Contact with the wharf by Big Glory

A limited-scope, fact-gathering investigation into this occurrence was conducted in order to produce this short summary report and allow for greater industry awareness of potential safety issues and possible safety actions.

What happened

At 0706[1] on 20 November 2014, two port pilots boarded Big Glory (cover) off Cape Flattery (Figure 1), where the ship was to berth for loading silica sand.[2] The pilot assigned to the pilotage task was very experienced and had performed about 70 pilotages into the port, including about 15 on Big Glory. As he was returning after 6 months leave, procedures required that he undergo a check pilotage.

Figure 1: Cape Flattery

Source: ATSB

Figure 2: Big Glory’s planned and actual positions

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland with ATSB annotations

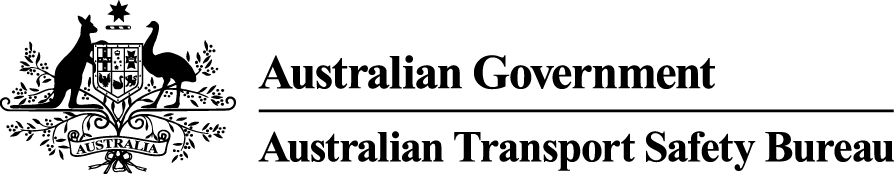

Once on the ship’s navigation bridge, the pilot exchanged information with the master and discussed the pilotage plan (Figure 2). The pilot advised that the current in the area was flowing northeast[3] at 0.2 knots[4] and high tide was at 0755. The wind at the time was from the southeast at 15 knots. The master confirmed that all the ship’s equipment, including the main engine, was in order. The officer of the watch and the seaman steering the ship were the other members of the bridge team.

At 0715, the pilot took over the conduct of Big Glory with the check pilot observing. He manoeuvred the ship onto the line of the approach leads using visual cues and the ship’s radar while progressively reducing its speed.

By 0740, the ship was positioned along the line of the approach leads about five ship lengths (about 1 km) from the wharf (Figure 2). Its speed was about 3.4 knots and decreasing with the main engine stopped. The pilot established radio contact with the loading supervisor on the wharf and asked him to report as the ship’s bow passed each breasting dolphin (BD) there. [5]

At 0744½, the ship’s speed had decreased to about 2.6 knots and the main engine was run dead slow ahead. Two work boats also arrived near the ship to assist, mainly to assist running mooring ropes when berthing. The port has no tugs and the workboats have limited tug ability.[6]

By 0746½, Big Glory’s speed had increased to about 3.5 knots. The main engine was stopped and then run dead slow astern. The pilot felt that the ship’s speed was not decreasing as expected and he was concerned the ship would overshoot the planned anchor let go position. Hence, main engine power was progressively increased, including about 30 seconds at full astern.

At 0749, the main engine was stopped and the ship was no longer moving ahead. At about this time, the wharf supervisor reported to the pilot that the bow was in line with BD1 (Figure 2). The pilot asked the master to have the crew standby to let go the port anchor.

At this stage, the pilot observed Big Glory being ‘rapidly set on to the wharf’ and considered aborting the berthing. He decided against aborting because he was certain that the ship’s ‘stern would make substantial contact with the wharf’.

A few seconds after 0749, the main engine was run ahead in an attempt to gain headway and manoeuvre Big Glory to the planned anchor let go position some 150 m ahead. The engine was run ahead at up to half power until shortly before 0751, when it was stopped. The ship’s bow was now about 60 m from the wharf and about 100 m away from the planned anchor let go position.

At 0751, the pilot asked for the port anchor to be let go and held on to with two shackles[7] on deck. The main engine was ordered astern and power progressively increased to full astern before it was stopped shortly after 0752. The ship’s headway reduced as it moved towards the wharf.

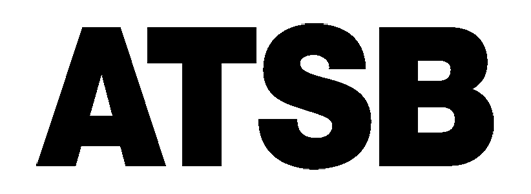

At about 0754, Big Glory made contact with the dolphin (Figures 2 and 4). The ship’s hull, at the aft end of number one cargo hold, was damaged about 1.5 m above the ballast water line. The shell plating was set-in in two locations about 1 m apart (Figure 3). Part of a steel bracket on the dolphin penetrated the plating leaving a hole about 180 mm x 60 mm. The bracket was partially torn off and the deck plating on the dolphin was dislodged (Figure 4).

|

Figure 3: Damage to the ship’s hull

|

Figure 4: Damage to the dolphin

|

Shortly afterwards, the wharf supervisor asked the pilot to move the ship clear of the wharf to allow an inspection of the damage to the dolphin. At 0756, the pilot began manoeuvring the ship off the wharf using the workboat forward to push on the starboard bow while heaving the anchor.

At 0810, Big Glory was clear of the wharf. The pilot handed over conduct of the ship to the check pilot and the ship was moved to a safe location within port limits.

At 1306, after some minor repairs to the dolphin were complete, the check pilot started manoeuvring the ship back to the berth. By 1420, the ship was all fast alongside the wharf.

On 25 November, temporary repairs to Big Glory’s hull to allow it to sail on the next voyage were completed. Subsequently, the ship loaded its cargo.

Maritime Safety Queensland investigation

Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ), the regulatory agency responsible for pilotage at Cape Flattery, conducted an internal investigation into the incident that concluded that the pilot’s loss of situational awareness and error of judgment were the main contributing factors to the incident.

ATSB comment

As Big Glory approached the planned anchor let go position, astern propulsion was used for 90 seconds because the pilot felt that the ship’s speed was not decreasing. However, its speed was decreasing, and the ship stopped 150 m short of the anchor let go position. Ahead propulsion was then used for 90 seconds before the port anchor was let go in a position much closer to the wharf than planned (60 m instead of 150-160 m). The particular combination of the ships’ main engine and rudder movements in the prevailing wind and current resulted in a lateral movement (to starboard) towards the wharf. The use of two shackles of anchor cable as planned suggests that adjusting anchor/cable use to recover from the uncontrolled situation was not considered. Subsequently, the ship’s hull contacted the mooring dolphin with sufficient force to damage its shell plating and the dolphin. The pilot’s perception of the ship’s movement during the critical stages of the approach to the wharf is indicative of his situational awareness at the time.

Safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence.

Maritime Safety Queensland

As a result of its investigation, MSQ’s safety action included the following recommendations:

Pilotage procedures

- A review of the Cape Flattery pilotage plan to include an ‘abort’ position and a more accurate track to the ‘anchor position’.

- Portable pilotage unit (PPU) usage to be made compulsory for all Cape Flattery berthings.

- A requirement for pilots returning from leave exceeding 4 months to complete at least three mentored trips (inward) before undergoing a check pilotage.

Safety message

Bridge resource management (BRM) is critical to safely managing risks in a pilotage. Key elements of BRM include proper planning, execution and monitoring using all available resources. The use of electronic aids to navigation to support traditional methods of pilotage and navigation can significantly enhance the position monitoring ability and situational awareness of the bridge team and, thus, reduce the risk of an incident.

The ATSB SafetyWatch initiative highlights the broad safety concerns that come out of our investigation findings and from the occurrence data reported to us by industry. Maritime pilotage is one of the safety concerns, with further information available from the ATSB’s website.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2015

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] All times referred to in this report are local time, Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 10 hours. Wherever possible, these times are as recorded by Big Glory’s voyage data recorder (VDR).

[2] Cape Flattery is the world’s largest silica sand export port currently exporting about 1.7 million tonnes per year.

[3] The current was actually flowing southwest (the graph provided to the pilots by the port before they boarded indicated that the direction and speed of the current at 0530 that day was 225º at 0.15 knots).

[4] One knot, or one nautical mile per hour, equals 1.852 kilometres per hour.

[5] A dolphin is a structure separate to the wharf, against which a ship can lie or its mooring lines can be run to.

[6] The bollard pull of the workboats attending the ship forward and aft was 17 t and 12 t, respectively.

[7] One shackle equals 90 feet or 27.43 m.

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland Source: Maritime Safety Queensland

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland