Preliminary report released 10 October 2013

This preliminary report details factual information established in the investigation’s early evidence collection phase and has been prepared to provide timely information to the industry and public. Preliminary reports contain no analysis or findings, which will be detailed in the investigation’s final report. The information contained in this preliminary report is released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003.

The occurrence

On 20 September 2013, a loss of separation1 occurred between an Airbus A330 aircraft, registered VH-EBO (EBO) operating a scheduled passenger service from Sydney, New South Wales to Perth, Western Australia, and an Airbus A330 aircraft, registered VH‑EBS (EBS), operating a scheduled passenger service from Perth to Sydney. Both aircraft were within radar surveillance coverage at the time of the occurrence.

At 1159:56 Eastern Standard Time2, following a handover/takeover, an air traffic controller in Airservices Australia’s Melbourne Centre accepted control jurisdiction for the Augusta and Spencer airspace sectors (Figure 1), which were permanently operated in a combined configuration. The Augusta/Spencer controller had previously been monitoring another controller who was conducting a familiarisation shift, following a period of leave, on the air traffic control (ATC) group’s other two sectors (Tailem Bend and Kingscote), which were also permanently combined. The Augusta/Spencer controller was preparing to also take over the Tailem Bend/Kingscote sectors on the same one console, as sector traffic levels and controller workloads were relatively low.

It was normal practice for all of the group’s sectors to be combined at that time of day due to low traffic levels.

Figure 1: Augusta/Spencer and Tailem Bend/Kingscote airspace sectors

Source: Airservices Australia. Image modified by the ATSB.

At the time the controller assumed control of the Augusta and Spencer sectors, EBS was within the Augusta/Spencer airspace at a position 140 NM (259 km) west of Adelaide, South Australia, eastbound on the one-way route Y135 at flight level (FL)3 390. EBO was within the adjoining eastern airspace (Tailem Bend/Kingscote), 79.6 NM (147 km) to the east of Adelaide and westbound at FL 380.

At 1210:15, EBO’s flight crew contacted the Augusta/Spencer controller as the aircraft approached the airspace boundary. The controller observed that the ATC computer system’s human machine interface prompts displayed on their screen provided a conflicting indication as to whether onwards coordination with the adjoining western sector (Forrest) controller had been completed. To assure that this coordination had been carried out, the Augusta/Spencer controller called the Forrest controller via the internal coordination line at 1211:34 and was advised that coordination had already been completed. In addition, the Forrest controller advised that they had no vertical restrictions for EBO. The Augusta/Spencer controller entered that information into the operational data line of the aircraft’s label in the ATC computer system, and then completed other tasks in preparation for assuming control of the Tailem Bend/Kingscote sectors.

At 1212:57, EBO’s flight crew requested climb from FL 380 to FL 400, which the controller immediately approved. This resulted in a loss of separation assurance4 between EBO and EBS as the vertical separation standard of 1,000 ft would not exist when the aircraft passed on their one-way routes at a point where there would be less than the required radar separation standard distance laterally of 5 NM (9.3 km).

At the time the climb request was approved, EBO was west of Adelaide and tracking in a westerly direction on the one-way air route designed Q12 (Figure 1). EBS was west of Adelaide, tracking in an easterly direction on one-way route Y135. On receipt of the level change clearance, EBO’s flight crew reported leaving FL 380 and recorded data from the aircraft showed that it commenced climbing at 1213:08.

At about 1213:32, before both the radar and vertical separation standards were infringed, the ATC system’s Short Term Conflict Alert (STCA) activated, alerting the controller to the imminent loss of separation between EBO and EBS. The controller immediately instructed EBO’s flight crew to maintain FL 380, which the crew acknowledged with advice that they were descending back to that level. Recorded data from EBO showed that the aircraft reached a maximum altitude of 38,350 ft at 1213:37.

Recorded data from EBS showed that, at 1213:27, the crew received a traffic advisory (TA)5 from their aircraft’s traffic collision avoidance system (TCAS)6 At 1213:37 the TA changed to a resolution advisory (RA),7 and at 1213:44 the EBS flight crew advised the controller that they were responding to an RA and the aircraft started to climb.

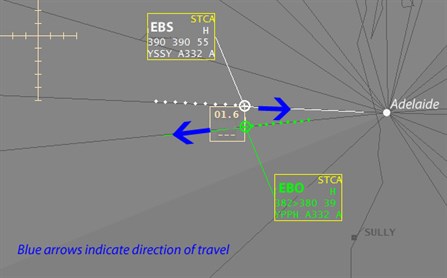

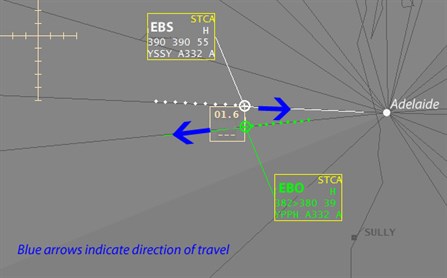

Recorded data from the two aircraft showed that the minimum vertical separation was 650 ft at 1213:37, when the two aircraft were 4.1 NM (8 km) apart laterally. The minimum lateral separation was 1.6 NM (3 km) at 1213:51, when the aircraft were 870 ft apart vertically (Figure 2). At that time both the vertical and lateral separation were increasing as the aircraft were on separate one-way routes. The vertical and radar separation standards were re-established a short time later.

Figure 2: Aircraft positions at 1213:53

Source: Airservices Australia. Image modified by the ATSB.

Note: Data in this figure is provided from the ATC system with a different level of resolution compared to the data provided from the aircraft’s recorders. The figures ‘55’ and ‘39’ refer to the ground speeds of the aircraft (divided by 10).

Air traffic control information

The Augusta/Spencer controller was initially rated as a controller in 2005. Prior to 20 September 2013, they had the previous 3 days off duty. They reported receiving a normal amount of sleep in the previous two nights, and they commenced their shift on 20 September at 0700.

Controllers reported that workload was relatively low at the time of the occurrence and that there were no operational distractions.

TCAS information

The flight crew of EBS reported that, at the time that the EBO flight crew requested clearance to climb to FL 400, they had acquired EBO visually and observed it on their TCAS display. They could see EBO was heading in the opposite direction and that it appeared to be on a diverging route. They also saw EBO climbing and diverging to the south on the TCAS display before receiving the TA and the RA.

Immediately following the occurrence, EBO’s flight crew advised the Augusta/Spencer controller that they did not receive any indications on their TCAS display of the presence of EBS. The flight crew later reported that they did not see EBS on their TCAS display, and they did not receive a TA or RA. They also reported not being able to see other aircraft on their TCAS display during the rest of their flight in situations where the other aircraft’s crews could see them, until reaching the Perth Terminal Area, where traffic returns were evident. They had been able to see other aircraft on departure from Sydney and there was no indication of a TCAS failure prior to the loss of separation event.

Examination of recorded data from EBO showed that no TA or RA was received. After the aircraft landed in Perth, a built-in test equipment (BITE) test was conducted on the TCAS with no faults indicated. A minimum equipment list (MEL)8 was applied for the unserviceable TCAS for the return flight to Sydney. A full system test was conducted in Sydney with a failure identified between ATC transponder 2 and the TCAS computer and TCAS antennas. The TCAS computer and ATC transponder 2 were replaced with spare units and a further system test carried out with nil faults detected.

Although all air transport aircraft are required to have a TCAS, on rare occasions the system can fail or lose functionality during a flight. In such situations a flight crew is usually provided with a fault message, and the flight crew are required to advise ATC. In addition, under specific conditions, aircraft are able to be dispatched for short periods of time without a serviceable TCAS.

Additional information

In high reliability systems, there are multiple risk controls in place to reduce the likelihood that safety-critical personnel will make an error. However, on rare occasions an error will still occur, and systems have additional risk controls in place to detect and recover from such errors, or mitigate the consequences of such errors. In this occurrence, one of these detection and recovery controls did not work effectively (that is, the TCAS on EBO). However, other risk controls were functioning effectively. These included the ATC STCA, EBS’s TCAS, and the use of one-way routes.

Further investigation

The investigation is continuing and will include:

- further analysis of the ATC radar and audio data and the recorded data from the two aircraft

- analysis of the context in which the controller’s actions occurred

- examination of the TCAS computer and related components from VH-EBO

- review of the reliability and availability rates of TCAS.

Purpose of safety investigations

The objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

- identifying safety issues and facilitating safety action to address those issues

- providing information about occurrences and their associated safety factors to facilitate learning within the transport industry.

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action.

Terminology

An explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue.

Publishing information

Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003

Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau

© Commonwealth of Australia 2013

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication

Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia.

Creative Commons licence

With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence.

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work.

The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau

Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly.

|

_________

1 Controlled aircraft should be kept apart by at least a defined separation standard. If the relevant separation standard is infringed, this constitutes a loss of separation (LOS).

2 Eastern Standard Time (EST) was Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 10 hours.

3 At altitudes above 10,000 ft in Australia, an aircraft’s height above mean sea level is referred to as a flight level (FL). FL 390 equates to 39,000 ft.

4 Loss of separation assurance describes a situation where a separation standard existed but planned separation was not provided or separation was inappropriately or inadequately planned.

5 Traffic Collision Avoidance System Traffic Advisory, when a TA is issued, pilots are instructed to initiate a visual search for the traffic causing the TA.

6 Traffic collision avoidance system (TCAS) is an aircraft collision avoidance system. It monitors the airspace around an aircraft for other aircraft equipped with a corresponding active transponder and gives warning of possible collision risks.

7 Traffic Collision Avoidance System Resolution Advisory, when an RA is issued pilots are expected to respond immediately to the RA unless doing so would jeopardise the safe operation of the flight.

8 A minimum equipment list (MEL) is a list which provides the operation of aircraft, subject to specified conditions, with particular equipment inoperative.

________________

The information contained in this web update is released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 and is derived from the initial investigation of the occurrence. Readers are cautioned that new evidence will become available as the investigation progresses that will enhance the ATSB's understanding of the accident as outlined in this web update. As such, no analysis or findings are included in this update.