Taxiway across runway 06/24 without hold point markings

Source: ATSB

Figure 14: Hold point markings at the threshold of runway 11

Source: ATSB

Gliding club information

General information

The Caboolture Gliding Club (CGC) was responsible for all unpowered glider operations conducted at Caboolture Airfield. Gliding operations were generally conducted on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays. The CGC headquarters was situated near the threshold of runway 06. The club also used a camping trailer as a mobile base of operations that could be towed to the launch point during gliding operations. The positioning of the base would depend on which runway the CGC deemed was most appropriate for gliding operations for a given period. All unpowered gliders were towed into the air using the Pawnee.

The process for towing gliders from runway 06 was as follows: a pilot would check for conflicting traffic on runway 11/29 via radio. If clear, the pilot would tow a glider into the air using the Pawnee, then release it from the tow rope after gaining sufficient altitude. The Pawnee pilot would then re‑join the circuit for runway 06 after it released, land while stopping short of the runway intersection, then backtrack to the launch point to pick up any other gliders for aerotow. The tow rope, which can be jettisoned in an emergency, would normally remain attached to the tow aircraft throughout.

Runway selection

Runway selection is important for towed glider take-offs as well as landings. The CGC’s documented standard operating procedures stated:

Before moving any equipment to the flight line the Duty Instructor will consult with the Tug [tow] Pilot to determine the runway to be used.

There was no other information within the procedures regarding runway selection and the procedures did not discuss potential visibility issues between runways. If the winds were favourable or sufficiently light, and traffic on runway 11/29 was light, it was common on the first flights of the day for the gliders to be towed into the air from runway 06. This prevented members from having to hand-tow the gliders long distances from the hangars to other runways. The gliders could then land on whichever runway had been selected for operation by the duty instructor in consultation with the tow pilot. The CGC would sometimes use runway 06 throughout the day, depending on the prevailing winds, including during periods when runway 11/29 was being used by other aircraft. Several members stated that if the traffic volume on the intersecting runway became too high, the tow pilot or the duty instructor would decide to move gliding operations to the runway being used by the rest of the traffic.

The CGC reported that winds, both at ground level and aloft, were an important consideration in runway selection, particularly for glider launches and landings. On the morning of the occurrence, prior to any gliding operation, CCTV footage of the windsock near the runway intersection showed that there was a light (easterly) wind favouring runways 11 and 06 approximately equally. There was enough variability in the wind that at any given time, the windsock could be seen favouring runway 11 or runway 06. The CGC had its own windsock near the end of runway 06. This was not visible on CCTV cameras but would often show a different wind direction to the other windsock. The CGC duty instructor and Pawnee pilot reported observing a north-easterly wind on the morning of the occurrence.

The duty instructor assessed that traffic on 11/29 was light, later estimating one movement every 15 minutes. Based on this, it was decided that the gliders could be safely towed from runway 06 for the first flights. According to the information they used, winds were forecast to increase down runway 06 throughout the day. It was therefore decided that gliding operations would continue on runway 06 while the conditions permitted it.

Regarding runway selection for landing prior to the accident, the Pawnee pilot stated that they selected runway 06 prior to joining the crosswind leg based on the wind conditions at the time (established by their view of the 2 windsocks at the airfield).

After the accident, the ATSB surveyed 18 pilots familiar with Caboolture Airfield (including the Pawnee and Cessna pilots) about a range of topics. The relevant responses were as follows:

- When asked about simultaneous intersecting runway operations at Caboolture, most pilots reported that the CGC had used runway 06, particularly for their first flights of the day while other traffic was operating on runway 11.

- Their assessment of how often intersecting runways were in use concurrently was roughly evenly distributed between ‘rare’ and ‘often’.

- None of the pilots believed it was common to hear tow pilots or others make radio calls to indicate they would be holding short of the runway intersection but some had heard that occur before with tow pilots.

- None of the pilots could recall a previous situation where a landing pilot made a hold short call and a second pilot took off while the first aircraft was still in the process of landing.

Recorded data

On-board recording

The Pawnee carried no flight data recording devices, and no automatic dependent surveillance broadcast (ADS-B) transponder. An ADS-B transponder was fitted to the Jabiru but the ATSB did not identify any recorded ADS-B data from the Jabiru during the accident flight.[20]

The Jabiru was fitted with a Dynon SkyView SV-HDX1100 avionics system. The system was capable of recording flight data installed in the cockpit. Flight data from the accident flight was recovered from the damaged device at the ATSB’s engineering facility in Canberra (Figure 15). The unit recorded the latter part of the Jabiru’s taxi towards the hold point for runway 11, turning onto the perpendicular taxiway from about 1029:49–1029:59, and the data terminated at 1030:03 when the Jabiru was at the hold point. This likely coincided with the Jabiru coming to a stop, as reported by a witness, while another aircraft was departing on runway 11. Assuming the Jabiru’s average taxi speed from the hold point to the runway was the same as the recorded segment, the ATSB estimated that the Jabiru would have been stopped for about 2 seconds before commencing taxi to the runway, starting to turn onto the runway heading at about 1030:35.

Figure 15: Flight data recovered from the Dynon SkyView system in the Jabiru

Source: Google Earth, ATSB

The GPS data recording was re-established at 1030:56, as the Jabiru was on the threshold markings of runway 11, rolling on the runway’s heading at 13 kt. Data showed the Jabiru accelerating and taking off, then initiating a left turn before colliding with the Pawnee at a height of approximately 130 ft.

Video recording

Video footage of the accident was recovered from a closed-circuit television (CCTV) at Caboolture Airfield. The system included several cameras on buildings south of the runway intersection, aimed in different directions. Due to the limits of resolution and distance, the CCTV did not capture movement of the Jabiru near the threshold of runway 11. The Cessna crossing runway 06, the Pawnee initiating a go-around, part of the Jabiru’s take-off and the collision itself were all visible on the recordings.

An example of the footage provided by the CCTV system is shown in Figure 16. Timestamps from the CCTV footage were adjusted to align with the times provided by the Jabiru’s recorded GPS data.

Figure 16: Still from a CCTV camera located to the south of the runway intersection

Source: Caboolture Aero Club, annotated by the ATSB

Using the CCTV recordings, the ATSB logged aircraft movements in the hour prior to the accident. From 0930 until the Pawnee took off with the first glider at approximately 1005, there were 15 movements on runway 11. While the Pawnee was airborne on the first flight, an additional aircraft landed on runway 11. The next movement was the Pawnee landing on runway 06, then taking off with the second glider at 1022.

A review of the CCTV recordings found that from 0930 until the occurrence, 9 other aircraft used the same taxiway as the Cessna to cross runway 06. Of these, 8 aircraft, including the Jabiru, did not stop before crossing.

CTAF recording

CTAF broadcasts were not recorded at Caboolture Airfield, nor were they required to be. Recorded broadcasts were recovered from Caloundra Airport, which shared the same CTAF frequency. Due to distance and line of sight limitations, radio calls on or near the ground at Caboolture were generally not recorded, and some calls from within the Caboolture Airfield circuit were only partially recorded. There may have been other radio calls from aircraft in the vicinity that were not recorded.

Recordings of radio calls made by the Pawnee pilot were assessed by the ATSB as being clear and readable. The recordings included some two-way communication, indicating that the Pawnee’s radio was functional for transmitting and receiving at the time. There was no evidence in the recording of the sound associated with simultaneous radio calls interfering with one another (often referred to as heterodyning), and no witnesses recalled hearing any such interference on the morning of the accident. Several pilots who flew at Caboolture stated that heterodyning was relatively common due to frequency congestion.

Aircraft visibility

Using CCTV footage and recorded GPS data from the Jabiru, the ATSB conducted an analysis to determine when the pilots of the Pawnee and Jabiru may have had an opportunity to see one another based on whether there was a line of sight between their relative locations and the location of trees around the airfield, and on the orientations of the 2 aircraft.

While taxiing towards the hold point near the threshold of runway 11 (facing north-east from about 1027:25 to about 1029:58), the Jabiru pilot might have been able to observe the Pawnee in the downwind or base legs of the (runway 06) circuit. Once the Jabiru had turned towards the hold point, the Pawnee was on or turning onto the base leg, putting it almost directly behind the Jabiru. Approximate positions of the Pawnee and Jabiru are shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17: Approximate positions of the Jabiru and Pawnee

Positions of the Pawnee were approximated based on CTAF transmissions, assuming a 1 NM wide circuit. The take-off time was estimated by extrapolating the Pawnee’s position backwards from when recorded data recommenced at 1030:56. Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

Without flight data for the Pawnee, and given the perspective of the camera, the Pawnee’s position and altitude could not be determined to a high degree of accuracy. For the purposes of estimating the Pawnee’s position, it was assumed that during the final approach the Pawnee maintained the same heading as runway 06, along the centreline, with a constant speed and a 3° angle of descent.

The Pawnee pilot later recalled seeing 2 aircraft near the threshold of runway 06 while the Pawnee was on the base leg of the circuit, one of which was about to take off. At this point, the Jabiru was taxiing towards the hold point near the threshold of runway 11, and a third aircraft was conducting engine run-ups in the nearby run-up bay. It could not be determined which 2 of the 3 aircraft the Pawnee pilot saw.

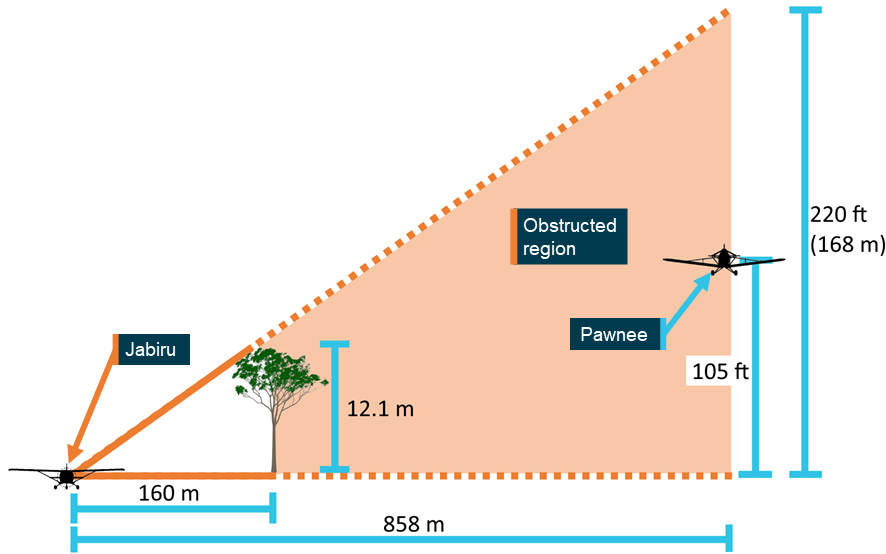

At the time the Jabiru had commenced its take-off roll, the Pawnee (on final approach) would have descended to about 105 ft and the trees would have obstructed line of sight from this point onwards. This was determined using a trigonometric calculation based on the assumptions described above (Figure 18). The trees would also have obscured line of sight from earlier than this, possibly from when the Pawnee descended below about 220 ft (a more precise estimate could not be made due to uncertainties about the Pawnee’s height and location on the downwind and base legs of the circuit). If the Pawnee’s descent rate had been constant throughout the final descent, it would have likely descended below 220 ft at about 1030:29, when the Jabiru was likely taxiing towards the runway.

Figure 18: Tree line obstruction height calculation when the Jabiru began its take-off roll

Not to scale. This calculation shows that the Jabiru and the Pawnee were not visible to one another when the Jabiru began rolling on runway 11. The Pawnee was estimated to be 105 ft high at this point. Assuming the Jabiru pilot’s view was 2 m above the ground, the 14.1-m trees blocked the Jabiru’s view up to 220 ft. Source: ATSB

By the time the Jabiru had turned onto the runway heading at about 1030, the Pawnee would have been behind the Jabiru and below the tree line from the perspective of the Jabiru pilot.

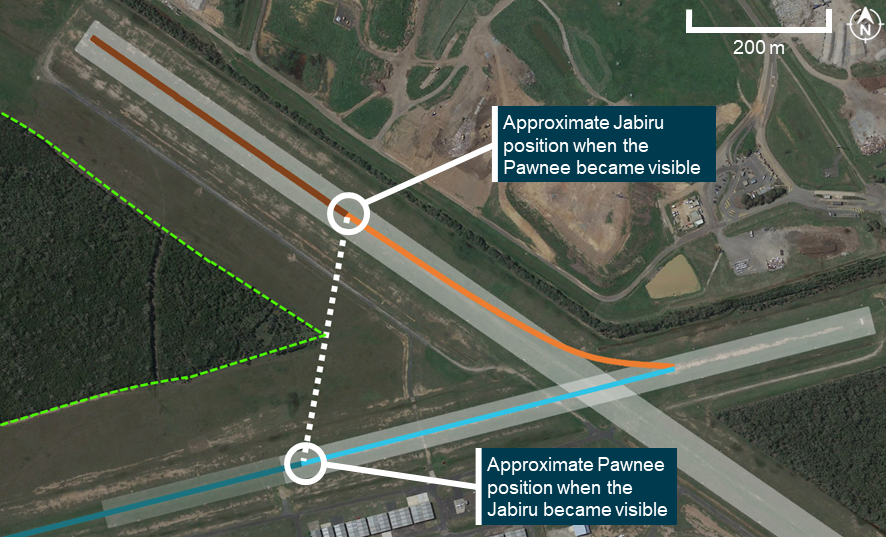

The trees would have prevented the 2 pilots from observing one another up until they were over their respective runways and had passed the end of the stand of trees, at approximately 1031:15. At this point, the Jabiru had only just lifted off the ground, and the Pawnee was just about to begin climbing, having almost touched down prior to commencing the go-around. The point in time that the line of sight was regained is illustrated in Figure 19. At this time, the Pawnee was about 75° to the right of the Jabiru’s heading, and the Jabiru was about 55° to the left of the Pawnee’s heading.

Figure 19: Sightlines between the 2 aircraft as they climbed from the aerodrome

Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

At this point, both of the aircraft would have been visible to each other, in the occupants’ peripheral vision if they were looking directly ahead. Objects in a person’s peripheral vision are more difficult to detect due to a number of factors including limitations from visual clutter and reduced visual acuity (Rosenholtz, 2016). During this period until the collision, there would have been very little relative movement of the aircraft in each field of view, making detection difficult.[21] Visual detection of objects is also strongly dependent on a person’s attention, head position and potential sight-blockers from the aircraft itself, such as a passenger, cockpit pillars, aircraft nose, wing struts or wings. The ATSB assessed that it was possible that the Pawnee’s structure blocked the pilot’s potential view of the Jabiru.

Related occurrences

Collisions or near collisions at non-controlled aerodromes

From 2013–2023 in Australia, there were 8 other reported collisions between 2 heavier‑than-air[22] aircraft at non-controlled aerodromes, where at least one of the aircraft involved was either in the aerodrome circuit, taking off, landing or taxiing.[23]

From 2013–2023 there were 118 reported near collisions[24] at non-controlled aerodromes. ATSB analysis indicated that, where relevant information was available, almost all of the incidents had 2 factors in common: a breakdown (or absence) of radio communication, and pilots not seeing each other’s aircraft. The following relevant types of communication issues were seen in the occurrences that were investigated:

- pilots misinterpreting radio communications

- one or both pilots not carrying a radio

- radio equipment not functioning properly

- radio transmissions not being heard

- interference from other transmissions.

Over the same time period, at non-controlled aerodromes, the ATSB occurrence database was searched for any collisions, near collisions, instances of separation issues[25] or runway incursions where keywords in the occurrence summary indicated that intersecting runways were involved. The search found:

- 1 collision (excluding this accident)

- 7 near collisions

- 19 instances of separation issues

- 2 runway incursions.

The collision was investigated by the ATSB (AO-2015-023) and involved 2 aircraft landing on different runways that collided at the runway intersection. Both aircraft sustained substantial damage and the pilots were not injured. The ATSB found that although there were no visual obstructions between the 2 runways, the pilots did not see one another. One pilot reported having an awareness of the other aircraft being in the vicinity, but not seeing it due to it blending into the terrain. The other pilot reported not expecting another aircraft to be landing on the other runway. Neither pilot was using their radio.

A more recent example was a near collision in June 2023 at Mildura Airport between a Piper PA‑28 and a Bombardier DHC-8 (Dash 8). An investigation report was published on the ATSB’s website (AO‑2023‑025). Mildura was a certified, non-controlled aerodrome, and both flight crews were preparing for take-off. The Dash 8 crew believed the PA-28 was at a different aerodrome because the PA-28 pilot misidentified a runway in a previous radio call. The PA-28 pilot knew the Dash 8 was at Mildura, but believed it was still taxiing. Airport buildings prevented the PA-28 pilot from seeing the Dash-8. The Dash 8 started its take-off roll on runway 09 as the PA-28 made a rolling call on the intersecting runway 36. The Dash 8 crew did not make a rolling call, believing there to be no traffic at the airport. The Dash 8 crossed ahead of the PA-28 at the runway intersection by about 600 m.

The ATSB investigated a related runway separation occurrence at Mildura, in September 2023 between a Dash 8 and a Lancair Super ES. Both aircraft were preparing to depart, from intersecting runways. Due to communication issues as well as the buildings and topography around the airport, neither of the flight crews were aware of the other aircraft prior to the Dash 8 taking off and the Lancair giving a rolling call. The pilot of a third aircraft (behind the Lancair) heard the Dash 8’s call and advised the Lancair to hold position while the Dash 8 departed, which they did. An investigation report was published on the ATSB’s website (AO‑2023‑050).

Other incidents at Caboolture Airfield

Not including this occurrence, there have been 21 occurrences at Caboolture Airfield involving aircraft separation between 2013 and 2023. Four of these occurrences were classified as near collisions, and the others were separation issues. Three of the occurrences at Caboolture involved intersecting runway operations that were counted in the above list. These occurrences were reported, but not investigated and are summarised below:

- In May 2021, the pilot of a Vans RV6 took avoiding action to pass below a Robinson R22 helicopter as both aircraft were departing on intersecting runways. The R22 crew reported not hearing radio calls from the RV6 (Near collision).

- In April 2021, while on approach, the pilot of an Aeropro 2k Eurofox reported horizontal separation concerns with a tow aircraft and glider that were climbing from an intersecting runway. The pilot did not hear any radio calls from the tow aircraft or glider. The tow aircraft was not identified (Separation issues).

- In May 2016, while landing on runway 30 (now runway 29), the crew of a Cessna 206 initiated a go-around to maintain separation with a Cessna 140 taking off from runway 24 (Separation issues).

Safety analysis

Introduction

While the Pawnee was on final approach to land on runway 06, the Jabiru pilot commenced a take-off on the intersecting runway 11. The Cessna taxied across runway 06 in front of the Pawnee, and the Pawnee pilot initiated a go-around to avoid a potential collision with it. While the Pawnee pilot did not see the Jabiru until immediately after the collision, the Jabiru pilot appeared to notice the Pawnee moments before the collision and turned, likely in an attempt to avoid the Pawnee. The leading edge of the Pawnee’s left wing struck the trailing edge of the Jabiru’s right wing. The Jabiru’s aileron and a section of outer wing separated as a result, and the Jabiru subsequently collided with terrain. This impact was not survivable, and the pilot and passenger were fatally injured. The Pawnee remained controllable and landed safely shortly after.

This analysis will discuss the events and conditions that led to the midair collision and/or increased safety risk.

Pilot awareness

Jabiru pilot’s awareness

The Jabiru pilot’s decision to take off as the Pawnee was on final approach indicated that either the Jabiru pilot was not aware of the Pawnee at all when commencing take-off, or had some awareness but elected to take off anyway.

As established in the Context section of this report (see Aircraft visibility), trees between the intersecting runways meant the Pawnee would not have been visible from the Jabiru for a significant part of the sequence of events, including the period leading up to the commencement of the take-off. The Jabiru pilot may have had an opportunity to see and/or hear the Pawnee during preparation for flight or taxi. However, even if the Jabiru pilot only had a general awareness of the Pawnee’s presence through seeing it earlier (such as when in the circuit), it would have been difficult to accurately project its flight path and predict its position.

The Jabiru pilot’s level of situation awareness was therefore highly dependent on whether they heard any or all of the Pawnee pilot’s radio calls. The Pawnee pilot’s account, statements from various witnesses and common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) recordings from Caloundra Airport were all consistent (accounting for witness recollection) to determine that the Pawnee pilot made at least 4 radio calls indicating their position in the circuit for runway 06.