What happened

On the morning of 15 December 2015, a SOCATA TBM 700 aircraft, registered VH-YZZ (YZZ), departed Gold Coast Airport, Queensland for Lake Macquarie Airport, New South Wales. On board were the pilot and one passenger.

The flight to Lake Macquarie was uneventful and the pilot reported feeling well.

SOCATA TBM 700, VH-YZZ

Source: Martin Eadie/Airliners.net

Having not previously landed at Lake Macquarie, the pilot overflew the aerodrome, at approximately 1,500 ft above ground level, to confirm the airfield layout. After the overflight, the pilot joined the upwind leg and commenced a left circuit for runway 07 (Figure 1). The aircraft was configured for landing during this time and, when on final, the approach speed was set to 80 kt.

Figure 1: Indicative flight path of YZZ overflying Lake Macquarie Airport prior to joining the downwind and final legs of the approach to runway 07

Source: Google maps – modified by ATSB

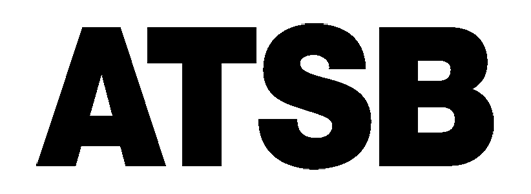

When YZZ was on short final, the pilot began to feel ‘woozy’ and, shortly after, lost consciousness. Closed circuit television footage showed the aircraft descended onto the runway and bounced before impacting the runway in a nose-low attitude to the left of runway centreline. The nose-low impact collapsed the nose gear and caused the forward section of the aircraft to strike the runway, bending all four propeller blades. It was at this time that the pilot regained consciousness, approximately 5 to 10 seconds after losing consciousness. The aircraft then skidded on the runway before veering to the right, and onto the grass (Figure 2). The aircraft eventually stopped on the grass area next to the runway (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Final approach path of YZZ to runway 07 with the approximate positions the aircraft first impacted the runway, bounced, the second impact and the approximate path YZZ skidded along, and across, the runway before coming to a stop on the grass

Source: Google maps – modified by ATSB

Figure 3: YZZ post-accident showing the damage to the forward section of the aircraft as a result of the nose gear collapse and skidding on the ground

Source: Phil Hearne/Fairfax syndication

After YZZ had come to a stop, the pilot and the passenger detected a burning smell and made an emergency egress from the aircraft. Once they were safely clear of the aircraft, the pilot saw that there was no fire and that the smell was from the nose gear being jammed under the fuselage and skidding on the runway surface. The pilot then re-entered the aircraft and shut down the engine to ensure that the risk of fire was eliminated. Neither the pilot nor the passenger were injured in the accident, however the aircraft was substantially damaged.

Aircraft systems

All systems on the aircraft were functioning normally. There was no fault evident with any system that could have contributed to the pilot’s loss of consciousness.

Pilot comments

The pilot stated they were well rested, had eaten prior to and during flight and were appropriately hydrated. The pilot reported that they had no previous loss of consciousness events, nor were there any extra pressures or distractions that may have affected them during the flight.

Medical tests and monitoring after the accident found that the loss of consciousness was due to a previously undiagnosed heart condition.

Safety message

The health of flight crew is vitally important for the safe operation of aircraft. Ultimately, all flight crew are responsible for monitoring their own health and wellbeing. Any deterioration in health that may affect the performance of flight crew should be taken seriously.

While in this instance, the pilot had no indication of a health concern before to the event, it is important for pilots to assess their fitness to fly prior to flight. The following checklist provides a quick reference. A description of aeromedical factors is available in the US Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge.

Source: US Federal Aviation Administration

In February 2016, the ATSB released a research report into pilot incapacitation occurrences between 2010 and 2014. The report provides valuable insight into pilot incapacitation occurrences in high-capacity air transport, low-capacity air transport and general aviation.

The report highlights how pilot incapacitation can occur in any operation type, albeit rarely. Of interest, the research found that around 75 per cent of the incapacitation occurrences happened in high-capacity air transport operations (about 1 in every 34,000 flights). With the main causes being gastrointestinal illness and laser strikes. Low-capacity air transport and general aviation had fewer occurrences with a wider variation of causes of pilot incapacitation. These ranged from environmental causes, such as hypoxia, to medical conditions, such as heart attack.

Importantly, the report reminds pilots in general aviation, to assess their fitness prior to flight. Assessment of fitness includes being aware of any illness or external pressures they may be experiencing.

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 47

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |