Safety summary

What happened

On 23 October 2014, Genesee & Wyoming Australia (GWA) train 5DD2 departed from Kevin, a gypsum mine near Penong, South Australia. The train was loaded with gypsum destined for the port at Thevenard. Shortly after entering the Penong Junction to Thevenard section, the driver felt two severe jerks and noticed a loss of brake pipe pressure and an unusual amount of dust from the rear of the train. After the train was brought to a stop, the second driver walked back along the consist and found several derailed wagons and a section of damaged track.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the track infrastructure was generally in poor condition, with the rail exhibiting substantial head wear. The poor track condition had also allowed a wide gauge condition to develop, allowing rolling stock wheels to track away from the rail web. As a result of the head wear, gauge widening and the wheel tracking position, the capacity of the rail to support the wheel loads had been progressively reduced. This condition ultimately resulted in the failure of the rail head during the passage of train 5DD2, with the consequent derailment and infrastructure damage.

It was evident from the ATSB’s investigation that defect monitoring and reporting was not being conducted as specified in the relevant Code of Practice. As such, awareness of the rail condition and deterioration was reduced and remedial maintenance actions were not being planned or implemented.

The ATSB also found that Genesee & Wyoming Australia’s maintenance oversight had been limited, allowing the track to deteriorate to a point where trains could not be run safely.

What's been done as a result

Following the derailment, the track maintainer (Transfield Services) has undertaken to increase track inspection detail, with a view to identifying areas of concern for assessment and remedial works. GWA advised that they undertook their own inspection of identified sections of track with an emphasis on gauge and cant, and identified other locations that presented potential for a derailment to occur under similar circumstances. This resulted in the application of temporary speed restrictions over the affected areas and the insertion of timber sleepers to maintain gauge.

GWA also advised that they will undertake a review of the processes and procedures applied to rail infrastructure maintenance and have requested more regular track inspection reports from the contracted infrastructure maintainer. The ATSB has been advised that upgrade works are scheduled to improve the track condition and reduce the associated derailment risk, with the majority of works to be completed in 2015.

Safety message

This incident illustrates the importance of rail maintainers effectively documenting and accurately reporting the condition of the track to the responsible owner/operator. Similarly, owners and operators must maintain diligent oversight of infrastructure maintenance activity, particularly in areas where the track condition is known to be poor or deteriorating.

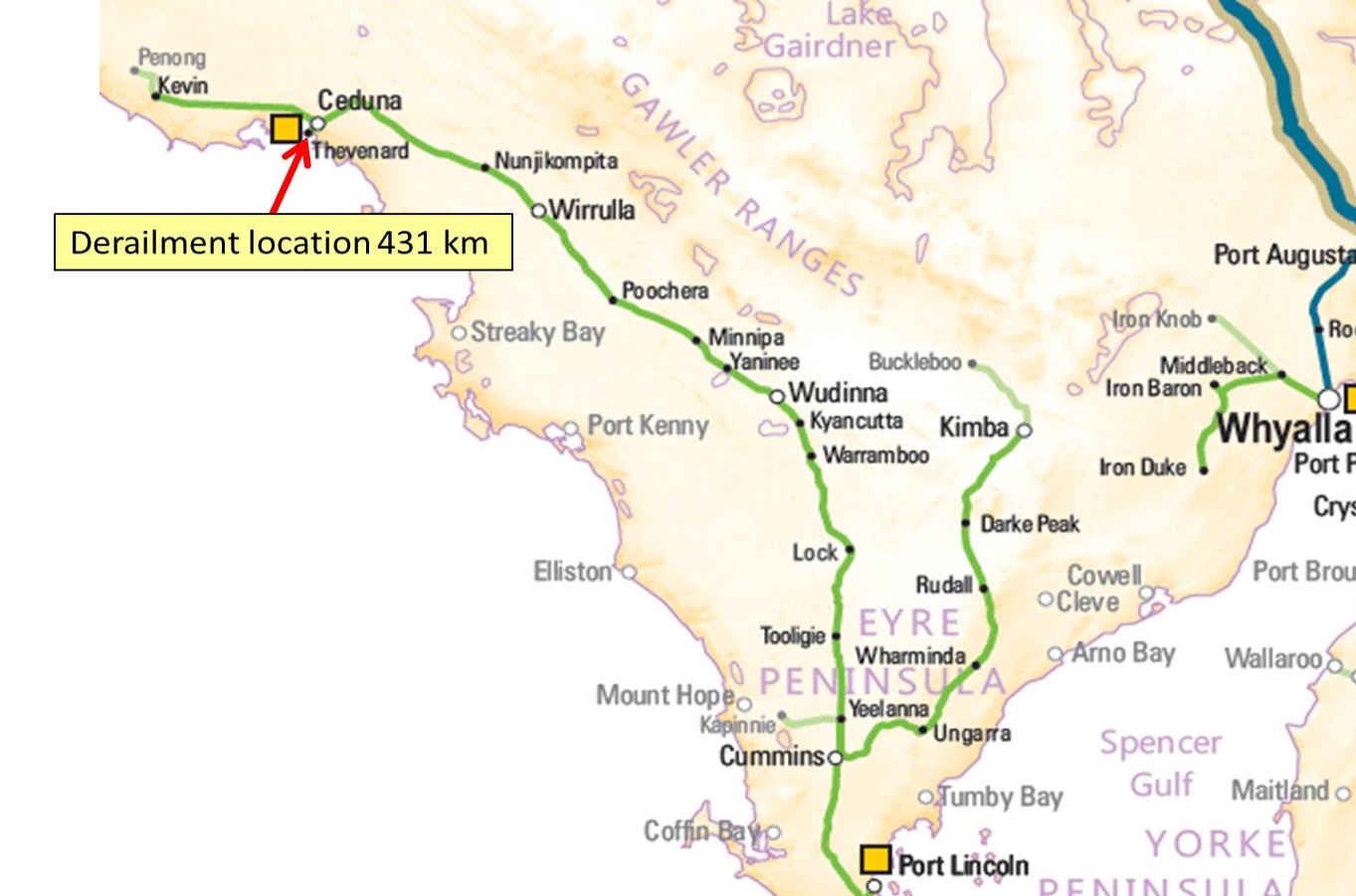

At about 0230[1] on 23 October 2014, the crew for Genesee & Wyoming Australia (GWA) train 5DD1 signed on for duty at Thevenard, South Australia. The train was scheduled to travel empty from Thevenard to the Gypsum Resources Australia mine at Kevin (Figure 1), to be loaded with gypsum before returning to Thevenard.

Figure 1: Derailment location map - South Australia

Source: NatMap Railways of Australia annotated by ATSB

At about 0300, the empty train departed Thevenard for the mine, arriving at 0507. After the completion of loading, the train departed the mine at 0636 as train 5DD2.

The Kevin to Thevenard track section had speed restrictions for loaded locomotives; varying from 20km/h to 30km/h due to poor track condition and geometry. As 5DD2 approached Thevenard, the driver increased the train speed to the permitted limit of 30km/h. At about 0906, the driver felt two severe jerks, followed shortly after by a loss of brake pipe air pressure, and then noted an unusual amount of dust rising from the rear of the train. The train was brought to a stop near the 431 km mark[2].

At 0908, the driver contacted train control to advise that the train may have derailed, while the second driver walked back along the train to assess the situation. At 0919 the crew confirmed their location with train control and advised that the rear 13 wagons had derailed.

As the train had derailed and stopped on the approach to the level crossing at Kloeden Street, it caused the level crossing equipment to ring continuously. Consequently, the police attended the site at about 0923.

There were no injuries caused by the derailment, but approximately 120 m of track and 13 wagons were damaged. The track was reinstated for use on 26 October 2014.

__________

Location

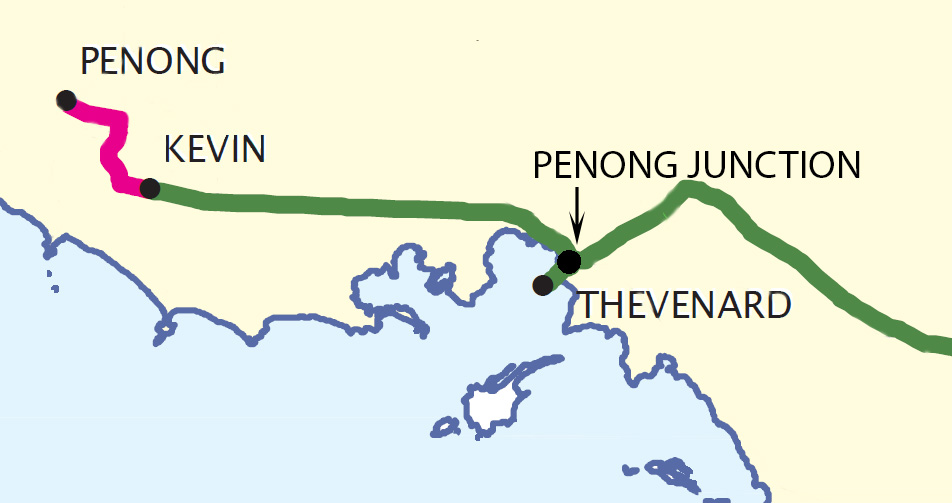

Thevenard is located on the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia, near Ceduna. The rail line extends from Kevin, where a gypsum mine is located, through to Thevenard where the port handles bulk gypsum shipments.

The derailment occurred at the 431.225 km point between Penong Junction and Thevenard (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Map of the Penong – Thevenard track system

Source: South Australian Government, Department for Transport, Energy and Infrastructure, annotated by ATSB

Train and crew information

Train 5DD2 was a gypsum transport service that operated between Kevin and Thevenard. The train consisted of three locomotives (GWA 1601 leading, GWA 873 and GWA 850 trailing) hauling 55 ore hopper wagons of type ENH and ENHA. The train had an overall length of 424 m and a gross weight of 2,475 tonnes. The locomotives were equipped with Quantum event recorders; the information from which was downloaded by GWA and provided to the ATSB for use in the investigation.

ATSB analysis of the information from the train’s recorders indicated that there had been no handling issues experienced during the lead up to the derailment.

As part of the post-derailment investigation, the involved wagons’ wheel profiles were checked by the operator and found to be within serviceable limits.

Train crew

The train was crewed by two drivers; both were appropriately qualified, held the required route certifications and were assessed as fit for duty.

Following the derailment, the drivers underwent mandatory testing for prior drug and alcohol use, with negative results returned for both.

Track Information

History

The Thevenard to Kevin track was a single, narrow gauge[3] railway line from the Port of Thevenard, through Ceduna to the Penong Junction and on to Kevin (Figure 2). The track consisted of a mixture of mechanically-jointed 63 lb/yd (31 kg/m) and 82 lb/yd (41 kg/m) rail, directly fastened to wooden sleepers. The track section where the derailment occurred was constructed in 1915, with the line from the Penong Junction to Kevin being laid in the 1960s. The line was originally operated by South Australian Railways until the mid-1970s, after which it was used by a number of operators. In 1997, a ground lease was granted to Australian Southern Railroad (now GWA). Information available to the ATSB indicated that the general condition of the line had been degrading significantly over a number of years; influenced primarily by limited infrastructure investment and maintenance activity.

The mine at Kevin had been owned and operated by Gypsum Resources Australia since 1984. Penong, located beyond Kevin, had grain storage and loading facilities, but this section of line was closed to rail traffic in 1997 due to minimal use and poor track condition. In a submission to Infrastructure Australia in 2008, the Eyre Regional Development Board identified that significant upgrading and capital investment was required to maintain the rail in an efficient operational state. The investment was not deemed economically justified, unless the gypsum mine could be guaranteed to have continued operations for a number of years.

In 2006, Transfield Services, under contract to GWA, became responsible for the ongoing maintenance and serviceability of the Thevenard to Kevin line. A capital upgrade program was initially proposed for 2013, but the works were further delayed as a commercial agreement with the mine (to ensure continued usage of the rail line) was not yet in place. In July 2014, an agreement was reached with the mine to justify the capital investment needed. A capital works program was then initiated, with a walk-through inspection identifying the scope of the project in August 2014, and capital works scheduled to begin in 2015.

Site observations

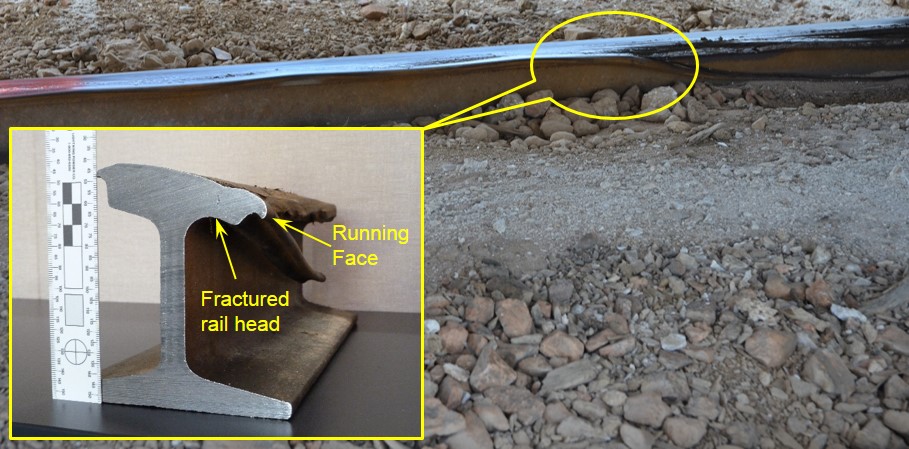

Examination of the rail in the area immediately prior to, and at the point of derailment (POD), indicated that the left hand side rail head (in the direction of travel) had fractured near the running face (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Fractured rail head

Source: ATSB and ONRSR

Source: ATSB and ONRSR

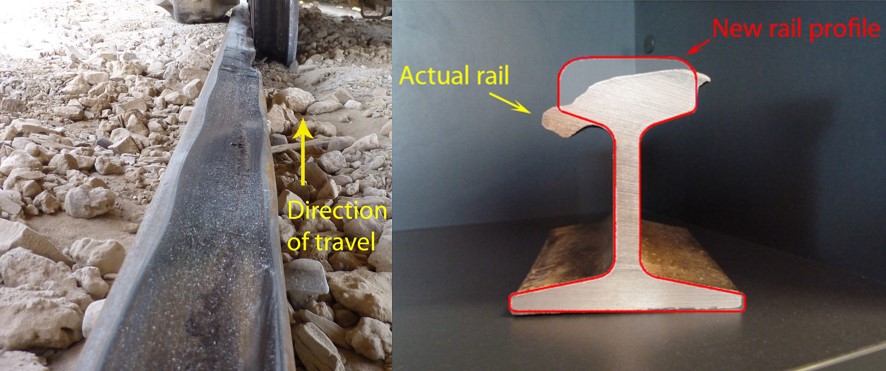

The track showed substantial rail head wear, with evidence of significant metal flow and corrugation (Figure 4). In addition, the wear pattern on the rail face indicated that wheel flanges had been tracking at least 20mm inboard from the rail running face, suggesting lateral (gauge-widening) movement of one or both rails through the POD.

Figure 4: Rail head wear, metal flow and corrugations

Source: ATSB and ONRSR

The combination of substantial head wear and the wheel tracking location increased the likelihood of rail head failure during the passage of a train. From the extent of wear and deformation of the rail head, the lateral movement of the track, and the inboard tracking position of the wheels, the ATSB concluded that the rail had been structurally unable to support the wheel loads, resulting in the vertical collapse and fracturing of the rail head during the passage of train 5DD2.

Given the extent of the rail head wear sustained, and that this type of damage develops progressively over time, it is very likely that the degradation would have been evident during any previous scheduled track inspections.

Inspection and maintenance

Track infrastructure deteriorates over time as a result of usage, age and other factors. It is the infrastructure manager’s role to implement a maintenance regime to ensure the track condition is periodically assessed and returned to an acceptable standard if defects are found. The process is based on a regime of inspection and maintenance aimed at ensuring that the infrastructure condition remains at or above defined limits that are appropriate for the operating requirements of the rail line. It is possible for trains to operate safely on infrastructure that is in a condition below defined limits, provided that appropriate measures are implemented to manage the associated risks.

In this case, the track inspection and maintenance standards were documented in the Westrail Narrow Gauge Mainline Code of Practice (CoP). The CoP specified the monitoring and maintenance requirements, including:

- the type of inspections and the frequency required

- the documentation requirements after track inspections

- acceptable wear limits, and

- maintenance requirements for detected defects.

- Considering the degraded condition of the Eyre Peninsula rail infrastructure, GWA had issued an addendum to the CoP (dated 1 April 2007), which provided for more frequent inspections, reduced maximum track speeds and modified maintenance defect limits.

Processes

In general, the track maintenance process required identification of track defects through routine inspection, followed by a planning phase to determine the work required and a Work Order being issued to conduct the remediation. To this end, Transfield Services maintained a track fault list; a consolidated list of defects detected during track inspections and the associated rectification work planned. Transfield used this consolidated list to schedule works, and it was the only documentation provided to GWA for their oversight of the state of the track.

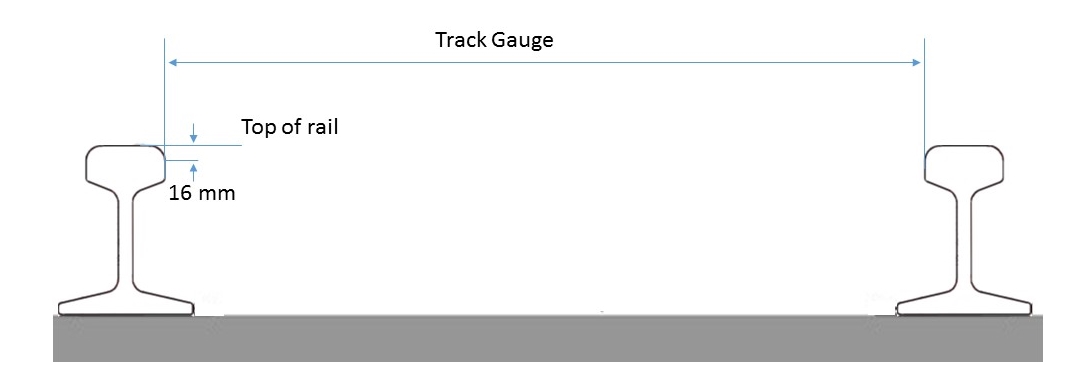

Track gauge

Track gauge is the distance between the gauge faces of the two rails and is normally measured at a point 16 mm below the top of the rail head (Figure 5). In this case, the rail head was so worn and distorted that track gauge could not be effectively measured in this manner during post-derailment inspections. Considering the evident running position of the rail wheels however, (Figure 6), the track gauge had very likely exceeded the maximum limit documented in the CoP addendum.

Figure 5: Track gauge measurement point

Figure 6: Rail condition and running position of wheels

The condition of sleepers and fasteners is critical for maintaining track gauge. In this case, their condition would have been difficult to determine visually, due to extensive coverage by gypsum product (Figure 7). Post-derailment examination however, found that the sleepers were in a poor condition, with limited gauge-holding capacity at the point of derailment. While the period over which gauge widening and poor sleeper/fastener condition had developed was unable to be determined, the level of rail wear and sleeper condition suggested that the track had been operating in a degraded condition for some time.

Rail condition

The CoP required rail head wear to be periodically assessed against prescribed limits, with defects beyond those limits reported for remedial action. Documentation is required detailing the location and wear levels where top or combined wear to the head profile exceeds 20% and side wear is greater than 15%. Where the prescribed wear limits are exceeded, a rating of the rail may be carried out using procedures detailed in the CoP, taking into account local factors and any pre-existing speed restrictions.

Corrugation of the rail was also evident at the point of derailment – a defect which develops over time and can lead to failure of the rail if left untreated. It was evident that this condition had been present for some time and would likely have been visible during scheduled track inspections.

During the investigation, the ATSB was unable to identify any documented evidence that the level of rail head wear or corrugation in the area of the derailment was being monitored, or that the severity of the condition/s had been reported to GWA for reassessment of operating limitations (load rating and speed restrictions).

Figure 7: Complete product coverage of sleepers and fasteners

Source: ATSB and ONRSR

Track inspection

The documentation suite in use for track inspection outlined the requirements for patrol, general and detailed inspections; all of which were used in conjunction with Transfield’s Technical Maintenance Plan to meet the CoP requirements. These documents detailed the procedures for completing the different types of inspections on various rail infrastructure elements, and contained inspection worksheets to record details of completed inspections and corrective work performed.

At the time of the derailment, the minimum (baseline) inspection requirements prescribed by the CoP addendum were for a scheduled track patrol to be conducted every 48 hours, a track geometry car to be run at a minimum of once a year, and on-rail ultrasonic testing required every 8 years.

While the CoP addendum procedures required 48-hourly inspections, there were no records available to confirm that those inspections had taken place between June 2014 and the derailment in October. Records were also unable to establish when the last track geometry car was run to detect and quantify any rail head defects. The track geometry car had the capability of detecting wide track gauge as well as the extent of the rail head wear.

Records provided to the investigation showed that the most recent ultrasonic testing was conducted in 2006, with no defects noted at the point of derailment at that time. The next ultrasonic test was due in 2014, however an earlier decision had been made, in light of the upgrade work proposed in 2013, to run that test during the early stages of the upgrade program.

Track maintenance

The risks presented by the deteriorating track infrastructure were able to be managed in accordance with the CoP and addendum, by applying operational restrictions and increasing the inspection frequency. The temporary speed restrictions in force at the point of derailment were applied in 2009, when Transfield Services was first contracted to provide track maintenance services.

The CoP indicated that speed restrictions, when used in conjunction with increased inspection frequency, were an appropriate risk control for some isolated defects until such time as the defects were rectified or a plan for a strategic upgrade was in place. While temporary speed restrictions can reduce the likelihood and consequences of an incident involving degraded track, they were not intended to be used as long term measures for ensuring the safety of the line.

At the time of the occurrence, other sections of the Eyre Peninsula rail infrastructure had been either closed due to the condition of the track, or had current speed restrictions, with the maximum line speed for a loaded train of 30 km/h. All of the speed restrictions current at the time of the derailment had been applied as a response to the state of the infrastructure.

Related occurrence

Derailment at Charra, November 2 2014

At about 1800 hours on 2 November 2014, train 1DD5 derailed at the 473.938 km mark between Kevin and the Penong junction. Subsequent investigation found a 200 mm section of broken rail associated with a mechanical joint. It was concluded that the broken section had separated during the passage of 1DD5 (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Rail defect in mechanical joint

Source: Transfield Services

While records of the inspections conducted after June 2014 were unavailable, the evidence of forced surface contact across the fractured web suggested the fracture within the mechanical joint had likely been present for a period longer than the time between inspections.

Investigations at the time found no records of routine inspections taking place at a frequency that would have detected the broken rail prior to the passage of the train. Similarly, there were no indications that a potential issue was being monitored and maintained appropriately, or had been reported to the rail operator.

__________

On the basis of the evidence available from the incident site, it was concluded that the derailment of train 5DD2 resulted from the combined effects of a substantially worn rail head profile and wide track gauge. These conditions are characteristic of aging and deteriorating infrastructure. To properly manage a deteriorating asset, GWA, as the rail transport operator (RTO), was responsible for ensuring the standards being applied were appropriate for safe rail operations. This required an appropriate level of oversight of the contracted maintenance provider. As that provider, Transfield Services was required to periodically inspect, record and report the condition of the track to GWA, so that appropriate assessments and decisions could be made in managing the track condition.

Documentation and reporting

The ATSB found no evidence to indicate that regular (visual) defect monitoring and reporting was being conducted as specified in the CoP. As a result, remedial maintenance actions were not being planned or implemented. Records of routine inspections were not being kept, and accordingly, there was no information indicating the condition of the rail at the point of derailment. Without defects being recorded and entered into the maintenance scheduling system, no monitoring or maintenance actions were being implemented. Similarly, without the appropriate documentation and reporting, it was likely that GWA was not fully aware of the deteriorated state of the rail and the potential requirement for immediate maintenance actions.

In a similar manner, it was also evident that the track geometry inspection car was not being run at the required intervals. Use of the track geometry car may have identified any track alignment, wide gauge or rail head wear defects that required immediate action and which may not have been noted by visual (hi-rail) running inspections.

The track fault list examined by the ATSB did not include monitored defects, and had no entries between June 2014 and the incident – suggesting that known defects were not being monitored and new defects were not being identified and added to the list.

There was physical evidence to suggest that the defects which contributed to the derailment had been present for a significant period of time – further indicating that the inspection regime was not capturing defects or monitoring them appropriately. The nature of the track defects present at the derailment site (substantial rail head wear, wide gauge and corrugation) was such that they should have been identifiable during routine inspections, and consequently, should have been subject to a monitoring regime as defined within the CoP.

Oversight

The application of temporary speed restrictions in 2009, coupled with an increase in the inspection frequency of the track at the point of derailment suggested that from this time, there was at least a broad level of understanding around the deteriorated state of the track. The CoP indicated that speed restrictions and increased inspection frequency was an acceptable minimum response when applied to isolated defects, however it also indicated that a more comprehensive response may be necessary where multiple defects exist in a localised area. GWA had identified that a major upgrade was required to address the cumulative risks, but the implementation of this had been delayed due to ongoing commercial negotiations with the mine operator.

Whilst Transfield cited track occupancy authorities and daily work diaries as evidence that track inspections had occurred, there were no specific inspection records, nor were there any reports of defects found or maintenance action taken following these regular inspections. GWA had not required the routine provision of inspection records, with the only documentation received for oversight of the track condition being a consolidated track fault list provided quarterly. The track fault list contained no defects found or rectification work conducted as a result of routine inspections between June 2014 and the incident. The level of detail contained in the fault list was not sufficient to fully convey the deteriorated state of the track, and defects that required on-going monitoring were not included in the list. As such, GWA was likely not fully aware of the true state of the track infrastructure.

Where the rail was known to be in poor condition, GWA had not maintained sufficient oversight in managing the activities of the infrastructure maintainer. The limited information requested from, or provided by the contracted maintenance provider resulted in GWA being unable to effectively manage the deteriorating condition of the track. This led to the track remaining in operation while it deteriorated to a level below the limits documented in the CoP and addendum, and without having undergone a process of standards reassessment to ensure that ongoing rail operations remained safe.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the derailment of train 5DD2 at Ceduna, South Australia, on 23 October 2014. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Safety issues, or system problems, are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is an event or condition that increases safety risk and (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time.

Contributing factors

- The track infrastructure between Penong and Thevenard, SA had progressively degraded and was generally in poor condition.

- Substantial rail head wear and corrugation in the vicinity of the derailment, combined with a wide gauge condition and the consequent wheel tracking away from the rail web led to localised rail head failure and the derailment of train 5DD2.

- Track defect monitoring and reporting was not being conducted as specified in theWestrail Narrow Gauge Mainline Code of Practice, limiting the awareness of the deteriorating track condition and the need for reassessment of track operating limits. [Safety issue]

- The rail transport operator (GWA) had not maintained sufficient oversight of the activities of the rail infrastructure manager (Transfield Services), allowing the track to deteriorate to a level where trains could not be reliably run in a safe manner. [Safety Issue]

The safety issues identified during this investigation are listed in the Findings and Safety issues and actions sections of this report. The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) expects that all safety issues identified by the investigation should be addressed by the relevant organisation(s). In addressing those issues, the ATSB prefers to encourage relevant organisation(s) to proactively initiate safety action, rather than to issue formal safety recommendations or safety advisory notices.

All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation.

Where relevant, safety issues and actions will be updated on the ATSB website as information comes to hand. The initial public version of these safety issues and actions are in PDF on the ATSB website.

Maintenance, defect monitoring and reporting as per CoP

Track defect monitoring and reporting was not being conducted as specified in the Westrail Narrow Gauge Mainline Code of Practice, limiting the awareness of the deteriorating track condition and the need for reassessment of track operating limits.

Safety Issue number: RO-2014-018-SI-01

Oversight of Infrastructure Maintenance

The rail transport operator (GWA) had not maintained sufficient oversight of the activities of the rail infrastructure manager (Transfield Services), allowing the track to deteriorate to a level where trains could not be reliably run in a safe manner.

Safety Issue number: RO-2014-018-SI-02

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- Genesee & Wyoming Australia

- Transfield Services Ltd

- Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator

References

- Rail Industry Safety and Standards Board (2010), Glossary of Rail Terminology – Guideline. Available from: www.rissb.com.au

- AS 1085.1 - Railway track material—Steel rails—History (Supplement 1 to AS 1085.1—2002).

- Westrail Narrow Gauge Mainline Code of Practice Version Draft 1998

- Addendum to the Westnet Rail Narrow Gauge Mainline Code of Practice for the Eyre Peninsula Railroad

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to Genesee & Wyoming Australia, Transfield Services, the Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator (ONRSR) and the crew of train 5DD2.

Submissions were received from Genesee & Wyoming Australia and the Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator (ONRSR). The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2015

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |