What happened

On 20 July 2014, the pilot of a Cessna 182L aircraft, registered VH-TRS, was conducting a private flight in the local area surrounding the rural township of Burrumbuttock, NSW. The aircraft was observed by witnesses to be travelling at low altitude in a westerly direction toward the township. As the aircraft was flown above a paddock on the outskirts of the town, the aircraft struck wires from a high voltage powerline. The aircraft subsequently rolled inverted and impacted terrain. The wreckage came to rest a short distance from the Farmers Inn. The pilot was fatally injured, and the aircraft was destroyed.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found no evidence of any engine or airframe defect that may have contributed to the accident. The pilot did not hold any approval to conduct low flying and had not received training in the identification of hazards or in the operating techniques for flight close to the ground. There was no operational reason identified for the pilot to have been flying at such a low altitude on the day of the accident. The evidence also indicated that the pilot had a history of unauthorized low flying.

The pilot was reported to be in good health with no issues that might have affected his ability to fly an aircraft. Despite this, the postmortem medical examination revealed a pre-existing medical condition that could have resulted in pilot incapacitation. While it is possible that the pilot may have had a medical incapacitation event immediately prior to the accident, the aircraft was being operated in a manner consistent with previous flights undertaken by the pilot and at a level that provided little margin for error should such an event have been experienced.

Safety message

This accident highlights the importance to pilots of not flying below the regulated thresholds of 1,000 ft AGL for flight overpopulated areas and 500 ft for flight over non-populated areas. Pilots who fly below this height without appropriate training and an operational reason to do so are exposing themselves and any passengers that may be on board to an increased risk of striking hazards, such as electrical power lines, many of which are difficult to see from the cockpit of an aircraft in flight.

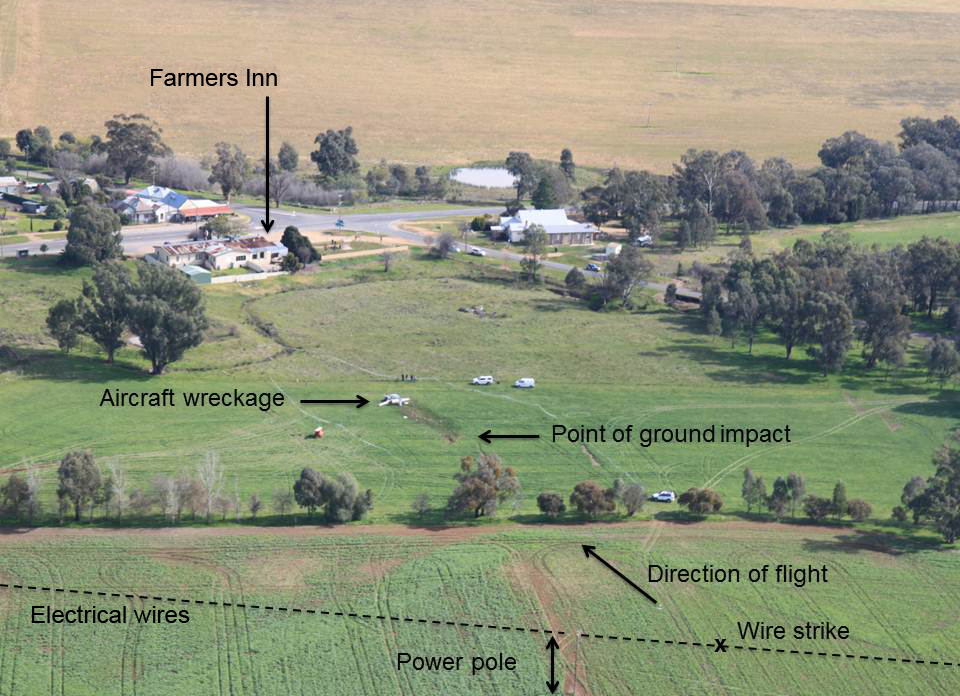

Accident site VH-TRS

Source: ATSB

At about 1700 Eastern Standard Time[1] on 20 July 2014, a Cessna 182L aircraft, registered VH-TRS, departed from the pilot’s own airstrip for a private flight under visual flight rules[2]. The pilot was appropriately qualified and endorsed on the type of aircraft. Family members and friends of the pilot reported that he regularly flew on weekends around the Burrumbuttock area. His pilot logbook indicated that the flights were generally short in duration of less than one hour.

About 30 minutes into the flight the aircraft was observed to be flying at a low altitude above the ground in a westerly direction toward Burrumbuttock. At 1733, the aircraft struck two energised electrical wires from a powerline in a paddock that bordered the town. The aircraft continued on for a short distance before it impacted terrain in a steep nose-down inverted attitude, stopping short of the Burrumbuttock ‘Farmers Inn’ hotel (Figure 1).

Patrons within the inn were alerted to the accident and immediately exited the establishment to investigate. A number of people ran to the wreckage to render assistance to the pilot. Despite the presence of leaking fuel, one of the patrons crawled into the aircraft where it was confirmed the pilot had sustained fatal injuries.

Figure 1: The accident site at Burrumbuttock

Source: ATSB

Witness descriptions

There were a number of witnesses identified during the investigation that had either spoken with the pilot early on the day of the accident, who saw the aircraft flying later that afternoon, or who had seen the accident.

Those who saw or heard the aircraft on the day of the accident reported nothing abnormal in its operation. It was noted that it was not unusual to see the aircraft flying quite late in the day around the local area. Two witnesses reported seeing the aircraft flying quite low as it approached the town.

Immediately prior to the accident, the aircraft was observed approaching the town at low altitude. The aircraft appeared to lose height as it banked left, in the direction of the Farmers. It struck the powerlines shortly afterwards. The aircraft subsequently became unstable and impacted terrain a short distance from the hotel.

__________

Pilot information

The pilot had lived and worked in the Burrumbuttock region for around 20 years. He had obtained a private pilot aeroplane license in January 1999 and subsequently gained experience in a range of single- and twin-engine aircraft. Toward the end of 1999, the pilot had attained an Aerobatics and Spinning endorsement and in 2005 had also qualified to fly at night under visual meteorological conditions.[3][4]

The pilot’s logbook showed that he had last undergone and successfully completed a biennial flight review in April 2014. He did not hold a low-level flying endorsement and there was no record of him undergoing low-level flying training. He had accumulated a total of 1,033.6 flying hours, approximately half of which was spent at the controls of the accident aircraft.

The pilot regularly flew the aircraft around the local area and was known to fly over the Farmers Inn, within the Burrumbuttock township, on occasion during weekend flights. A witness to one of these previous flights recalled that the aircraft had passed over the inn, tracking in a westerly direction and that he thought the pilot had maintained a safe altitude.

The pilot occasionally flew with a family friend, also an experienced aviator and one who regarded the accident pilot as someone who flew well and in control. Most of the accident pilot’s flying was around regional New South Wales and Victoria.

Medical and pathological information

The pilot’s last aviation medical assessment was in October 2010, at which time there was no identified medical condition and/or medication which may have affected his ability to operate an aircraft. Family and friends of the pilot reported that he was fit and well rested in the period leading up to the accident.

A post-mortem examination was conducted and the autopsy report stated that the injuries sustained to the pilot were consistent with that of a high energy aircraft accident. Toxicological screening did not reveal the presence of any drugs or toxins.

The autopsy report also stated that narrowing and damage of a major coronary artery to the pilot’s heart was identified. There was an area of plaque haemorrhage and fibrin deposition within the artery that is typically seen as an immediate precursor to a heart attack. The report summarised that, due to abnormalities in the blood vessel, it was possible that the pilot became incapacitated prior to the crash.

Aircraft information

The aircraft was manufactured in the United States in 1968 by the Cessna Aircraft Corporation as a model 182L. The aircraft was a four-seat, single-engine, high-wing configuration with a conventional tricycle undercarriage. The engine fitted was a Teledyne-Continental Motors six-cylinder reciprocating piston variety with a McCauley two-blade, constant speed propeller. The aircraft was certified for visual flight rules (VFR) and VFR Night; where flying during the day or night was permitted under visual meteorological conditions.

The engine fitted to the aircraft had last been overhauled in October 2000. The engine logbooks indicated that it had last been serviced in September 2013, 1,065.5 total hours of engine operation since that last overhaul. All servicing requirements were up to date and the next scheduled service was due on 13 September 2014.

Examination of the daily inspection and service sheet records for the aircraft showed the last complete entry was logged the day before the accident flight at 7,930.8 hours. An incomplete entry on 20 July 2014 indicated that the daily certification inspection had been completed by the pilot. There were no reported problems with the aircraft from family members and persons who were familiar with the aircraft.

Wreckage and impact information

Accident site

A survey of the accident site showed that the aircraft travelled along the flight path for 195 m after contacting the powerlines, before impacting terrain in an inverted, nose-down attitude of approximately 500 - 600. Upon impact with the terrain, the aircraft then slid forward an additional 30 m. These characteristics, in particular, the extended distance travelled from the location of the wire strike, indicated that the aircraft had been travelling with significant forward speed at the time.

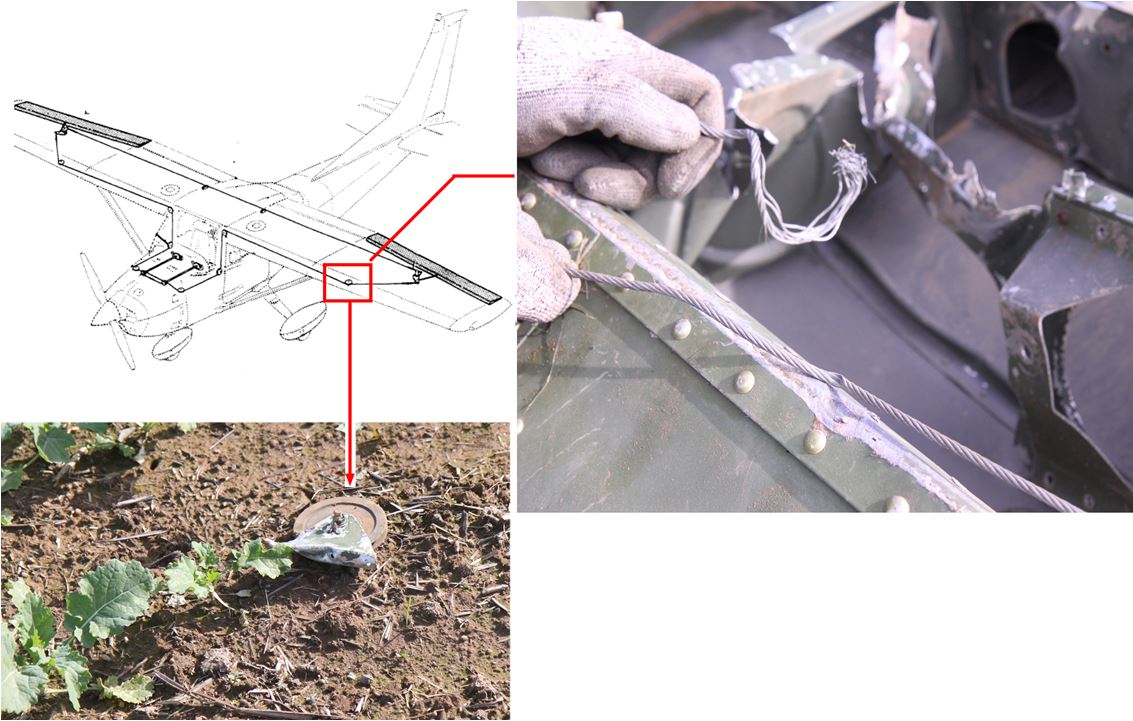

Debris along the flight path in advance of the powerline included items from the left wing, comprising a segment of leading-edge skin, plastic pieces from the landing lights and a guide pulley from the aileron controls.

Aircraft structure

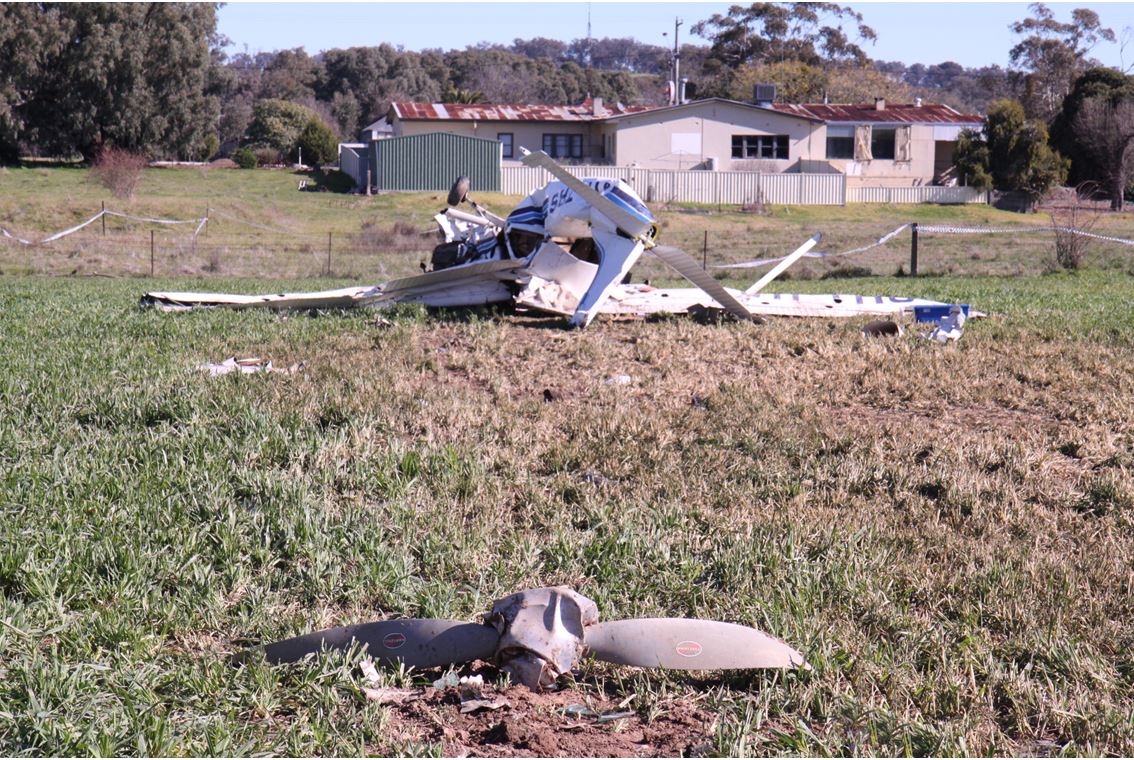

The aircraft structure had sustained severe damage from ground impact forces (Figure 2). Both wings were compressed and the tail section had buckled midway along its length. Upon contact with the ground, the nose and front section of the aircraft took the majority of the impact loads, breaking the engine mounts and compromising the survivable cockpit space. The pilot’s seatbelt assembly was locked and secure.

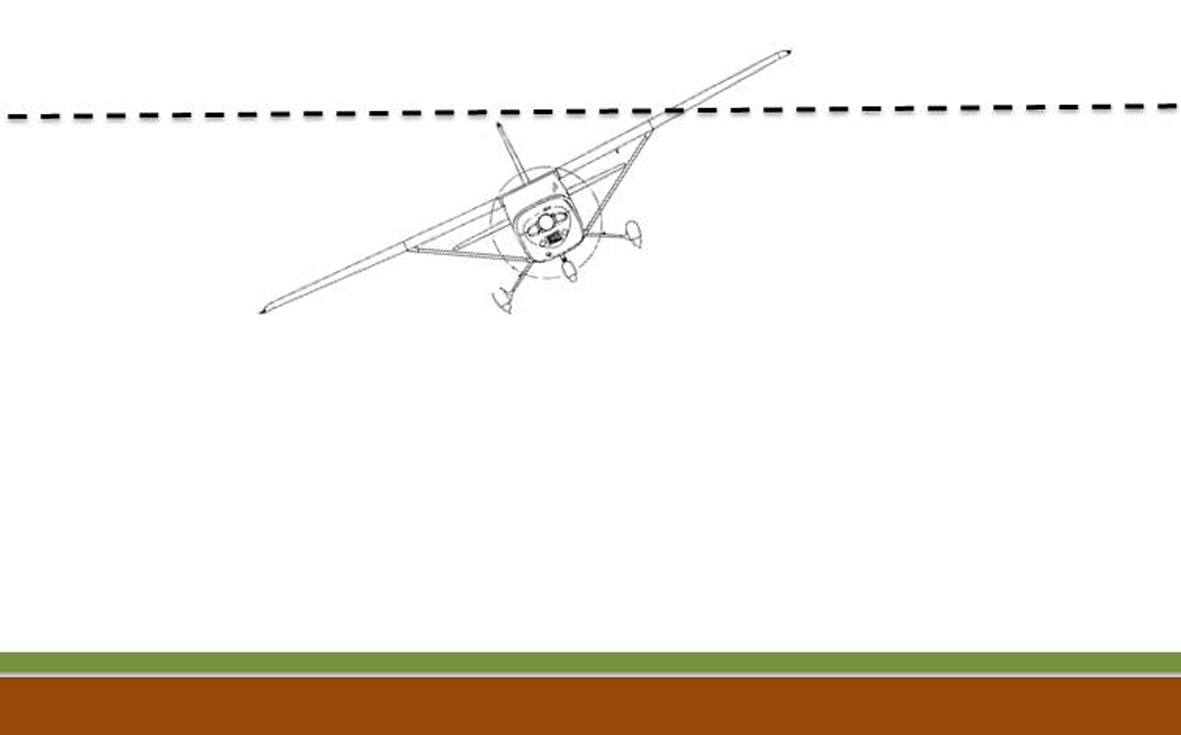

A significant quantity of fuel had leaked from the damaged wing fuel tanks. The front spar from the left wing displayed saw marks and tearing that was consistent with striking the powerline. The marks commenced at the strut-to-spar connection and their general orientation indicated that the aircraft was probably right-wing low at the time of the wire strike (Figure 3).

All of the primary structures and controls were accounted at the accident site. With the exception of the left aileron cable, flight control continuity was established and no pre-impact defects were identified. The left-wing aileron cable had fractured in overstress coincident with the strut-to-front spar connection (Figure 4).

A small sample of fuel was recovered from the fuel sump drain. The colour and smell of the fuel was consistent with aviation gasoline. Testing on-site showed that water was not present in the fuel sample.

Figure 2: The aircraft impacted terrain near the Farmers Inn hotel. The aircraft was inverted at impact and the propeller separated from the engine

Source: ATSB

Figure 3: Illustration showing the likely aircraft orientation at the time of striking the powerline

Source: Illustration by Cessna Aircraft Corporation (modified by ATSB)

Figure 4: The aircraft’s left wing leading edge structure including the aileron guide pulley and cable, was damaged from contact with the powerline

Source: Illustration by Cessna Aircraft Corporation (modified by ATSB); photographs ATSB

Engine and propeller

Analysis of propeller damage can provide evidence of the operational state of an aircraft’s engine at the time of any collision with terrain. In this instance, the engine was severely disrupted during the accident sequence and the propeller had separated from the crankshaft and was embedded in soil a few metres forward of the initial point of ground impact. Both blades from the propeller exhibited chordwise scoring and a degree of bending and twist that was consistent with being operated under significant torque at the time of the accident (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Propeller slash marks (arrowed)

Source: ATSB

Recorded data and instrument examination

Garmin GPS

A severely damaged Garmin AERA 500 GPS navigation unit was recovered from within the wreckage at the accident site. The ATSB applied forensic techniques to remove and then interrogate the internal memory module from the GPS.

Data from the previous 4 months of flying, including the accident flight, was able to be recovered. Parameters recorded by the GPS were: latitude, longitude, altitude and time. Analysis of the data revealed the following:

- The pilot had routinely conducted low-level flying in the local area throughout the previous 4 months, as well as on the day of the accident flight.

- The pilot had flown over the Burrumbuttock ‘Farmers Inn’ on many occasions. On 6 July 2014, 2 weeks prior to the accident, the aircraft was flown over the Inn at approximately 150 ft above ground level. The aircraft then continued to descend over the powerline (struck by the aircraft in this accident) and manoeuvre at very low altitude.

- The accident flight data (Figure 6) captured a number of low-altitude and aerobatic manoeuvres, including an extremely low-level pass into a quarry, located north-east of Burrumbuttock. Previous flight data showed that the pilot had conducted that manoeuvre previously.

- The final recorded GPS track point for the accident flight was written at 1731, approximately 2 minutes prior to the accident. The aircraft altitude at that time was approximately 420 ft above ground level. The ATSB was unable to determine why the GPS ceased recording data at that point.

Figure 6: Accident flight path noting that the final 2 minutes of data was unable to be recovered

Image Source: Google Earth TM, edited by ATSB

Cockpit instruments

Laboratory examination of the cockpit instruments that were recovered from the aircraft wreckage was conducted at the ATSB’s facilities in Canberra. This type of examination may reveal fine details on an instrument face, or its internal mechanism, that may assist an accident investigation gain further information about the aircraft at the time of the accident. In this instance, no additional evidence was able to be derived.

Weather and environment

The Bureau of Metrology forecast at the time of the accident were for overcast conditions, with a light north-westerly wind of up to 3 kt (6 km/h). Witnesses reported weather conditions, including wind strength that were consistent with the forecast.

Sunset on 20 July 2014 for Burrumbuttock was calculated to have occurred at 1720 and last light[5] was at 1748. The accident occurred at 1733. The position of the sun at the time of the impact with the powerline was calculated to be below the level of the horizon.[6] Under overcast conditions and with the sun having set, the pilot’s ability to observe the fine detail of the electrical wires was likely to have been significantly diminished.

Minimum height requirements

Regulation 157 of the Civil Aviation Regulations 1988 outlines the requirements for conducting low flying. It states:

(1) The pilot in command of an aircraft must not fly the aircraft over:

(a) any city, town or populous area at a height lower than 1,000 feet; or

(b) any other area at a height lower than 500 feet.

The above requirements did not apply if weather conditions made it essential for the pilot to fly at a lower altitude. The regulation also did not apply if the aircraft was engaged in approved low flying operations, the aircraft was taking off or landing, or was engaged in the dropping of articles as part of a search and rescue operation. There was no evidence in the pilot’s documentation to indicate that the pilot was issued with a low-flying approval or permission from CASA. There was similarly no evidence to indicate that the pilot was engaged in any approved low-flying operations.

Powerlines

The powerline struck by the aircraft was not required to be marked in accordance with Australian Standard AS 3891.1 - 2008 Air navigation - Cables and their supporting structures - Marking and safety requirements. The electrical supply organisation reported that the section of powerline impacted by the aircraft consisted of a series of wooden poles, each supporting dual, three-strand, interwoven steel wire conductors (Figure 7). Installation drawings for the section of powerline showed that the poles had been erected and the electrical wires strung in 1994. The powerline was energised at the time of the accident and supplied electricity to a number of households in the immediate area. Each pole in the series was separated by distance of about 300 m.

The aircraft’s impact with the powerline dislodged both electrical wire conductors from their insulated tie-off points atop the cross-arm of one of the poles. One of the wires was severed from the impact and a large current fault was recorded at 1733:08 by the company’s electrical system. On-site measurements showed the point of impact to be 30 m to the nearest wooden pole and the wire height at the point of impact was estimated to be 9.5 m above the ground.

Emergency landing

It was known by some members of the local community that an emergency landing strip had existed in a relatively flat farm paddock that bordered the eastern edge of the Burrumbuttock town. The land owner of the paddock reported that the most recent aircraft to have landed on that strip was at least 20 years prior and that any remnants of the strip were probably concealed by crop.

An aerial survey flight was conducted during the on-site phase of the investigation which showed that the paddock was being used for cropping and pasture. No identifying markers or features could be observed that might otherwise indicate the location of such a strip in that paddock and the circumstances of the accident do not indicate that the pilot was seeking to conduct a forced landing.

Figure 7: The powerline (electrical wires arrowed) looking back along the flight path. A piece of the leading edge skin from the left wing is also shown

Source: ATSB

Wire strikes – an avoidable accident

The ATSB has investigated numerous accidents involving wire strikes from previous years. The investigations generally found that the pilot was involved in low flying for no identified operational reason and, in many of the occurrences, was more than likely aware of the presence of wires.

Between 1999 and 2008, there were 147 fatal accidents reported to the ATSB involving aerial work, flying training, private, business, sport and recreational flying in Australia. Of those fatal accidents, at least six were associated with unauthorised and unnecessary low flying; that is, flying lower than 1,000 ft (for a populous area) or 500 ft (for any other area) above ground.

In March 2013, the ATSB published an education series based on avoidable accidents. The first of the avoidable accident series was focused on accidents involving unnecessary and unauthorised low flying:

ATSB Avoidable Accidents No. 1 ‘Low-level flying’

Recognising the risks and hazards of low-level flying, CASA requires pilots to receive special training and endorsements before they can legally conduct low-level flying. In the accidents examined, many of the pilots did not have low-level training or an endorsement to do so, and none had a legitimate reason to be flying below the minimum limits. For most private pilots, there is generally no reason to fly at low levels, except during take-off and landing, conducting a forced or precautionary landing, or to avoid adverse weather conditions.

__________

- Visual Meteorological Conditions is an aviation flight category in which visual flight rules (VFR) flight is permitted—that is, conditions in which pilots have sufficient visibility to fly the aircraft maintaining visual separation from terrain and other aircraft.

- Night Visual Flight Rules (NVFR) permit flight at night under the Visual Flight Rules (VFR) using visual navigation augmented by the use of radio navigation aids. Flight under the VFR (by day or night) must be conducted in Visual Meteorological Conditions (VMC), that specify minimum inflight visibility and vertical and horizontal distance from cloud.

- Last light is the time when the centre of the sun is at an angle of 6° below the horizon following sunset. At this time large objects are not definable but may be seen and the brightest stars are visible under clear atmospheric conditions. Last light can also be referred to as the end of evening civil twilight.

- Astronomical information calculated through www.ga.gov.au. The sun had an azimuth of 293° (north north-west) and an elevation of 3° below the level of the horizon.

The accident

While flying at low-level, the aircraft struck powerlines and lost control, resulting in the impact with terrain. The ATSB determined that the aircraft was capable of normal operation up until the wire strike. Upon striking the wires, the left wing aileron cable was severed, rendering the aircraft uncontrollable for the pilot. The aircraft subsequently rolled left and impact terrain at high speed. There was no pre-existing engine or airframe defects that would have contributed to the accident.

The witness descriptions and flight path of the aircraft indicated that the pilot had deliberately intended to overfly the Farmers Inn hotel. The considerable distance at which the aircraft travelled following the wire strike, as well as its configuration as found at the accident site, was not consistent with the pilot attempting to make an emergency landing. No operational reason could be identified for the pilot to fly at a height less than the minimum prescribed levels.

Analysis of the recorded GPS data indicated that the pilot had regularly flown at, and conducted hazardous low-level flying manoeuvres in the months preceding the accident. The pilot resided just outside the Burrumbuttock township and made regular flights over the town. It was therefore probable that he was aware of the presence and location of the powerline and the hazard that it posed. Powerline poles often provide good visual cues to enable a pilot to see the electrical wires. However, when the span between the poles is large this important visual cue is diminished or unavailable.

Additionally, at the time of the accident, the sun had set below the level of the horizon and the sky was overcast, thereby further reducing the ambient light. Under these conditions the pilot’s ability to detect the electrical wires was likely to have been significantly diminished.

Identifying the powerlines

Identifying powerlines and other similar obstructions from an aircraft in low-level flight is not a simple task. If the powerlines are in an area that is known to be a hazard for aircraft operations then they are required to be marked to enhance visibility. In this case, the powerlines were not required to be marked and, therefore, there was no enhancement to indicate their presence or assist in locating them. Factors such as windscreen visibility and environmental conditions can compound the problem of detection.

Wire strike accident investigations have often revealed that the pilot was aware of the presence and location of a powerline, but have nevertheless flown into it. The investigations have shown that even in the event that a subject pilot is able to detect the wires immediately prior to contact, the operating speed of the aircraft would severely limit the opportunity to react.

The effects of a wirestrike at low level are obvious; significant damage to the aircraft, usually leading to a loss of control and, because of the lower margin for recovery, subsequent impact with the ground or water. Pilots must keep in mind that not only do powerlines exist at low levels and in remote areas, they are also not easy to identify. Even against a clear blue sky, wires are difficult to spot for a number of reasons. Wires can oxidise to a blue/grey tinge and may blend into the background, or the wire may be obscured by terrain. Wires are very difficult to detect from the air and can be encountered in the most unexpected places in rural areas. Even if a pilot has spotted a powerline, the ability to judge its distance from the aircraft can be distorted by optical illusions or a lack of nearby visual reference points.

Low-level flying also presents fewer opportunities to recover from a loss of control compared to flight at higher altitudes. It takes time to react and to regain control of an aircraft should something go wrong.

Incapacitation

The postmortem medical examination revealed a pre-existing medical condition that could have led to the pilot being incapacitated during the flight in the moments leading up to the accident. Some coronary damage in the form of plaque haemorrhage and fibrin deposition to the pilot’s heart was found during the examination. Those changes are typically seen as an immediate precursor to a coronary artery thrombosis with the potential for a ‘heart attack’ and subsequent incapacitation. It was also possible that the arterial damage observed during the post-mortem examination had been induced by the impact forces experienced by the pilot.

While this pathological evidence cannot be discounted, the possibility of an incapacitating event is tempered by the facts surrounding the accident. The recorded data supports the numerous witness statements that the aircraft was being flown in a controlled manner and had been conducting low-level manoeuvring prior to the accident. Such operation of the aircraft was consistent with both witness accounts regarding previous flights and the recorded data from the GPS from previous flights.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to accident involving a Cessna 182L aircraft, registered VH-TRS, while being flown around Burrumbuttock, New South Wales on 20 July 2014. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Contributing factors

- While the pilot was operating at low level, the aircraft contacted electrical powerlines and collided with terrain.

Other factors that increased risk

- The pilot did not hold any approval to conduct low flying and had not received training in the identification of hazards or in the operating techniques for flight close to the ground.

Other findings

- There was no evidence of any defect with the aircraft that might have contributed to the accident.

- While it is possible that the pilot may have had a medical incapacitation event immediately prior to the accident, the aircraft was being operated in a manner consistent with previous flights undertaken by the pilot and at a level that provided little margin for error should such an event have been experienced.

- The powerline was not fitted with visual warning markers, nor was there a requirement for such markers in accordance with the Australian Standard.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2015

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |