What happened

At about 0525 Western Standard Time on 11 February 2015, the pilot of a Robinson R22 helicopter, registered VH-APP, departed from a camp site north of Kalbarri, Western Australia, with a passenger on board. The purpose of the flight was to conduct a reconnaissance of the area where goats were to be mustered that day. The role of the passenger was to point out landmarks relevant to the mustering operation. There was some confusion about the landmarks, but the pilot and passenger completed their reconnaissance then landed at another site (the goat yards) where the passenger disembarked.

From the goat yards, the pilot was to return to the muster area to commence the mustering operation. The passenger was himself also involved in the mustering operation, and had a ground vehicle pre-positioned at the goat yards.

When they landed at the goat yards, the passenger disembarked the helicopter under the supervision of the pilot, but the pilot still had some important points that he needed to clarify with the passenger. Rather than shut down the engine, the pilot elected to leave the helicopter running. After applying cyclic and collective control friction,[1] he disembarked the helicopter to follow the passenger. Having caught up with the passenger about 30 m from the running helicopter, they then engaged in a conversation to clarify the points of concern to the pilot.

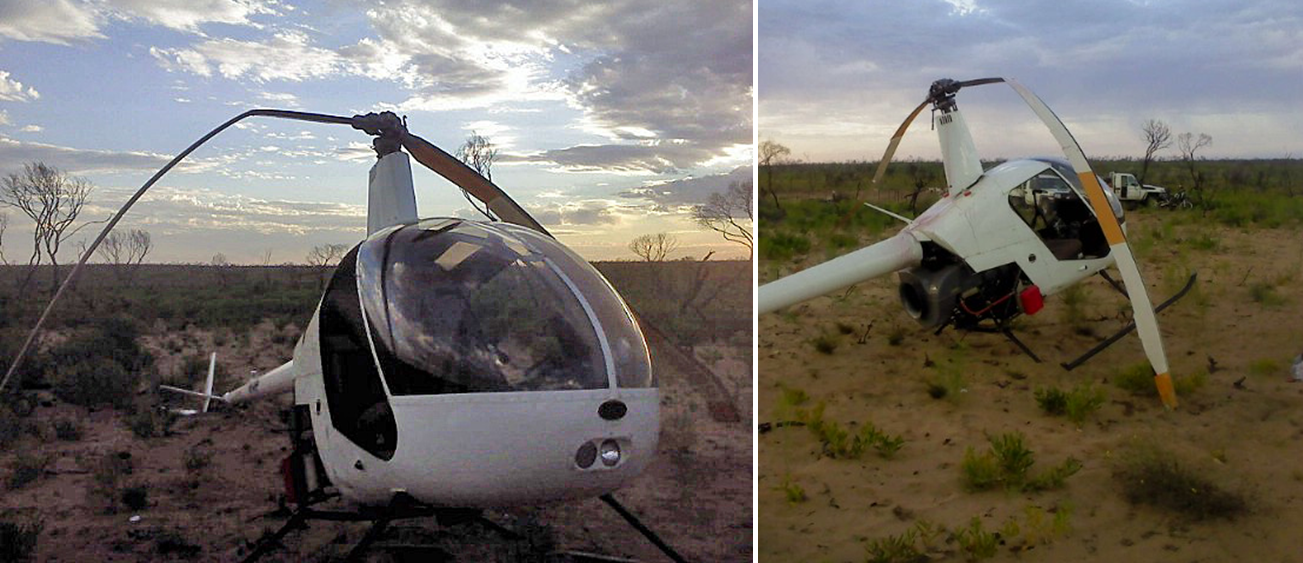

The pilot was unable to recall the exact length of time, but sometime in excess of about 2 minutes later, just as the pilot and passenger had concluded their conversation, the pilot heard the helicopter engine RPM increase and almost simultaneously, noticed that the helicopter was lifting clear of the ground. The helicopter climbed to a height of about 3 to 4 m above the ground and yawed through about 80 degrees to the left. The helicopter travelled backwards for a distance of about 8 m, remaining laterally level, and sank back to the ground with a significantly nose-high attitude. The tail of the helicopter struck the ground first, followed by the rear end of the skids. The tail rotor blades separated from the helicopter as the tail struck the ground and the rear part of the left skid broke away during the impact. The helicopter settled upright but during the accident sequence, the main rotor blades struck the ground and stopped abruptly. When the pilot was satisfied that it was safe to approach the helicopter, he moved forward and shut the engine down. Although the helicopter remained upright, it was substantially damaged (Figure 1). The pilot and passenger were both uninjured.

Figure 1: Helicopter damage

Source: Pilot

Pilot comments

The pilot believed that despite the application of control frictions, the vibration of the helicopter over the following couple of minutes (as he was engaged in conversation with the passenger) was enough to allow the collective to vibrate up with a commensurate application of engine power. He also commented that he was surprised at how quickly the accident happened. From the moment he heard the engine RPM begin to increase to the collision with terrain, was only a few seconds.

The pilot noted that he was possibly distracted at the time of the accident. Although he was an experienced mustering pilot, he had not mustered goats for some time. He was anxious to commence mustering as soon as possible that morning, mindful that in hot conditions goats were often more difficult to muster than cattle. Added to the distraction of perceived time pressure, the pilot had limited sleep during the evening prior to the accident and was generally mindful that it was likely to be a challenging day ahead. The pilot considered that with the benefit of hindsight, these distractions may have combined to influence his judgement in managing the circumstances surrounding the accident.

Robinson R22 Pilot’s Operating Handbook

The Normal Procedures in the R22 Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH) includes the caution: ‘Never leave helicopter flight controls unattended while engine is running.’[2] The POH also includes a number of important safety tips and notices. One Safety Notice with relevance to this accident is Safety Notice 17, which includes the following text:

NEVER EXIT HELICOPTER WITH ENGINE RUNNING

Several accidents have occurred when pilots momentarily left their helicopters unattended with the engine running and rotors turning. The collective can creep up, increasing both pitch and throttle, allowing the helicopter to lift off or roll out of control.

Along with a range of important reference information about Robinson Helicopters, the R22 POH is available on the Robinson Helicopter Company website under the Publications tab.

Company Operations Manual

The company Operations Manual permitted pilots to leave a company helicopter unattended with the engine running for a period not exceeding 5 minutes, under specific conditions. Those conditions related primarily to the operational circumstances and the operating environment. The conditions also required the pilot to lock the controls and ensure that passengers and any other personnel in the vicinity of the helicopter were appropriately managed. The pilot believed that he was operating in accordance with those conditions at the time of the accident.

Safety message

Leaving any vehicle unattended with the engine running carries considerable risk. Even where appropriate approvals are in place, pilots are encouraged to exercise extreme caution when considering the circumstances, and not allow perceived time pressures or other external factors to affect their judgement.

CASA Flight Safety Australia magazine Issue 91 (March/April 2013) includes an article titled Don’t Walk Away which discusses regulatory issues surrounding leaving a helicopter unattended with the engine running. Pilots and operators are encouraged to ensure that they are familiar with the relevant regulations and the conditions attached to any associated exemptions. Furthermore, operators are encouraged to seek advice from CASA where any doubt exists regarding application of the regulations or associated exemptions. The article also provides a summary of some accidents that resulted when pilots left helicopters unattended with the engine running. A copy of the March/April 2013 edition of the CASA Flight Safety Australia magazine is available on the CASA website.

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 42

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2015

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- The cyclic and collective are primary helicopter flight controls. The cyclic control is similar in some respects to an aircraft control column. Cyclic input tilts the main rotor disc varying the attitude of the helicopter and hence lateral direction. The collective control affects the pitch of the blades of the lifting rotor to control the vertical velocity of the helicopter. The collective control of the Robinson R22 incorporates a throttle mechanism designed to increase engine RPM automatically as collective is applied. Both the cyclic and collective controls are fitted with a friction mechanism.

- The POHs for Robinson Helicopter Company R44 series and R66 helicopters include the same caution.